Wildlife Production Marks ‘Epic’ Advances

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

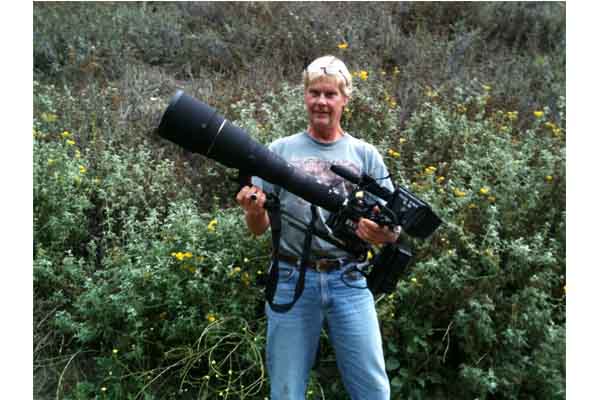

Indie shooter Jason Sturgis shoots on the Red ONE

BUFFALO, NY—Barely five years ago, Panasonic’s Varicam was the principal camera used for most major wildlife TV series, including BBC blockbusters like “Planet Earth,” and “Blue Planet.” But today you would be hard-pressed to find any major wildlife TV series relying on 720p 60 Varicams despite their superb colorimetry and “film look.”

Instead all of the momentum has been towards the new class of tapeless, single large-sensor cine-style cameras with variable frame rates called digital cine cameras or “DC cameras.”Not surprisingly, wildlife production—which has always used offspeed capture, especially slow mo—has embraced DC cameras.

Today, Varicams have been largely displaced by DC cameras in general and Red’s Epic (both X &M models) in particular. With maximum frame rates of 300 fps in 2K mode and 120 fps in 5K, a dynamic range of up to 18 stops and the highest res RAW imagery available, and much much more, this should come as no surprise.

EARLY ADOPTERS

Mark Emery, a filmmaker for National Geographic was an early adopter of Epic. “We used one of the first Epics in Alaska and the warmup time reminded me of film cameras coming up to speed for an overcranked shot but only slower,” he said. “For the most part, fights, mating and nursing were somewhat predictable, so we were usually up and running by then.” Despite some minor reservations, most Epic users, like PBS’ Nature cinematographer Joe Poncorvo, seem mainly bullish on its high resolution and unique range of cine camera features. “What I really like about DC cameras in general is their cinematic look, not just the 24p, but depth of field, dynamic range, and details I haven’t seen since shooting 16mm film,” Poncorvo said. “Not only does Epic capture a RAW image but it does so at 2K-5K. Combined with high frame rates, it’s ‘a natural for natural history.’”

Indie shooter Jason Sturgis loves Epic’s design and imaging capabilities. “I really like Epic’s small form factor, and the images are second to none,” he said. “Being able to shoot RAW gives you the most flexibility in how your image looks after color grading.”

Kennen Ward, president of Wildlight Press in Santa Cruz, Calif.,gets his edge with Epic. “With wildlife I always want to keep it fresh by filming familiar subjects in new ways,” he said. “You could never match Epic’s variable frame rates with prior cameras, nor the shallow depth of field and detail in shadow areas. Most three-chip HD cameras were flat and mid-toned to the max.”

LENSE DRAWBACKS

One drawback however is much shorter zoom lenses, critical to wildlife shooters.

“The lens choices for Super 35 sensors aren’t comparable to HD,” said Bill Murphy, series producer for PBS series “Nature.” “PL mount glass was designed for feature films and is often large and heavy. The limited focal range and lack of long zooms is fine if you’re shooting from a jeep in Africa, but not when chasing animals and changing lenses in the bush.” Some shooters reach into their toolbox and adapt 35mm still lenses, with limited focal range, but often good at the high end. Ward relies heavily on a long Nikon Mount Sigma 300-800mm. “It’s a $10,000-plus lens that works beautifully on Epic for 4K and 5K imaging,” he said.

NatGeo’s Emery often gets two shots from one with Epic. “Because the image is so massive and our final product is for TV, I can grab matched closeups of single bears from my master shot of several bears, in post,” he said. “That reduces lens changes so I can follow the action.”

