The History of ENG, Part 5: Satellite Enters the Picture

Sometimes the shortest path back to the station is 44,472 miles long

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This is the fifth installment in a multi-part series by broadcast historian and former TV Tech Technology Editor James O'Neal.

By the late 1970s, electronic news gathering was in use at almost every U.S. television market, large or small, with film coverage of events rapidly becoming a fond—or perhaps not-so-fond—memory. ENG had proven itself to be an absolutely essential part of television news operations.

LIive News Feeds Could Sometimes Be Problematic

However, as accepted and indispensable as it proved itself to be, ENG did have a fundamental limitation when it came to live coverage of breaking events — there had to be a clear microwave path from a station’s ENG truck back to its receive site. This “line-of-site” limitation was especially problematic in large cities with tall buildings, and in other areas where terrain and geographic features could block signals. And as more and more stations (and television networks) adopted ENG, another issue arose — spectrum congestion.

Even in areas with relatively few TV stations, filing fast-breaking or even routine stories could sometimes be challenging.

Bob Russo, who was with New Haven, Conn.’s WTNH when that station first implemented ENG, recalled that “with only seven microwave channels available in Connecticut, this created a problem at times.” Russo noted that in setting up for ENG operations, WTNH established two microwave receive sites, which, due to the relative flatness and small size of Connecticut, provided coverage from a lot of sites within the state.

“One of our sites was at our transmitter in Hamden, north of downtown New Haven,” said Russo. “The antenna was mounted on our tower, 840-feet up. The other site was in Hartford (about 35 miles distant) atop a bank building. Each had four Nurad horn antennas that could be switched remotely. With double-hopping, we could hit a great deal of the state. However, there are some valley areas that made things difficult.”

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

ENG microwave connectivity issues were not limited to areas with deep valleys, tall mountains and high buildings. Even in very flat and open areas of the United States, microwaving news stories back to home base could be problematic. As recalled by Roger Herring, who was with Tulsa’s KTUL-TV in the early days of ENG, getting signals across the great open plains of Oklahoma could also be daunting.

“A lot of time there were events that affected us in Tulsa that took place in the capital, Oklahoma City,” said Herring. “Microwave at that distance (about 100 miles) wasn’t always possible, even with relatively high antenna locations. This limited our ability to cover events from just anywhere in Oklahoma (an area of almost 70,000 square miles).

(The Tulsa television market also extended into the neighboring states of Kansas, Arkansas and Missouri, with the Ozark Mountains to the east of Tulsa further limiting ENG microwave connectivity.)

Satellite Video Linkage Comes of Age

Concurrent with ENG boom period in the latter part of the 1970s, a solution to both the terrestrial blockage and transmission channels was also emerging — an increasing interest in use of communications satellites for relaying television signals. Although video had been relayed via satellite as early as 1962, use of this technology had been very limited due to high costs, and the large physical size of transmitting and receiving antennas (10-meters (33-feet) or more).

Further, the susceptibility of weak satellite downlink signals to terrestrial microwave interference generally required earth stations to be located well away from cities, with connectivity to users provided by common carrier microwave and coaxial cable runs. Early on, this restricted satellite use to major networks, and mostly for well-planned coverage of predictable high-profile events such as the Olympic Games or the “splashdown” of early manned spacecraft.

However, this was eventually destined to change; initially from improvements in low-noise amplifiers and other technological advances, but much more profoundly with an Oct. 18, 1979 decision by the FCC to eliminate licensing of all earth stations, along with the expensive and time-consuming frequency coordination process necessary for establishing a satellite receiving facility. The commission further aided the satellite communications industry by dropping its previous mandate governing minimum size of satellite receiving antennas.

The Commission’s change in stance was universally heralded, with Broadcasting magazine opining:

“The FCC has opened the floodgate on receive-only earth stations — a development of almost revolutionary significance to radio, of great importance to television and, indeed, of signal significance to all telecommunications users, including newspapers.”

This decision was also destined to decrease the cost of entry into the satellite club, with manufacturers beginning to lower unit costs due to increased sales volumes and industry competition.

