Have Lenses Passed Cameras in Quality?

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

SEATTLE—When high-end video people describe the major factors in image quality, you hear camera and lens, camera and lens. There's an argument to be made, however, that the order should be reversed, and we should be talking about the lens and the camera.

That's because the very top-of-the-line lenses have more than kept up with the very-top-of-the-line video cameras being employed for motion picture and television series production.

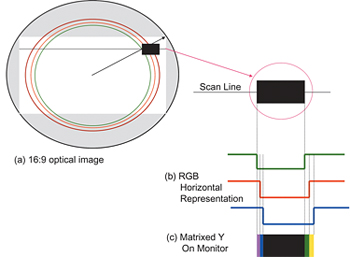

Simplified illustration of how lateral chromatic aberration causes different magnifacations of the three RGB optical images that results in color fringing on the final Luma video. "Today the lens-camera landscape is completely different than even five years ago with the development and availability of large format HD cameras," said Eva Paryzka, sales manager for Cinema Products at Thales Angenieux.

IMPERFECT FILM

Video lenses for general purpose cameras were designed to match the image capture capabilities of earlier cameras, and to be affordable, she said. "Today's camera manufacturers are merging film and video production by offering PL mount, large format digital cameras with larger and more sensitive sensors, further closing the quality gap between the film and video worlds."

It would seem that if the new single sensor cameras use a 35mm film frame-size sensor, at the same backspace, with the same PL lens mount, you could just put a high quality film lens on one of these new cameras, and get shooting.

Turns out it's not all that easy. Film is not as perfect nor as exacting as a video sensor.

Film is less perfect?

How can that be so?

Jeff Cree, vice president of Technical Services at Band Pro Film & Digital (Zeiss and Leica lenses) noted you can start with the fact that the red, green and blue color sensitive layers of film are applied at different depths on the cellulous film backing. "You can only do a compromise focus on it," he said, focusing crisply on one layer but not the other two.

Pixels on a video imager are at a prescribed depth. "On the Sony F35, it's a thousandth of a micron," he said. "So if you happen to be off, it shows. It's minute, but we're getting to resolutions where things like that are beginning to show."

Because digital cinematography began with 2/3-inch sensors, additional challenges were placed on lens makers. "With the 2/3-inch, where we've got a very small format, all of us have had to elevate the capability of the glass to give us more line curves per millimeter, because [compared to the 35mm frame] we've only got fewer millimeters," said Larry Thorpe, national marketing executive, Broadcast and Communications division, Canon U.S.A.

Lens technology developed to bring premium quality images to the 2/3-inch imagers has now trickled up to larger imager video cameras, according to Thorpe. "Some of the new 35mm PL mount lenses are claiming to have benefitted from the new designs and materials, and that they are much better than the traditional 35mm film lens."

CHROMATIC ABERRATION

Chromatic aberration is another problem that has reared its head with the new, higher resolution video cameras. Chromatic (color) aberration (error), in simple terms, occurs because of the unequal refraction of light rays of different wavelengths. Lens designers go to great lengths to correct for this, so that all colors that make up a particular piece of detail in the viewed image converge at the same point on the sensor.

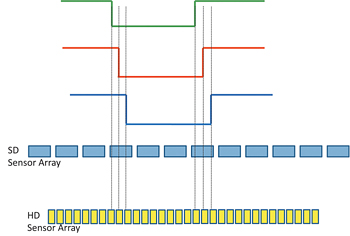

Illustrating how the separation of the three RGB optical images might not be seen by an SDTV sensor array, but could readily be seen by and HDTV sensor array. A chromatic aberration error might be seen as a slight bleeding of red, for example, on the edge of a thin line.

Fujinon National Sales Manager Thom Calabro explained that this might not really be a problem with a a lower resolution camera.

"If you have an error because you have a little bit of red bleeding, even though it's separate from the green and the blue elements of the edge, because the red, green and blue all fall within one pixel, you won't see it, said Calabro. "Now take that same error and put it on a camera that has a lot more pixels; you'll have the green and the blue part of the image on one pixel, and you'll have the red on an adjacent pixel."

Differences between film and a high-end video sensor require video lensmakers to pay more attention to chromatic aberration. First, a 35mm sensor has smaller, more densely packed pixels, which are less than half the size of 12-micron film grain. Film can therefore hide small chromatic errors, the same as they are hidden on lower resolution video cameras. A second reason film can hide such an error is that where the pixels on a sensor remain in exactly the same position as frame after frame is imaged, film grain is randomly placed on frame after frame of film. A minor chromatic shift may be visible in one film frame, hidden a 24th of a second later in the next.

Fujinon's Calabro noted that if chasing down a single pixel color shift seems like picking nits, remember that in a motion picture theater the image error will be seen on a 50-foot—not a 50-inch home screen.

One more difference between a video sensor and film is that the angle at which light rays enter a pixel must be more perpendicular to the sensor than is necessary when light rays strike the light-sensitive grain on film. "You're actually looking at shooting light into little tunnels on a sensor, and the straighter you can do that, the more illumination you will have," said Band Pro's Cree. Special elements at the back of the lens are required to achieve this.

Though a number of digital cinematography cameras are touted as 4K (4-million pixel) imaging, there's a lot of argument over whether we've actually seen a 4K camera. However, several lens makers have 4K-capable lenses ready. At NAB, we may or may not see a consensus 4K camera introduction. The lens makers are waiting for such a camera more anxiously than most. A true 4K camera will drive sales for their very best lenses.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.