The Origins of Electronic Newsgathering

Tracing the beginnings of television news’ most essential ingredient

{Part one of a two-part series.]

The public’s interest in viewing distant “breaking news” events was stoked more than 100 years ago by the French Pathé motion picture company, with that organization producing and distributing the first “newsreels” to European movie houses in 1909 and in the United States two years later.

These short presentations of major news developments allowed audiences to experience such events in greater detail than the still images that appeared in newspapers and magazines. By the 1930s, a few specialty movie houses catered to serious “news junkies” by offering only newsreels running on a continuous basis, a precursor to the 24/7 schedule initiated by CNN in 1980.

Television news coverage, and the immediacy that comes with it, ultimately spelled the death knell of the theatrical newsreel, with the final installment coming from British Movietone News in May 1979 (U.S. newsreel production had ceased some 12 years earlier).

With this background, and the rise of numerous successful television entities that do nothing but broadcast news, it’s interesting to trace the evolution of “on the scene” television newsgathering and the technological developments that have now made it possible to capture and transmit live video from anywhere in the world.

Early Attempts

After a century, it’s sometimes a bit difficult to establish the true origin of many technologies and events—witness the competing claims for the invention of the telephone, radio, aviation and others. However, a very strong claim for priority in ENG exists for Schenectady, N.Y., TV station WRGB, which at the time of the history-making event operated under radio station WGY’s call sign.

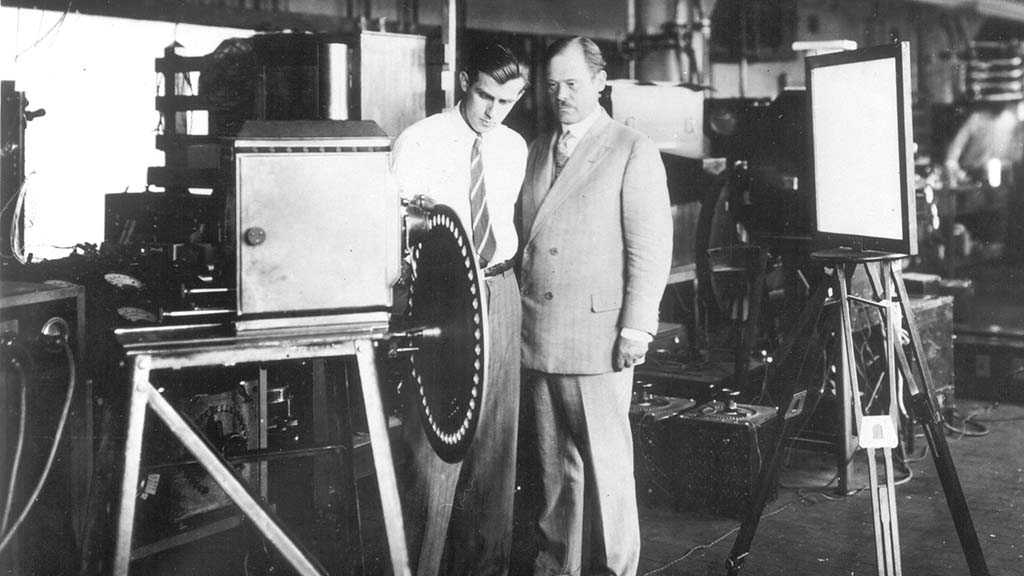

WGY was owned by General Electric, and its wizard of combined electrical and mechanical engineering, Ernst Alexanderson, had begun experimentation with television around 1926. He succeeded in developing a 48-line mechanical system, and with it, broadcast the first televised drama, “The Queen’s Messenger,” in September 1928.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Alexanderson had also devised a portable version of his equipment, and in the previous month transported it to the New York statehouse in Albany to televise Gov. Al Smith as he accepted his nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate on Aug. 22.

This first-ever bit of televised “breaking news” was reported to have been clearly received on the handful of television receivers that existed then. (Alexanderson later continued his television research independently of WGY, with the experimental call sign W2XCW. This pioneering station later became WRGB.)

