The History of ENG, Part 4: Ergonomics and The Elements

As with most nascent industries and endeavors, movement into ENG was not painless, bringing along new problems and issues for early adopters

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This is the fourth installment in a multi-part series by broadcast historian and former TV Tech Technology Editor James O'Neal.

As documented in the previous installment of this lookback at electronic newsgathering’s development, the era of “modern” ENG came about in the mid-1970s, as a “perfect storm” in technology finally enabled broadcasters to move away from movie film for capturing out-of-studio news events and into electronic imaging and recording.

After the initial pieces — smaller, lighter-weight color cameras and videotape recorders, along with editing systems that accommodated this new media —began to fall into place, broadcasters started to dip their collective toes in the water, with some embracing the technological shift wholeheartedly and others holding back for one reason or another. However, the ENG movement had begun and it was inevitable that film’s days were numbered.

As with most nascent industries and endeavors, movement into ENG was not painless, bringing along new problems and issues for early adopters. One of these, described in the previous ENG history installment, involved operators at full-service filling stations assuming that van camera or cable ports were gas tank filler openings and inadvertently flooding a vehicle with gasoline. Other issues were more subtle and didn’t involve third parties.

Powering First Gen ENG Gear Was Not Always Easy

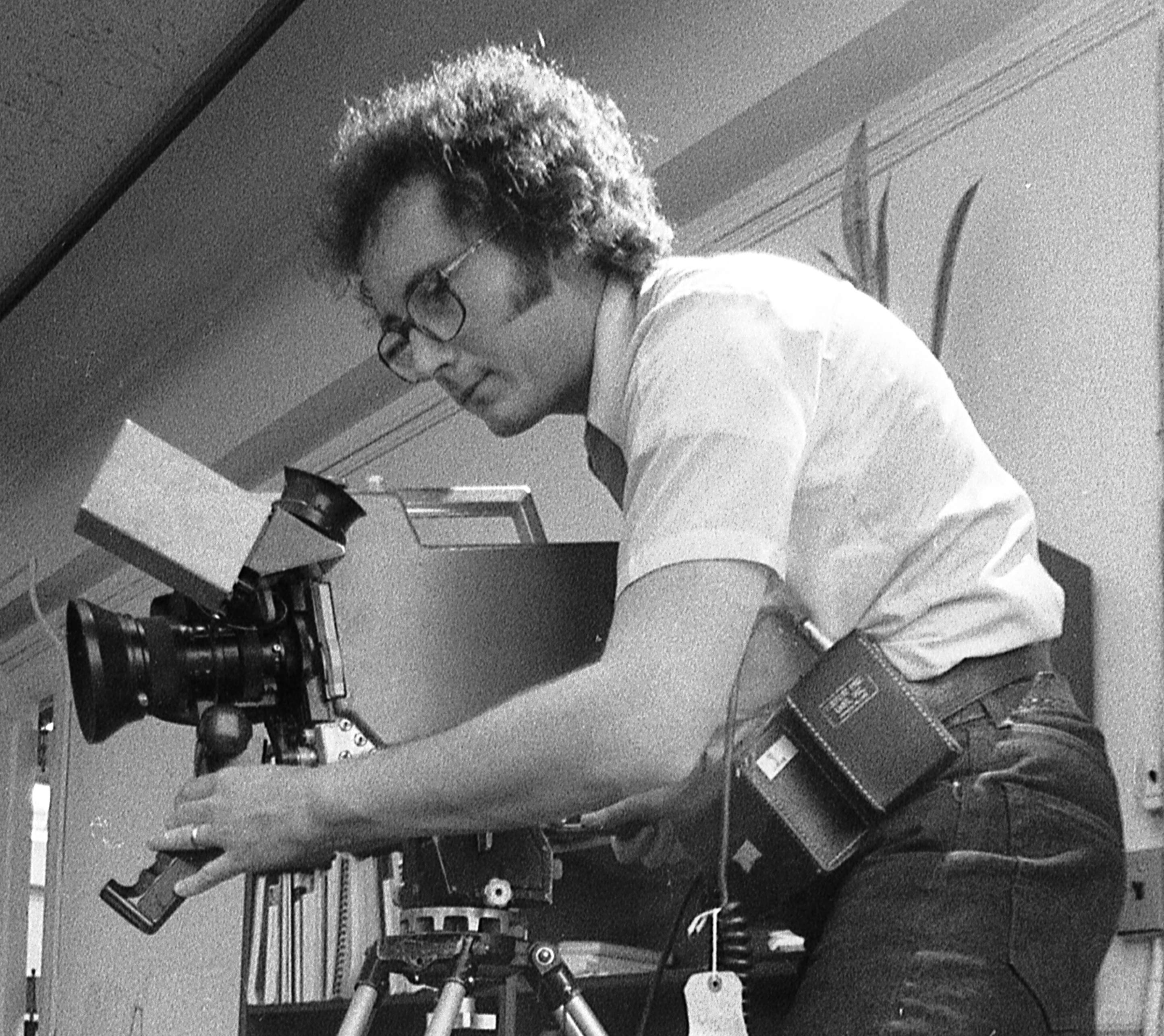

Portable television cameras continued to shrink both in bulk and weight. Imager sensitivity, or the ability to produce satisfactory images in low-light situations, also became a driving force in R&D groups, as did reductions in electrical power requirements.

Power demands of most all of the early ENG cameras were so great that operators wore “belts” with compartments for a sufficient number of rather heavy “NiCad” (nickel-cadmium) batteries to accommodate anticipated shooting times. According to Jay Ballard, who was with NBC when the 1970s ENG movement began, power requirements for some of the early cameras made battery packs even more cumbersome.

“The first cameras used at NBC’s Washington O&O, WRC-TV, were Norelco PCP-90s,” Ballard recalled. “They were paired with Ampex VR-3000 two-inch quad backpack video recorders. (Both) had substantial power requirements.”

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

He noted that the NiCads powering most early ENG gear could be problematic. One issue was a “memory” effect, with batteries that were not fully discharged before recharging developing substantially shorter operating times. Another issue was the tendency of fully-charged NiCads to self-discharge on their own, creating unpredictable results when an ENG shoot was underway.

