Increasingly Software-Centric Switchers Occupy Hybrid Space

Moving to IP and the cloud is just the first step

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Many industries have seen big-ticket hardware turn into software. Switchers, though, demand a combination of real-time performance and sheer bandwidth that has only recently become achievable in software, and has taken a while to begin affecting the high end.

Greg Huttie, vice president of production switchers for Grass Valley, said the company’s designs have long relied on both silicon and code. “Every production switcher we’ve ever put out has software involved in it one way or the other,” Huttie said. “Across the board, I’ve got hardware engineers and software engineers. The world is becoming hybrid.”

Level of Trust

That world, though, interfaces with working practices which change slowly.

“When you talk to a vision mixer or technical director, they’re basically piano players,” Huttie said. “They have a tactile feel. I sat in director’s chairs for many years, and there’s a trust level—even though I’m calling something, my technical director is in my head, lingering on shots he needs to linger on but also knowing the rhythm of the show I’m putting out. They don’t look at the keys.”

That kind of experience, Huttie continued, is increasingly in demand on shows at every scale.

“There is a growing trend where you place yourself further downmarket—not in finished features or functions, but as a smaller piece of that Grass Valley hardware,” he added. “We just delivered 48x24 in a K-Frame XP and won awards at IBC and NAB. We saw that a lot of folks want the power of a production switcher, but they wanted to reduce headcount…going for that single seat.”

Increasingly, software-defined implementations more easily fulfill the demand for a wider range of options, as Huttie explained by reference to Grass Valley’s cloud-integrated Event Producer X with its Maverik X switcher.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

“I think a better place for that single seat isn’t really for sports but events, news, corporate,” Huttie said. “Event Producer X couples things together and makes it less burdensome on body count, though we’re not advocating that you reduce your body count.”

A Connected World

Software definition has implications that reach further than feature set or scalability, according to Deon LeCointe, director of networked solutions at Sony.

“Everything we build now has to have some connectivity involved,” he said. “They have to be not only hardware for on-prem, they have to be software for cloud, SDI and IP.”

Even the comparatively recent move toward IP, though, faces unexpected pressures. “The prevailing logic is that if you’re building a new facility, or renovating, you have to take a hard look at implementing IP,” LeCointe said. “Three years ago, I would have said that the question still comes to mind.”

That idea, though, might no longer quite be universal. “When the pandemic happened, REMI became required for day-to-day operations, and it accelerated the conversation around IP tech moving toward cloud tech,” LeCointe said. “People were saying, ‘Can we skip IP and go to the cloud?’”

The answer, he said, was often no, not least because of the media industry’s uneasy relationship with metered-data exit fees. “Cost was a pretty big roadblock,” he said. “Then, the challenge of not having all your live production elements in the cloud—replay, graphics switcher elements, video shading—that just hadn’t gotten there yet.”

Given the interaction of so many complex technological considerations, LeCointe emphasized, Sony has kept things flexible.

“We opt for more of a customer choice philosophy,” he said. “M2L-X is our software-based switching platform, which can be deployed on the public cloud or on a COTS [commercial off-the-shelf] server. We’re not trying to delve into the minefield about where customers want to deploy.”

Back to Prem

A combined interest in quick, flexible scalability and cloud as a choice rather than a requirement, then, seems like the mood of the moment, according to Satoshi Kanemura, president and chief operating officer of For-A America.

“Everyone likes a 100-input big switcher, and that’s driven mostly by the technical director’s opinion,” Kanemura said. “Nowadays, what they’ve found is that sort of big event is once or twice in a year, but most operations need 20 to 30 inputs with 2 ME.”

Doing that the old way takes effort, Kanemura said. “When they increase or reduce the system, adding hardware, rewiring, recabling…they have to manage such a change,” he said. “So, software-defined is becoming a very big buzzword. One or two years ago, many people jumped into the cloud: ‘Cloud’s going to solve everything, it’s easy to increase or decrease the operation.’ What they found was that…even if they shrink the application, still using the cloud, that charge is coming every month.