On learning of the FCC decision, Sid Topol, chairman of a major satellite equipment supplier, Scientific Atlanta, remarked that while his company’s earth station sales volume had reached hundreds of thousands of units, SA was willing “to take this to a volume in the millions.” Topol predicted the arrival of earth stations that could be erected in a single day and with nothing more than “a Boy Scout compass and a Hewlett Packard calculator,” providing every broadcaster with satellite reception capability.

Three Mile Island Spurs Connectivity Changes

Even before the loosening of earth station regulations, some broadcasters were already looking to the future and beginning to think about how satellite linkage might be useful in news operations, especially in the aftermath of a news event that generated banner headline around the globe.

This was the March 1979 incident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power station located near Harrisburg, Penn. that resulted in the melting of nuclear fuel and the potential for a widespread lease of radioactive material. News teams from major networks and independent operations alike converged on the scene (or as least as close as authorities would allow), solidly booking any available video connectivity.

Once the danger had passed, at least one broadcast group’s news coverage postmortem considered how its coverage of this unprecedented event might have been seriously impacted by lack of terrestrial video circuit availability. This was the Westinghouse Broadcasting (Group W) operation, which operated stations in several markets (Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh) fairly close to the power plant.

This potential, along with the rising cost of AT&T terrestrial video circuits and the public’s increasing appetite for news on the local/regional level prompted Westinghouse to contract with Western Union for regular transponder time on its Westar bird. Not only did this ensure a transmission path for moving stories from the field to Group W stations, it also permitted daily exchanges of news, features, and sports coverage among stations. Westinghouse also allowed stations outside of the Group W fold to subscribe to this newsfeed service.

While large dish sizes and the relative complexity of the C-band satellite uplink technology at the time precluded its application in bringing back “breaking news” from the field, the Westinghouse initiative did not go unnoticed by others.

NBC Establishes Viability of Ku-Band Spectrum

Another sign of satellite connectivity’s importance was also beginning to take shape at about this time — the replacement of terrestrial microwave and coaxial cable circuit (primarily AT&T Long Lines) with satellite paths for delivery of network programming to network affiliates. Although PBS had pioneered this movement in 1978, the big three commercial nets adopted a “wait and see” attitude, with concerns about moving to a delivery platform with a potential single point of failure, conversion costs, and the loss of the overall comfort level established after three decades of leaving program delivery to AT&T.

As expressed by CBS’s then vice president of operational resources, Frank Smith Jr., in a Broadcasting magazine interview:

"The systems we now have do the job on an economic basis that is acceptable to us."

However, ABC’s president of broadcast operations and engineering, Julius Barnathan, observed that his network was spending some $20 million per year on AT&T distribution charges, and seemed to be a bit more open to exploring satellite delivery.

"I'm willing to go another direction," said Barnathan, "but it's all (about) cost effectiveness" and reliability.

Despite these initial holdouts, it was only a matter of time before the commercial nets caved.

NBC went first, launching its Skypath satellite affiliate delivery in early 1984. The network’s decision to use a Ku-band transponder for this service was very significant in the path eventually leading to satellite newsgathering.

Prior to NBC’s Skypath, Ku-band satellite spectrum was generally viewed as less-than-desirable due to potential for rain fade and the requirement for very precise dish pointing.

However, a much smaller entity, St. Paul, Minn.-based Hubbard Broadcasting, had used the Ku-band to ease into the satellite communications, first in 1981 with a satellite-delivered direct-to-home TV service, and then with the realization that a Ku uplink could be fitted on a mobile platform, green-lighted construction in 1983 of the first-ever vehicle specifically designed for relaying live video news feeds.

Eyewitness to Tech History

Fred Baumgartner, a retired career broadcast engineer, recalls his inadvertent witnessing of the first use of the Hubbard SNG truck and the birth of satellite news gathering.

“This was in June 1984 and I was working at a Wisconsin radio station,” recalled Baumgartner. “There were some terrible storms passing through the area that Thursday evening, with the Madison (Wisc.) weather bureau issuing all sorts of severe weather warnings. In the wee small hours Friday — that would have been June eighth — a state trooper apparently out on routine patrol drove to Barneveld, a small community about 25 miles from Madison, and found nothing there but wreckage and a few dazed people wandering around. The whole town had literally vanished.”

The community had been in the direct path of an F5 tornado, with winds estimated to have been in excess of 300 mph. Baumgartner, an amateur radio operator, who, upon learning about the devastation, traveled to Barneveld to assist emergency responders with communications.

