Vinten: 100 Years of Innovation

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

William Vinten was fascinated by the film industry from the first moment he saw a movie at the age of 16. He knew it had a future, and he was determined to be a part of it. His opportunity came in 1908 when he teamed up with Charles Urban, an American who was importing Edison products into Europe, to run his workshop in Wardour Street, then as now the heart of the film industry in London.

Vinten, an engineer consumed by a passion for precision, proved himself so capable at running Urban’s workshop that he was given the opportunity to take it over as his own business. Financed with a loan of £600 from his mother, on January 1, 1910, the doors opened and within a week the business had won its first order, for 25 Kinemacolor machines at £25 each.

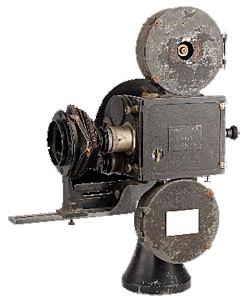

As well as building equipment for Urban, and providing a much valued repair service, he started development work on his own cameras, and the coming of war in 1914 gave him a unique opportunity. He won a contract to build a camera to be slung from the side of a Royal Flying Corps aircraft, not at this stage for reconnaissance but to show the people back home how well the fighting in the trenches was going.

In 1919 this was converted to the Model C camera for movie use, which even caught the attention of the general press: the London Evening News commented, “The mechanical running parts are wonderful in their precision”. When, in the 1970s, the company wanted a Model C camera for its museum, it was told by Brent Studios that they were still using theirs for titling, and they would have to wait until it was worn out.

Whilst four of William Vinten’s five children worked in the company, it was younger son Bill Vinten who led it into the business we know today. During the Second World War he was attached to the Royal Naval Film Unit where he became an experienced cinematographer, going on after the war to become an acclaimed lighting cameraman, first in film then in the rapidly growing field of television.

In the days before the invention of video recording, if anything was to have a life after an initial live transmission it had to be archived on film, effectively by pointing a film camera at a monitor. This is not as simple as it sounds, as the pull-down time of a 35mm camera is longer than the vertical blanking interval of a television frame.

It was the Vinten factory, which adapted its standard combined sound and picture camera to do the job. We have recordings of the royal wedding of 1947 and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, for example, thanks to Vinten recorders.

Engineering On A Pedestal

By the early 1950s image orthicon cameras were developed, which did not smear. That meant that they could be moved on shot, allowing the director to take a more movie-like approach to television production. The difference, though, was that whereas movies were shot by one camera in short takes, television used multiple cameras over very long periods. There was no commercial television in the UK at this time, and the BBC was ambitiously tackling complete Shakespeare plays, meaning an act of an hour or more without a break.

Bill Vinten recognised that this imposed very different requirements for camera mobility, which could not be met by film camera supports. Television drama used a number of sets built in a single studio, and the cameras had to be able to move swiftly and silently around the floor, following the action from set to set. Pedestals also had to support a significant weight: the first colour cameras in the early 1960s weighed upwards of 100kg without accessories. Vinten spent three years developing its hydro-pneumatic pedestal design, ignoring the advice of hydraulic engineering specialists and seal manufacturers who said that it could not be done. The first type 419 pedestals were delivered in 1956 and, along with the MkIII pan and tilt head, became the forerunners of the world-renowned Fulmar and Quattro pedestals, Vector and Vision heads.

They also set the standard for innovation in design, with products like the Heron crane which could steer and crab across the studio floor, giving directors unprecedented agility for the camera. Although he retired in 1982, Bill Vinten still retains a keen interest in the business. “I think three points come to mind when looking at the reason for our success,” he said. “Perhaps the most important was to be able to forecast what the customer needed before he realized it, and having a prototype ready. That was what really got us going in the television world. “Engineering excellence is another,” he added. “Ivor Dunningham was our Chief Engineer for many years, and like my father he was a stickler for correctness. His favorite saying was, ‘I will not have sloppy engineering in this company!’”

“Finally, we have never put price before quality,” he concluded. “We have built what was right, and even if it was double the price of a rival we have always stuck to the fact that quality is what sells.”

For the past 25 years, the task of maintaining the design excellence at Vinten has fallen to Richard Lindsay, Head of Innovation. “The team developing that first hydropneumatic pedestal established a remarkable ergonomic design that is still at the heart of the industry today. “Building on these fundamental concepts, today’s products are uniquely engineered to perfectly counterbalance the weight of the camera, and in doing so respond to the subtlest input of the operator,” he explained. “Perfect balance has been achieved by deriving the mathematical equations that precisely define how energy must be stored to keep the camera motionless at any angle of tilt or pedestal height.

“This analytical approach and the introduction of new materials which are lighter and stiffer has enabled us to devise successive new products that meet the requirements of our customers around the world, by providing optimum control and stability for cameras of any weight.”

While William Vinten would not recognize the Vinten factory today – with its mathematical modeling on computers and numerically-controlled milling machines – he certainly would approve of its determination to meet the needs of its customers with innovation and precision.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.