“Now they’re coming back to the on-premise solutions,” Kanemura continued. “People who can’t afford a big switcher with 100 inputs can go toward software-defined. For-A Impulse can do anything a customer wants—switcher, multiview, frame sync or you can put only multiview into the server and that can be shared into the three rooms. Then, the next day, you can change it to all HDR-SDR conversion parts.”

For-A’s market position in Japan has granted it a unique position with regard to AI and the vexed issue of training data. “Now [that] cable revenue is down, most broadcasters are looking for new revenue from streaming,” Kanemura said. “They do the production in a 16:9 format, then want to trim down to 9:16 for cellphones. You can crop using AI to track the main player into the center of that 9:16…it’s that kind of AI engine.”

Making that happen has allowed For-A to leverage its relationship with NTV. “Their engineers and For-A’s got together to collaborate to build the AI,” Kanemura said. “To make a good AI, you have to give more and more data, but most AI in the market is not specified to the broadcast market; it’s more generic data they put in. [But] NTV has 70 years of archives—that AI knows how to cut, zoom, and understands the sort of scene. It’s a more broadcast-friendly AI engine.”

‘Keys to the Kingdom’

With or without AI, running a switcher on a workstation or server raises issues around the sort of real-time responsiveness that users expect. Les O’Reilly, director, switcher product management at Ross Video, described how the company has accommodated that change within an existing product line.