In addition to viewing a community that had literally ceased to exist, Baumgartner also discovered something he’d never seen before — a self-contained vehicle specially outfitted for uplinking video to satellites.

“The truck had just arrived from somewhere around the Chicago area,” he recalled. “I was curious, as I’d never heard of satellite news gathering. I met the operator, Ray Conover who was an engineer with the Hubbard stations, and learned that the truck was still being put together when he got orders to take it Barneveld. Ray was literally connecting gear up as it was being driven from Chicago. Although I didn’t realize it then, I would have to argue that this was first-ever SNG truck and the first use of this type of technology. “

Although Conover — known by many as “Dr. Dish” — passed from the scene several years ago, Baumgartner’s recollection of the June 8, 1984 event was borne out by Jay Adrick, who, a few months later got to do a close-up evaluation of the vehicle created by Conover.

“I believe that the first SNG vehicle was built by Hubbard,” said Adrick. “They did it on their own, building an early prototype somewhere around 1984.”

THE ROLLOUT OF SATELLITE NEWS GATHERING

Following an evaluation of the Hubbard prototype SNG truck, Adrick realized that there would likely be a market for such vehicles and as the company he had and others had established — Midwest Communications —was already constructing ENG trucks, it would be a logical next step to fill this anticipated demand.

Adrick admitted that the first Midwest SNG product, which appeared near the end of 1984 or in early 1985, was more or less a copy of the Hbbard truck, down to the 3.0-meter Andrew antenna selected by Conover.

“The Andrew dish was really designed for use in earth stations,” recalled Adrick. “It had plenty of elevation range, but was very limited in moving side-to-side, and at 3.0-meters, required a rather large truck frame to accommodate it.”

He explained that the only practical way to fit such an antenna into a mobile environment was to mount it in an open space at the very rear of the truck.

“These first SNG products were sometimes referred to as ‘garbage trucks’ due to their open back end and similarity to vehicles used for refuse collection.”

Despite the high price tag of the Midwest SNG vehicles — ranging from around $300k for a “bare bones” setup to $400k for a completely equipped unit ($900k to $1.1 million in today’s money) — Midwest did a brisk business, with CNN becoming one of its first SNG customers.

“This was not long after we’d completed our prototype truck, and followed a big train derailment in northern Ohio,” recalled Joe Mack, former Midwest Communications systems sales manager. “We got a call from someone at CNN saying ‘we know you have this satellite truck, can you sell it to us?’”

Midwest gained a reputation for creating better and better satellite trucks through their creative engineering approach, becoming a leader in the field and selling hundreds of units.

“We didn’t want to be a ‘me too,’” said Adrick. “We did a lot of things that were proprietary as opposed to just going out and assembling,” noting that one of the first Midwest innovations involved the truck’s antenna system.

“The 3.0-meter Andrew dish required a good-sized truck and as we had a relationship with another antenna manufacturer, Vertex, we went to them (to see if an improvement could be made). Rex Vardeman there worked out a design for a 2.6-meter antenna with a laminated reflector, an offset Cassegrain feed, and a very substantial azimuth-over-elevation mount. This allowed us to go to a medium-sized truck chassis.

“Also, we realized that with Ku, you have some losses even with a short waveguide run. We went to Microwave Communications Lab (MCL) to develop a TWT amplifier, combiner and control system that could be mounted in a rack inside the truck directly under the antenna. This cut losses and still kept amplifier out of the weather.”

Adrick noted that Midwest added another (pre-GPS) innovation, the use of the terrestrial LORAN navigation system for establishing the truck’s geographical coordinates and making it easier to determine satellite antenna pointing.

“We supplied an automated antenna controller that used an internal LORAN receiver for truck location. This unit made by Research Concepts used a lookup table for all known satellites,” said Adrick, “You could pull up to a location and select the satellite you wanted to use. The controller would drive the azimuth and elevation motors, with the operator just doing a minor tweaking of the dish. It made manual acquisition a lot easier.”

Sharing With Others

In addition to allowing transmission of breaking news events from just about any location accessible by a motor vehicle, SNG also brought with it the advantage previously realized by the Group W stations in their early use of fixed location satellite ground stations, the ability to simultaneously provide feeds to multiple users.