“Battery life was always an issue,” noted Ballard. “We used batteries from a number of manufacturers along with special charging (equipment) to try and overcome this problem.”

George Lemaster, who was also with NBC during ENG’s initial rollout also recalled the demands on the operation’s engineering department in terms of battery maintenance.

“NBC Washington deployed more than 20 ENG crews and there was one technician whose duties centered on maintenance of the large number of batteries being used,” he said. “These were NiCads and also some very expensive silver zinc that required a special charger.”

Lemaster amplified Ballard’s NiCad observations.

“Some would last a long time and some wouldn’t. It was the job of the battery technician to determine the run time of each of the battery packs in use. He would discharge them using a timer to see how long they lasted. NBC practice was just to trash a sub-par NiCad pack,” he said. “These were made up of several ‘D’ cells, and usually only one these had failed by shorting out, but that meant the rest were very near end of life.

Those involved in early ENG also recall the heavy and uncomfortable “battery belts,” which completely encircled the camera operator’s mid-section and contained multiple pouches for the batteries needed to power both the ENG camera and the equally power-hungry portable lighting instruments necessary to produce airable video in many low-light situations.

Art Donahue, who shot news and documentary footage for a number of New England stations, remembered some of his own experiences with battery belts.

“In cold weather, you usually needed multiple battery belts to get through a shoot,” he recalled. “The cold weather affected battery output and you would have to carry the extra belts under your parka to keep them warm.

Donahue also recalled another issue that existed before batteries were integrated within camera and recorder housings.

“The connecting cables were always a problem. They kept getting pulled out and frequently failed,” he said. “We had to kept plenty of spares.”

Those Problematic Masts

Microwave antennas used on the early ENG vehicles had very simple pan-and-tilt mounts, with the dish only a few feet above the top of the van or truck. While such mounts were satisfactory when beaming signals to a communications tower or high-rise receiving/relay site, their low elevation above ground was a limiting factor in getting video back to the TV station.

It wasn’t long in the evolution of ENG that some stations began to experiment with telescoping pipe masts in an effort to elevate van transmitting antennas. Later, a commercial product using compressed air as a means for raising the pipe sections was developed and soon became standard equipment on all ENG vehicles.