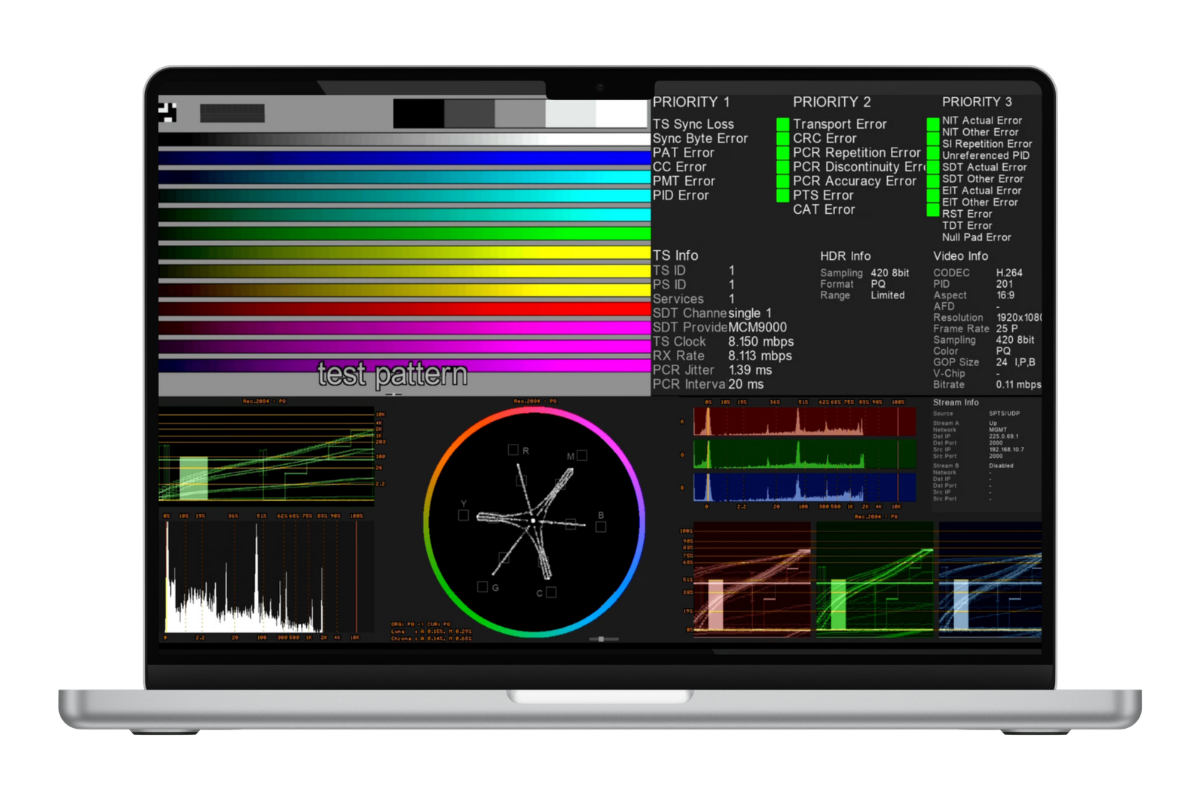

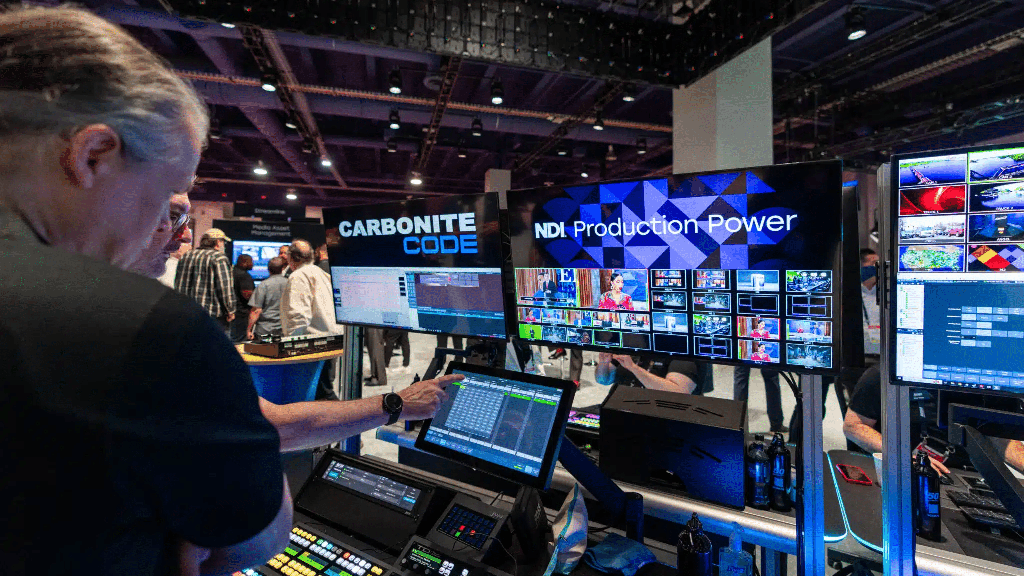

“The Carbonite family has shipped over 12,000 switchers,” O’Reilly said. “Carbonite as an operator user base was massive… and Carbonite Code launched at NAB 2024. It’s a Carbonite switcher, but instead of on an FPGA [field-programmable gate array], it’s running it on a GPU [graphics processing unit], a software-based switcher that can do some things that are different, but it still operates like a Carbonite.”

The bounds of the underlying hardware are necessarily imposed in a rather different way than the input and bus counts of a conventional switcher—though Ross’s experience in graphics has influence here.

“You have processing headroom you will run into in a software switcher,” O’Reilly explained. “In our XPression world, we have a software 3D renderer, all done in the GPU, which has a load meter. It’s showing you that you’re still rendering faster than your frame rate.”

Implementing that in a switcher running on COTS hardware, O’Reilly continued, gives users an easily-understood performance metric. “If you’re at 90%, you’re rendering 10% faster than real time,” he said. “If I see 103%, 104%, it’s telling me I’m not rendering 60 frames per second any more, I’m rendering 57. We give them the keys to the kingdom, let them build their shows and figure out what they can and cannot do.”

O’Reilly’s approach to AI’s role in the future of production switchers is pragmatic.

“I want our industry to introduce practical uses, otherwise the joke is that when a company does its keynote, the Discord group takes a drink every time they mention AI,” O’Reilly joked.

Ross’s approach leans toward making the switcher a directable part of the show itself. “We have a speech analysis tool that allows you to direct your show while talking,” O’Reilly said. “We had it on the floor—you could come up and direct it—ready one, take one, put one on the left split, two on the right—and since then we’ve refined and applied that to other products.”

Despite all this advancement, O’Reilly cautioned, the exigencies of live television have maintained the demand for traditional hardware. However, making changes acceptable to highly experienced users is, as always, a consideration.

“FPGAs keep getting bigger, badder and faster,” he said. “We’re constantly adding features and functionality, and we have to get the operator and the user to come along on the journey. So, yes, we absolutely can’t stay locked in the past, but we have to bridge to the future.”