“Satellite transmissions are advantageous as your feed is up on a bird and everyone can see it,” observed Leland Kesler, a retired satellite truck engineer who began his career in SNG in 1995. (Kesler also refers to himself as a “truck monkey.) “This made it easy to do pool feeds without a lot of complicated routing of signals on the ground.”

Herring, who was on the road a few years before Kesler, agreed.

“Early on, breaking news coverage for our station was the prime reason for acquiring a truck,” said Hering. “You wanted to be the first to get there and the first to get the story on the air. The truck gave us the ability to cover stories anywhere in the state without having to depend on the limited range of microwave. It also gave us the ability to go out of state and cover stories that were national or semi-national in scope. We were able to support news operations for other stations in our group. We’d tell them that we were going to put a story up on the bird and when it was available. We also did many stories that ABC used.”

Herring recalled that his station’s (KTUL’s) SNG truck was instrumental in the airing of initial reports on the bombing of the Alfred A. Murrah Building Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

“We fed our station, as well as other stations in the Allbritton group, he said. “And we also provided ABC with feeds until they could get their own truck in place.”

Live Video From Just About Anywhere

With the widespread adoption of Ku-band satellite news gathering following the inaugural Hubbard tornado coverage, the next logical step was to create a means for deliver news feeds without the necessity for driving long distances in specially equipped vehicles.

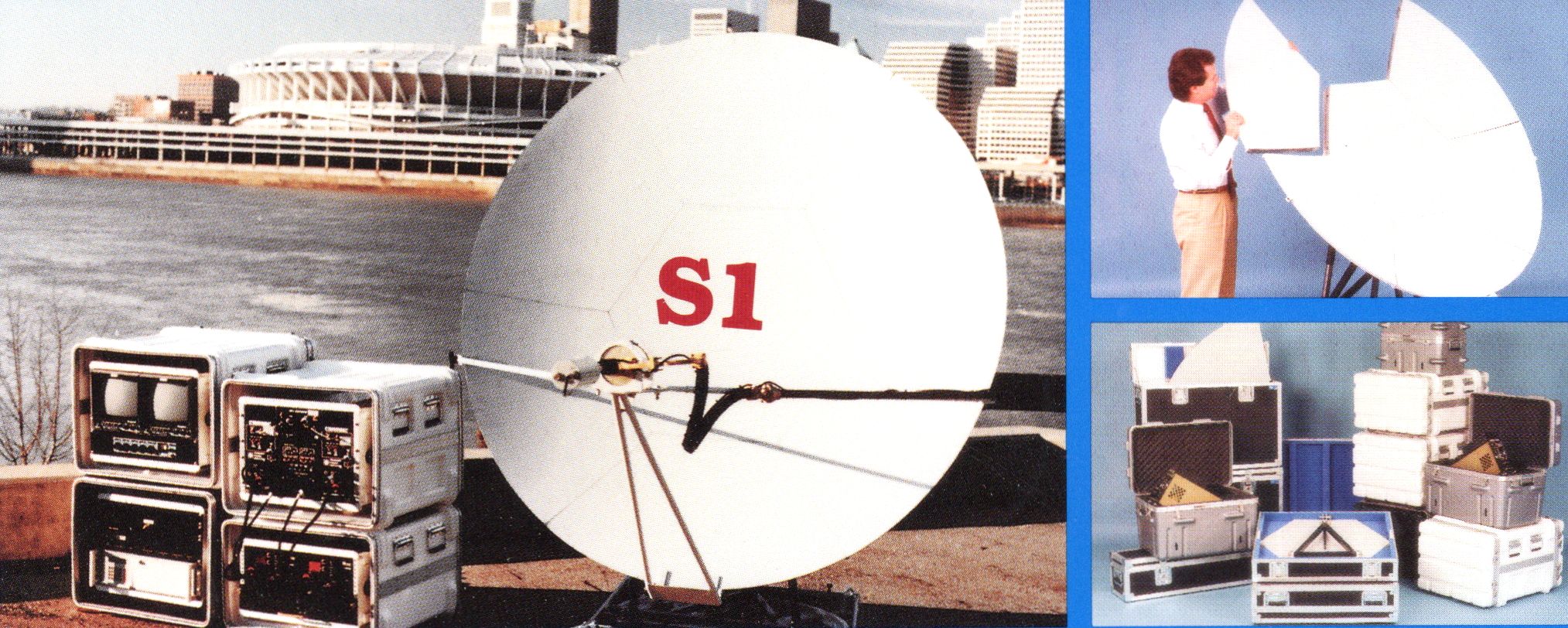

According to Midwest Communications’ Adrick and Mack, pioneering work on a “flyaway” travel case-based system began at their company.