While these pneumatically-driven telescoping masts did provide greatly enhanced coverage range, they came with their own set of issues. One of the worst usually happened when a crew was in a hurry to go live with a breaking news event and the vehicle operator inadvertently parking under powerlines and elevating the mast without checking for obstructions.

This sometimes-lethal occurrence was eventually remedied via a sensor for nearby AC powerline fields and an interlock that would not allow extension of masts if a power line hazard existed.

Another issue was the occasional “stuck” mast, that typically happened in cold weather.

As explained by Bob Russo, former chief engineer at New Haven’s WTHN, this was due to freezing of water vapor in the compressed air supply used to drive the mast extension.

“This was something we always faced during cold weather,” said Russo. “The moisture in the compressed air would freeze the O-rings used to provide an air seal around each of the pipe sections. We tried any number of things to keep moisture out of the air supply, but every so often the O-rings would freeze and keep the operator from lowering the mast after the news feed.”

Russo explained that the remedy for such freeze-ups was to unbolt the collars at the top of the mast sections, starting with the one closest to the truck. He recalled one rather catastrophic situation involving a stuck mast on the station’s ENG truck that occurred when the operator either misunderstood or didn’t follow the procedure supplied by the station’s chief of maintenance.

“This was in January,” recalled Russo. “There was a really awful accident involving a line of cars stopped and waiting to pay tolls when they were hit by a tractor-trailer rig. We were on the scene for live coverage, and when this wrapped up, the van operator found that he couldn’t get the mast to lower and called in to speak with the maintenance chief for instructions on freeing the stuck mast. This called for loosening the U-bolts on the collars on each of the sections.

“Apparently the operator misunderstood his instructions and applied air pressure after loosening the first collar. The result was the launch of the eight-section 42-foot mast and microwave antenna. When it came down it fell across the highway, fortunately, it came down clear of the stopped cars, otherwise, there could have been additional casualties that night.”

Russo also recalled van operators sometimes overriding interlocks that prevented van movement when the mast was deployed.

“They would be in a hurry to get a better microwave shot back to the station and decide to move the van a few feet without lowering the antenna. We had one incident where this resulted in damage from the mast hitting a tree limb.”

Living With 'Plastic Faces'

Early ENG adopters recall another issue associated with conversion from film to tape operations that no amount of operator training or change in workflow practices could alter. This was a rather peculiar "look" associated with news events captured on small-format videotape machines. In order to shrink the profile, weight, and power requirements of videotape recorders, sacrifices in performance had to be made. The greatest of these was reduction in video bandwidth.

“I evaluated small format machines for video and chroma response,” Ballard recalled. “The video they produced was nowhere near what a conventional ‘quad’ broadcast machine produces.”

The problem stemmed from lower head-to-tape “writing speeds” that were necessary to allow video recording on small and easily handled magnetic tape media. It should be recalled too, that the 3/4-inch Sony U-matic cassette tape format—which became an early ENG industry standard—was never intended for broadcast purposes, but rather for educational and institutional applications where size, convenience and ease of use trumped video performance. The author once measured video frequency response of a new U-matic machine and observed that there was little above 2.25 MHz.

Obviously, NTSC color video, with its chroma information centered around a 3.58 MHz carrier, could not be captured by the U-matic or any of the other first generation of small portable video recorders, so some electronic trickery had to be employed. As explained by Ballard, this involved some electronic alterations.

“Although Sony may have been the first manufacturer to employ it in video recorders, the principle of ‘color under’ came from RCA back in the 1950s,” he said, explaining that when NTSC color was introduced in late 1953, a number of television stations received their network feeds via AT&T Long Lines “L1” coaxial cable paths that dated back to the early 1940s. These coaxial cable routes were designed basically to accommodate multiple voice telephone circuits, with the technology leading to them going back to the 1930s when video was still in its infancy.

As such, L1 frequency response was limited to somewhat less than 3 MHz. To transmit color, RCA devised a scheme for bandpass filtering of the 3.58 MHz chroma content, then filtering the luminance component so that it did not exceed 2.0 MHz. The chroma content was heterodyned down in frequency and transmitted slightly above the bandwidth-limited luminance.

