Layered Video Coding and Physical Layer Pipes: Engineering the Optimal Match for Next-Generation Broadcast Architecture

Broadcasters have a unique opportunity to satisfy consumers’ desire for the highest possible visual quality while continuing to uphold the public service mission of universal accessibility

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Introduction: When Video Compression Meets Physical Layer Innovation

As consumer television sizes continue to expand toward 100 inches and beyond, the demand for improved video experiences that fully showcase the capabilities of modern displays is also increased. Viewers expect images that are crisp, immersive, and lifelike, qualities that go well beyond what legacy High Definition (HD) broadcasting was designed to deliver.

Broadcasters have a unique opportunity to meet this growing expectation by offering cinema-grade Ultra High Definition (UHD) content enhanced with High Dynamic Range (HDR), wide color gamut (WCG), and high frame rates (HFR). Importantly, they can satisfy consumers’ desire for the highest possible visual quality while continuing to uphold the public service mission of universal accessibility.

The convergence of layered video coding and flexible physical-layer design represents a major architectural advance in this direction. Historically, video compression (codec design) and radio transmission (physical layer configuration) were treated as largely independent domains. This separation often forced broadcasters to adopt a single technical compromise, leaving users at the extremes, those with poor reception and those with premium displays, underserved.

Modern standards, however, such as ATSC 3.0 (NextGen TV), blur this separation. The physical layer now permits independently configured Physical Layer Pipes (PLPs), while advanced codecs like Versatile Video Coding (VVC / H.266) are designed to support native scalable bitstreams. When engineered properly, these two domains create emergent capabilities that neither can deliver alone: graceful degradation across receiver conditions, simultaneous baseline universality and premium peak quality, and spectrum-efficient delivery without requiring for simulcast.

Why the Pairing Matters: Addressing Heterogeneity

Both layered codecs and PLP-style physical layers are different technical answers to the same practical problem: how to deliver the best possible user experience across highly heterogeneous receivers and propagation environments. Video codecs must accommodate varying display sizes, decoder complexity, and available throughput; physical layers must accommodate variable propagation, antenna gains, and receiver sensitivity.

Layered architectures allow broadcasters to stop choosing a single, one-size-fits-all compromise and instead deliver differentiated service tiers simultaneously, allowing each receiver to extract the best representation its device capabilities and reception conditions can reliably support.

Understanding Layered Video Coding: From Monolithic to Modular Bitstreams

Traditional broadcast encoders produce a monolithic bitstream: every coded bit contributes to a single target representation, and losing a critical portion of that stream often renders the entire picture unusable. This all-or-nothing behavior is poorly matched to wireless broadcast, where signal quality varies continuously across time and geography.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