“This was in 1986,” said Adrick. “CBS was interested in a flyaway type of uplink for use in covering the planned October summit conference between President Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that was going to take place in Reykjavik, Iceland.

“In developing this, we partnered again with Vertex to develop an antenna that could be disassembled into components small enough to be easily carried in field cases. They came up with a 1.8-meter dish with a hexagonal reflector hub and six panels that could be hemmed together to form the full reflector. Composite material was used for the reflector. It was two or three inches thick and could be stored in a single carry case. The Cassegrain feed horn and boom were transported in another case. A third case was used for the hub and antenna base.

“The next part was coming up with a compact portable amplifier. MCL didn’t have what we needed, so we turned to a New York company, Satellite Transmission Systems (STS), based in Hauppauge. They used a couple of TWT tubes along with a phase combiner and a pair of Varian power supplies and were able to get everything to fit in three component cases. Scientific Atlanta provided the exciter for the package. The rest of the equipment was simple — a 10 X 1 switcher, a monitor and an L-band receiver with a downconverter.

“The first of these flyaway units was delivered to CBS,” said Adrick. “Then CNN bought several more.”

Midwest’s Joe Mack recalled that part of the acceptance of the flyaway unit by CNN was being able to demonstrate that it would operate anywhere in the lower 48, as well as in Hawaii and Alaska.

“We had to make damn sure that it was operational in all parts of the U.S.,” recalled Mack. “We went around with a couple of CNN engineers to places like Brownsville, Texas and Florida, and all the way to Hawaii. The Hawaii test probably was the first use of a flyaway on an Intelsat hemispherical beam for delivery to CNN in Atlanta.”

Tony Williams, former director of engineering and operations at Atlanta’s Turner teleport, and someone who traveled extensively in connection with CNN coverage, recalled some of his experiences with the “suitcase” uplink developed by Midwest, especially its portability.

“The whole system typically went out in about 12 travel cases, with none of these weighing much over 100 pounds. They could travel on any airplane.”

Williams, in reflecting on his many uses of CNN’s flyaway equipment, observed that there would have been no live video coverage of the 1993 civil war U.S.-led UN Operation 'Restore Hope' in Somalia without the system.

“This was the most difficult deployment I was ever involved in,” said Williams. “It was a real nightmare. The military was set to make an amphibious landing and I was on the rooftop of an abandoned airport with Christiane Amanpour and three other network correspondents.”

Williams recalled that getting video back to CNN’s homebase in Atlanta was delayed due to a logistical issue.

“In traveling to Mogadishu, I stopped in London to pick up a flyaway pack that had been in Rome for some time,” he said. “It hadn’t been used for years, and when I finally got things assembled in Mogadishu I found that I couldn’t locate the satellite’s beacon with the spectrum monitor in the kit, and had to go out and locate a full-blown spectrum analyzer. It took six hours from start to finish before we were ready to go.

“We finally got on the air with Christiane reporting, and not long afterwards the amphibious assault started. This one was really crazy and dangerous. I remember asking myself: ‘you’re an engineer; what am I doing in a war zone?’”

Williams recalled that this delay came back to haunt him from a direction different than CNN management.

“About six months later, I was working at the Atlanta satellite uplink and my boss informed me that some DoD people wanted to talk to me. It seems that the military had wanted to see the CNN feed before they started their operations and I’d held up that deployment.”

In reflecting on ease of use, Williams admitted that deployment of a satellite truck would have almost always been faster in terms of getting on the air (“flyaways” typically took slightly more than an hour to unpack, assemble, power, and perform satellite coordination), the ability to get extremely close to a breaking news event just about anywhere on the planet made the travel case uplink an invaluable tool for news organizations.

“We were able to get to news scenes out in the middle of nowhere,” said Williams. “The flyaway was absolutely a gamechanger.”

(The next installment of this ENG history will examine the impact of digital technology on news gathering operations.)

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.