When the modified NTSC color signal was delivered to a TV station, the process was reversed, with the chroma being converted back to its 3.58 MHz berth and recombined with the luminance component. While it wasn’t the best looking video, the process did allow stations to broadcast network color until AT&T could improve their delivery system.

A similar scheme was employed to accommodate color in early small-format video recorders.

“This was okay with one generation of video recording,” said Ballard. “The problem arose when you started editing these tapes.”

NBC did have a rule of thumb that any videotape format used had to hold up for at least three generations.

Jay Ballard

Such editing necessitated re-recording the already bandwidth-compromised video, especially the chroma information. After just three generations, surviving detail in the colored areas was limited to no more than a few tens of kilohertz. This lack of detail was especially noticeable in human faces, with the effect being dubbed “plastic faces.”

“This is what happens when you try to squeeze in too much information into limited bandwidth,” said Ballard, “With ‘quad’ and (later) “type C,’ you didn’t have this color problem, as these formats were designed for broadcast.”

While "plastic faces" were never an issue when news capture was done on 16mm color film, it became something of an early ENG trademark, with the immediacy afforded by use of small-format videotape recording generally overriding quality concerns both at network and local TV station levels.

“NBC did have a rule of thumb that any videotape format used had to hold up for at least three generations,” recalled Ballard. “But this was very loose.”

The adoption of video recorders not really intended for broadcast use also created another issue; one that was not so apparent as plastic faces.

‘A Little Extra Blanking Never Hurt Anyone'

The airing of recordings made on so-called “slant-track” VTRs, especially those employing the 3/4-inch “U-matic” format, came with a defect of sorts that the developers of the earlier quadruplex broadcast format machines had been mindful of, and took measures to conceal.

This was the slight perturbation in recovered video that existed when one video playback head ended reading a recorded video track and another head began to scan the next track. The smaller slant track VTRs adopted for ENG were designed with two heads on a common drum, with each recording (or playing back) a complete field (262.5-lines) of video.

On playback, as one head completed its scan of a video track, it was switched off and the second head became active. This resulted in a small amount of visible “flutter,” sometimes referred to as “flag waving” in the recovered video. Sony and other manufacturers designed their machines to place this switching near the bottom of the frame, just above the vertical blanking interval (VBI) where it was less noticeable.