Claims might be made by fledgling U.K. and German television operations in connection with the televised coverage of horse racing and the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympic Games, but these are better characterized as live coverage of sporting events, not breaking news.

A priority claim for the first electronically televised breaking event has to go to NBC and its 1939 experimental television station, W2XBS (later WNBT and now WNBC), which in November 1938 broadcast live the burning of an abandoned New York City building, and a few months later, covered the opening of the New York World’s Fair, with President Franklin Roosevelt, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and RCA President and CEO David Sarnoff all appearing before the camera.

ENG in the Postwar Television Boom

However, it was not until the end of World War II in 1945 that television began to be taken seriously by the general public and receivers started appearing in homes in substantial numbers. During this period, early TV broadcasters began to emulate their radio counterparts by increasingly taking programming out of the studio and into real-world environments, including live coverage of breaking news.

Credit for the first live coverage of a breaking “hard” story by television likely goes to Los Angeles station KTLA, which, not long after exchanging its experimental call sign W6XYZ for the commercial call, took its mobile setup to the scene of a massive explosion at a city electroplating plant. The Feb. 20, 1947, incident killed 17 people and damaged 11 nearby buildings beyond repair. KTLA microwaved video from the scene to its transmitter location atop Mount Wilson for retransmission to the few hundred TV sets then in use in Los Angeles.

KTLA also gets the honors for the first continuous television coverage of an evolving event—the attempted rescue of a 3-year-old girl who had fallen into an abandoned well. The station’s coverage of this 1949 event spanned nearly two days in April.

KTLA also wins—hands down—the honors for development and deployment in 1958 of the first helicopter television broadcasting platform, the “Telecopter,” which was the brainchild of the station’s chief engineer, John Silva.

Silva first experimented with a “tethered” configuration for video delivery, and with the success of this arrangement shifted to a “wireless” version, employing a special mobile microwave transmitter and non-directional antenna package built by General Electric.

The antenna was hinged so as not to impede helicopter landing operations, stowed horizontally until the aircraft was in flight. It was then dropped to a vertical position beneath the craft, radiating equally well in all directions. Signals could be easily tracked from an elevated receiving dish.

(As an historical note, Silva was not the first to transmit video from an aerial platform. Near the end of World War II, the military experimented with drone operation using early RCA camera gear, and in 1955, NBC used a Goodyear blimp to transmit portions of the Jan. 1 Tournament of Roses parade; however, Silva was the first to deploy a helicopter in an ENG application.)

Homegrown Equipment

KTLA was certainly not alone in devising methodology for airing news events as they happened. By the late 1940s, RCA was offering a two-camera “remote” unit in its catalog of TV-specific equipment, and a number of stations either purchased such ready-made products or “rolled their own” in an attempt to supplement studio programming.

And while these smaller mobile video origination platforms could be used in coverage of a scheduled news event, spontaneity was not their strong suit, as external electrical power was required, necessitating the pre-ordering of a power company “drop,” or running heavy cables to a suitable AC source.

However, by 1952, engineers at Washington, D.C.’s CBS affiliate, WTOP-TV (now WUSA), overcame this limitation with the creation of a one-camera vehicle (a modified passenger car) for event coverage. (As little documentation survives, it’s possible that the network may have been involved in the project, as CBS was then part-owner of WTOP-TV.)

A surviving photo (on the cover) shows the unit in operation, with CBS newsman Walter Cronkite describing a news event as technicians operate an RCA camera and microwave transmitter. Power demands for this gear would have been minimal compared to those required by vans with multiple cameras, monitors and other origination equipment, and could have been met by an auxiliary AC generator driven by the car’s engine.

Despite the efforts of station and network engineering teams in devising smaller and less power-consuming mobile video origination platforms, throughout most of the postwar first three decades, the favored methodology for capturing most news events for television broadcast remained the 16-millimeter motion picture camera, due to its small form factor, ease of handling and portability.

(The next part of this series will examine the initial attempts at breaking away from news film as solid-state equipment began to replace vacuum tube-driven broadcast gear.)

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.