The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Maybe it’s because I still remember being a little boy, going to the movie theater and watching “Dr. No” with my dad. For whatever reason, I’ve enjoyed James Bond movies ever since, and I’ve taken special delight in Mike Myers’ tongue-in-cheek spoofs of the franchise.

That’s probably why my mind immediately went to Austin Powers’ immortal words to actress Kristen Johnston, the Russian hit woman: “I’ve lost my Mojo!”—not once but twice—while recently scrolling through YouTube Shorts.

The first time involved TVU Networks. The company is pitching its IP transmitter—the same one or similar to the one it has sold to broadcasters for news and sports contribution. This time, however, its target market is content creators and video podcasters.

The next was a YouTube Shorts ad for

Adobe Firefly, the company’s generative AI platform that makes generating images and video fast, easy and inexpensive.

For a long time, highly priced technology played a significant gatekeeper role, separating those who could afford to create and distribute video to the public from those who couldn’t. In the 1980s, when I started covering this business, a Quantel Paintbox-Harry-Encore combo ran upwards of $1 million. An ENG truck—the only functional equivalent of an IP transmitter I can think of—could cost $100,000 or more.

But as with all other things technology, prices have fallen and performance has risen. As a result, the barrier to entry has diminished to the point where it’s nonexistent in many instances.

Distribution technology has fared no better when it comes to broadcast mojo. For quite a while, broadcasters had a lock on mass distribution. Even with the rise of the “500-channel universe” that seemed so unimaginable decades ago when I first heard the term in a college lecture hall, broadcasters, through regulation and negotiations, found a way not only to survive but thrive.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

But streaming services, connected TVs, tablets, smartphones, the internet and online video platforms have upset that apple cart with potentially devastating consequences for broadcasters.

An April Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) report tells the story: digital video advertising is on pace to account for 58% of the TV/ad spend this year, compared to linear TV, which will fall from 48% of the total last year to 42%.

Of course, many other qualities that separate broadcasting from the 162 million content creators in this country alone. Local news, sports, weather and traffic reporting come to mind. Here, too, the number of competitors has climbed as the barriers to creating content evaporate. But at least local broadcasters maintain a leg up, especially in terms of trustworthiness.

A May 2024 report from Pew Research found 71% of Americans say their local journalists do “a good job of reporting news accurately.” That’s a real strength local broadcasters must play to to set themselves apart.

Another is leveraging their resources, including content, personnel and organizational, to compete effectively in the FAST and digital video domain. On the network level, there’s Pluto TV, Tubi, Hulu, Peacock and Paramount+. Local station groups, such as Gray Media with Local News Live and Big 12 Studios, Scripps with FAST versions of diginets like Grit and Laff and Sinclair with FAST versions of its Comet and CHARGE! are in the game as well.

The most important, however, may prove to be developing new revenue sources like commercially available datacasting services for U.S. businesses better served by a one-to-many data distribution architecture than wireless unicast transmission.

Fortunately, unlike Powers—who needed a time machine to retrieve his mojo—broadcasters possess competitive advantages and opportunities they can leverage to rekindle their magic.

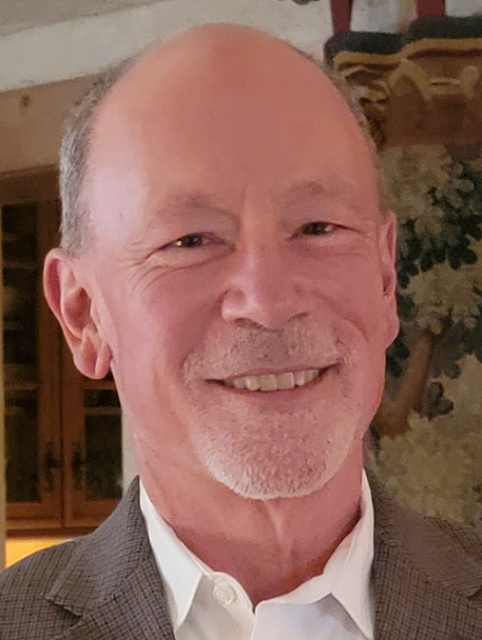

Phil Kurz is a contributing editor to TV Tech. He has written about TV and video technology for more than 30 years and served as editor of three leading industry magazines. He earned a Bachelor of Journalism and a Master’s Degree in Journalism from the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Journalism.