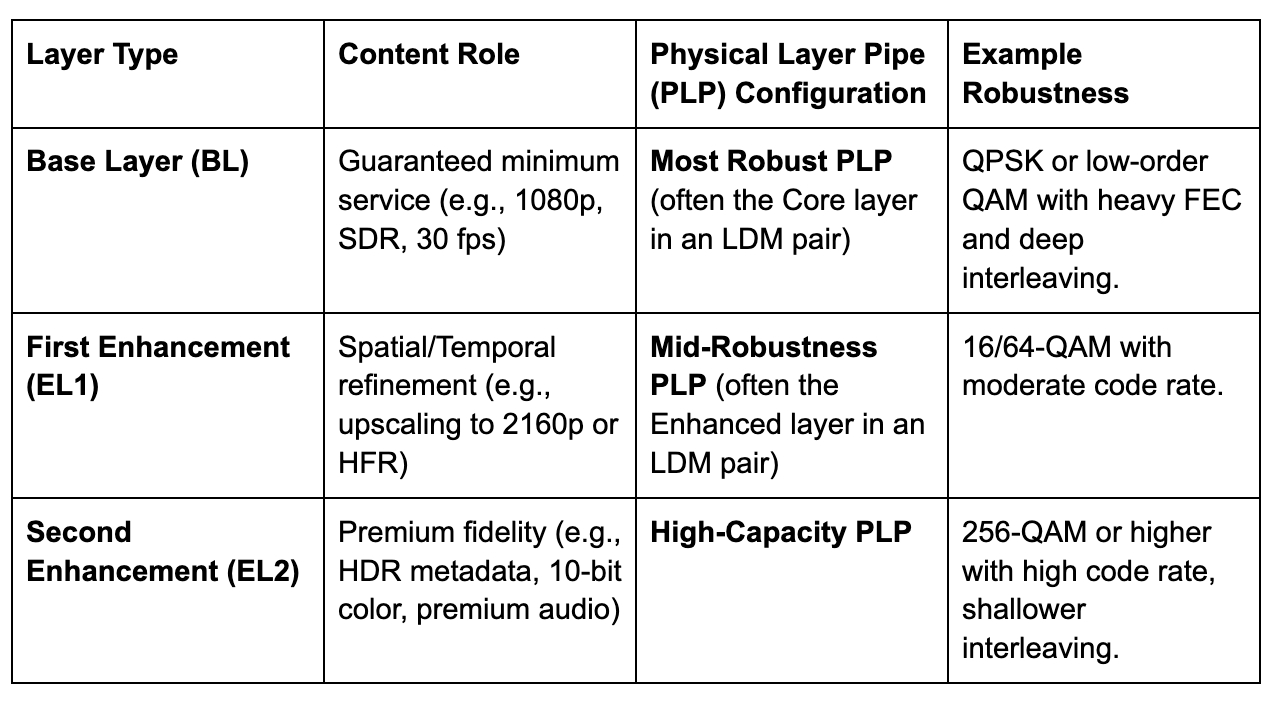

Layered (scalable) video coding restructures encoded data into a hierarchy of dependencies. A Base Layer (BL) is a complete, independently decodable representation, guaranteeing a minimum service level. One or more Enhancement Layers (ELs) then refine attributes such as spatial resolution, temporal resolution, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)/quality, or color/HDR characteristics.

Enhancement layers depend on lower layers, but lower layers do not require the enhancements. A decoder that receives only the base layer presents a complete, usable picture; a decoder that receives additional layers improves quality accordingly. VVC formalizes these capabilities, enabling spatial, temporal, SNR (quality), and color/HDR scalability. The VVC standard was finalized in July 2020, and its constraints for use in ATSC 3.0 are defined in the ATSC A/345 standard [1].

Physical Layer Pipes: Parallel Channels with Tunable Robustness

ATSC 3.0’s OFDM-based physical layer departs from the single-mode approach of legacy systems by enabling multiple PLPs inside one RF channel. Each PLP is an independently parameterized logical channel: modulation order (e.g., QPSK, 256-QAM), Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) code rate, interleaver depth, and pilot density are chosen per-PLP to define its robustness.

The combination of layered video coding (VVC) and ATSC 3.0 Physical Layer Pipes represents a strong architectural alignment that directly addresses the fundamental challenge of broadcast heterogeneity.

The transmitter multiplexes these PLPs into a single OFDM waveform. Receivers attempt demodulation of each PLP independently and decode whichever PLPs their instantaneous SNR permits. Because all PLPs are present on the air simultaneously, a receiver never "requests" a PLP, it simply demodulates those PLPs for which its link budget and channel conditions meet the configured thresholds.

A feature that complements PLPs is Layered Division Multiplexing (LDM). While PLPs can be multiplexed using Time or Frequency Division Multiplexing (TDM/FDM), LDM allows two PLPs (a Core and an Enhanced layer) to be transmitted on the same frequency and time, but at different power levels. This provides a significant SNR gain (typically 3–9 dB) for the Core layer, ensuring extremely robust reception for the base service in challenging environments like deep indoors or mobile scenarios [2].

Architectural Synthesis: Mapping Layers to Pipes

When scalable VVC bitstreams are mapped onto PLPs, two hierarchies align: content importance (base vs. enhancement) and transmission robustness (robust PLP → less robust PLP). The canonical mapping is a direct alignment of these two concepts, often leveraging LDM for the most critical base layer.

A receiver in a premium reception area demodulates all PLPs and recombines them into the highest quality picture. A receiver in a moderate area may demodulate the first two PLPs. Crucially, a receiver in a challenging indoor or mobile environment decodes only the robust base PLP and still presents a complete, usable picture. The broadcaster transmits all PLPs in the same RF band simultaneously; there is no per-receiver negotiation or dynamic retransmission.