Kennen Ward Wildlight Press with the Red Epic and Sigma 300-800 mm lens Some, like filmmaker Andrew Young, founder of Archipelago Films in Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y., like Epic well enough, but not as a “silver bullet” solution. “For me, the ideal camera doesn’t exist,” Young said. “If I was only shooting wildlife, Epic would likely fit the bill, but it doesn’t work as well for my other PBS doc clients who expect me to hand them the footage at day’s end, on media that they can upload themselves. With Epic, I have to spend extra hours transcoding the footage at day’s end. HD proxy files would work, but that now requires an extra recorder.”

Ideally, Young said he wants a camera that “does it all,” including high frame rates, that recordsto cheap, universal media or generates proxy files, with a window-able sensor that he can use his16mm zoom lenses, like the Zeiss 10-100mm with. “That was in the original design for [Red] Scarlet, but got lost along the way,” he added.

Most recently, Young shot a “Duckumentary” for PBS “Nature” using an Epic andSony’s new FS700. “With the 700 I didn’t have to burn card capacity waiting for ducklings to leap from their nest cavity as the FS700 buffers continuously,” he said. “It also runs quietly and has XLR audio jacks. It also records three hours of AVCHD to a $25 data card that I can hand to a client, or archive and easily backup. The slow-mo resolution is great too even at 240 fps. If only it had a decent viewfinder and fit comfortably on my shoulder.”

PRE-RECORD AND DATA MANAGEMENT

One key drawback for data-efficient wildlife capture with Epic should soon be a thing of the past, i.e. the lack of pre-record. Largely thanks to blowback from wildlife shooters, “pre-record should be included in the next firmware upgrade. I don’t think they realized how critical it is for wildlife,” Ward said.

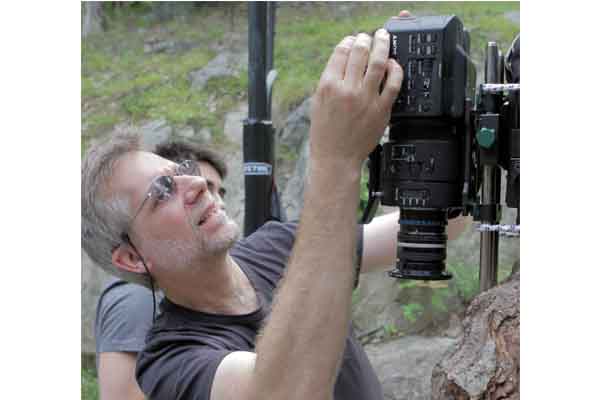

Andrew Young,founder of Archipelago Films with the Sony FS700. While pre-record on Epic will help reduce, it won’t eliminate another key challenge of shooting wildlife in 4K, data overload. “When I began shooting 4K with the Epic I soon came face to face with the biggest beast of all, data management,” said Poncorvo. I average about 21 TB of data for five weeks of shooting and may have 126-plus TB for a project, plus backups!”

Data management also impacts workflow in the field. “After filming grizzlies all dayin Alaska, my AC had to spend each night downloading Epic 4K footage, setting his alarm to change mags, a terabyte every day or two,” Emery added.

Despite its shortcomings, Epic’s unrivalled 4K and 5K picture quality is also opening new paths to wildlife storytelling, literally and figuratively. “The compactness and lightness of the new DC cameras, like Epic, has made it possible to go places and capture images not accessible before,” Poncorvo said. “Also, its ultra-high resolution can reveal details you just don’t see when shooting,like a wound on a snow monkey’s foot. This makes you wonder what inflicted it, and why, and it can change your story and how you cut it.”

Even with the great recent advances in digital imaging, 35mm film, with a resolution of up to 8K, remains the gold standard for image quality, yet its days may be numbered.

“The gap between S35 film and S35 video may never be closed, but for cost and logistical reasons, I believe that film will gently slip out of sight and we’ll no longer compare the two media,” said Barry Clark, film producer for Telenova Productions in Venice, Calif. “Meanwhile, the ongoing evolution of image sensors should bring us digitally-originated productions with wider latitude, a broader color palette and superior resolution to today’s film stocks.”

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.