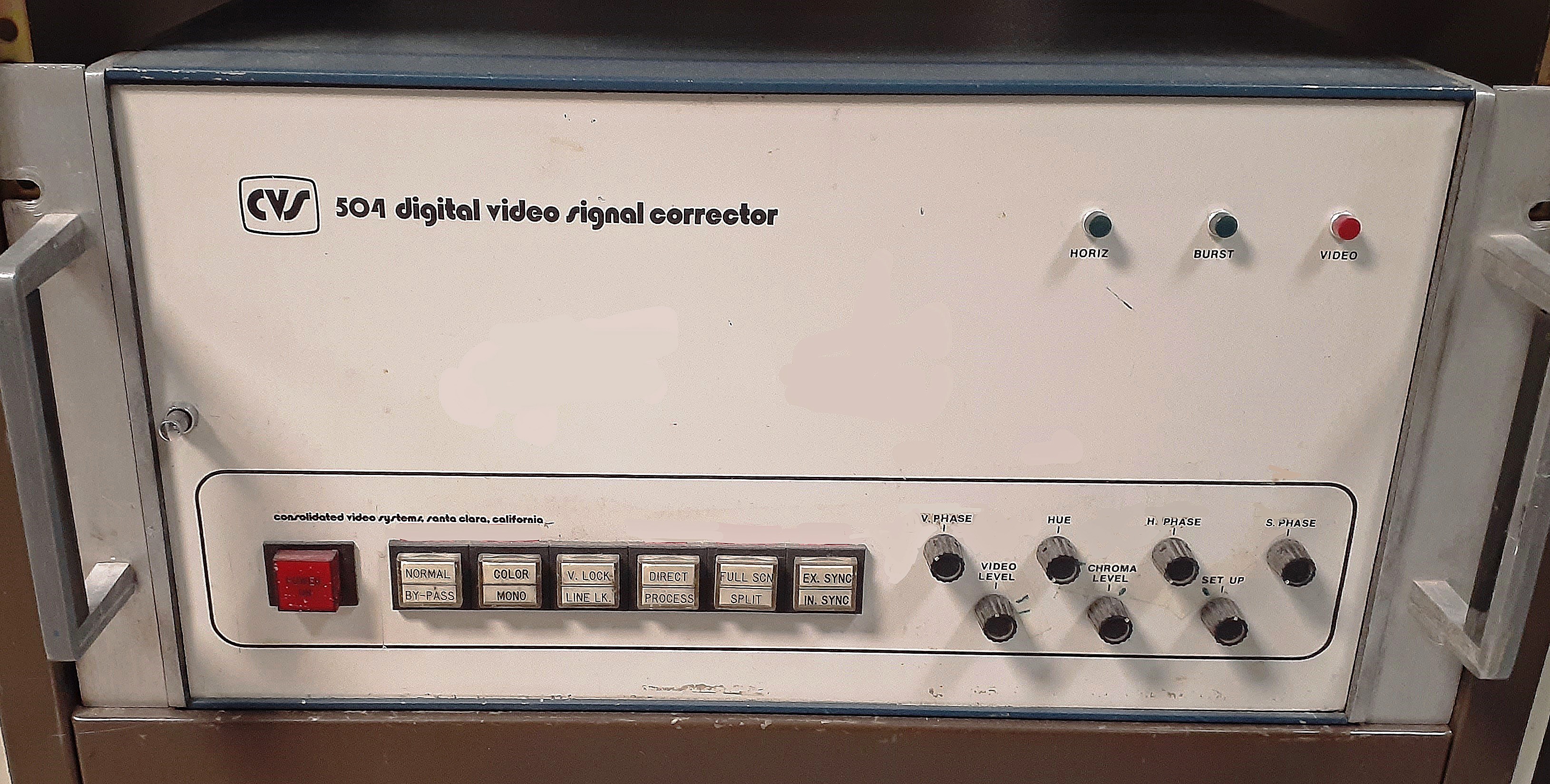

As explained by George Lemaster, a problem arose when some broadcasters wanted to hide this disturbance, in connection with external time base correctors (TBCs) used to provide “legal” sync and blanking signals from the VTRs.

“The CVS 504 (a very popular early TBC) had a ‘vertical advance’ control,” said Lemaster. “Broadcasters would use this control to shift switching out of bottom of picture, and this increased vertical blanking beyond 21 lines.”

The reasoning was that a few extra lines of black in the picture didn’t matter that much. However, at about the same time as the ENG movement was sweeping through the industry, the VBI was beginning to get a lot of attention with the arrival of vertical interval test and reference signals, as well as space for accommodating ancillary data delivery services (Teletext and closed captioning).

An FCC field inspector really didn’t need specialized test equipment to spot stations with excessively wide VBIs. All it took was a quick look at a TV monitor or receiver. Within a four-year period (1974 to 1978), the Commission had issued nearly 250 citations. And as Broadcasting magazine reported, it wasn’t “mostly the little guys” who were being cited. A number of major market stations, including network O&Os, had been ticketed.

“I do recall the FCC handing out citations,” said Lemaster. “NBC came out with a set of standards to comply with FCC rules. We had to go through all of our tape machines and set blanking widths to make sure they were correct.

“Back then, you could also misadjust cameras to produce excessive blanking widths,” he said, noting that the airing of recordings produced by out of tolerance cameras could result in non-compliance with FCC rules.

“NBC would reject tapes (from outside sources) with blanking widths that were too wide.”

By June 1978, the blanking situation had gotten serious enough to prompt the FCC to issue a Notice of Inquiry to determine if changes needed to be made to Commission regulations governing television waveforms, and setting a one-year grace period that allowed blanking widths to slightly exceed specs.

An industry group — the Broadcasters Ad Hoc Committee on Television Blanking Widths — was also created with the objective of helping to “identify problem areas and recommend corrective action” to the FCC.

Eventually, blanking discrepancies were resolved through greater operator vigilance, along with the development of technology for easily spotting and correcting signal issues.

(The next installment of this ENG history series will examine the addition of communications satellite technology as a news gathering tool.)