Spectrum Efficiency: Why Layered Transmission Beats Simulcast

The primary operational and technical benefit of this synthesis is spectrum efficiency without the need for simulcast. In legacy practice, serving multiple quality tiers required broadcasters to either:

- Simulcast separate complete streams (e.g., one SD stream plus one HD stream), which multiplies the per-service payload and wastes capacity by repeatedly carrying overlapping content.

- Select a single operating point, which simplified operations but inevitably left many receivers either underserved or provided unnecessarily robust transmission for everyone.

Layered coding combined with PLPs replaces simulcast by partitioning a single content representation into a compact base layer plus incremental enhancement layers. The base layer contains the essential information necessary for a universal service; enhancement layers carry only the delta information needed for higher fidelity. Because the enhancement layers are incremental, the total transmitted payload to deliver multi-tier service is substantially lower than the sum of separate simulcast streams that would be required to offer the same service tiers.

The efficiency gain comes from data-level sharing (the base + deltas) rather than repeating complete representations. For example, transmitting a base 1080p stream plus a delta that upgrades to 2160p requires far fewer extra bits than transmitting two independent full-rate 1080p and 2160p streams. This reduction in redundant payload across quality tiers is the practical source of spectrum efficiency in layered broadcast workflows.

Technical Deep Dive: Synchronization and Dependency Management

Successful deployment requires careful alignment across codec packetization, IP transport, and PLP signaling:

- Codec/Packet Alignment: The VVC encoder must produce Network Abstraction Layer (NAL) units and layer boundaries that can be mapped into PLP packet payloads so that each PLP carries complete, independently decodable units for its assigned layer(s).

- Transport and Multiplexing: ATSC 3.0’s IP-centric transport (ROUTE/DASH/MMTP) carries PLP payloads. The Service Layer Signaling (SLS/LLS) informs receivers which PLPs map to which service layers and, critically, the dependency structure. Receivers must know that PLP-1 enhances the service in PLP-0 rather than representing an independent service.

- Timing and Buffering: The base layer must be presented on time even when enhancement data arrives late or intermittently. This implies specific encoder choices (e.g., BL frame lead time) and receiver buffer policies to permit enhancement merging without causing playback stalls.

Conclusion: A Genuinely Transformative Synthesis

The combination of layered video coding (VVC) and ATSC 3.0 Physical Layer Pipes represents a strong architectural alignment that directly addresses the fundamental challenge of broadcast heterogeneity. The primary operational and technical benefit, spectrum efficiency without simulcast, derives from transmitting a single layered representation (a shared base layer with incremental enhancement layers) rather than multiple independent streams.

Receivers decode the PLPs their channel conditions support, enabling graceful service adaptation across diverse reception environments. When intentionally engineered and deployed, this synthesis is positioned to deliver broader baseline coverage, significantly improved indoor and mobile performance (particularly when leveraging LDM), and premium UHD/HDR experiences for high-SNR receivers - all within a single, highly efficient RF transmission.

References[1] ATSC. ATSC Standard: VVC Video (A/345). Advanced Television Systems Committee, 2025. [2] ATSC. ATSC Standard: Physical Layer Protocol (A/322). Advanced Television Systems Committee, 2021.

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Row 0 - Cell 1 | Row 0 - Cell 2 |

| Row 1 - Cell 0 | Row 1 - Cell 1 | Row 1 - Cell 2 |

| Row 2 - Cell 0 | Row 2 - Cell 1 | Row 2 - Cell 2 |

Ling Ling Sun is Vice President of Technology for Maryland Public Television and former CTO at Nebraska Public Media from 2014 to 2025.

A respected industry leader, Sun serves as a director on the ATSC Board and is an active member of the NAB Television Technology Committee. Her commitment to public broadcasting is evidenced by her two consecutive terms chairing the PBS Engineering Technology Advisory Committee (ETAC) from 2013 to 2018, alongside her service on the PBS Interconnection Committee. Sun further demonstrated her leadership by heading the NAB Broadcast Engineering & Information Technology (BEIT) Conference Program Committee in both 2023 and 2024. Additionally, she has contributed her expertise to the Technical Panel of the Nebraska Information Technology Commission.