Olympic Games to Debut Immersive Sound

What will masked and socially distanced crowds sound like?

TOKYO—The broadcast production of the Olympic Games is mostly a background operation provided by the Olympic Committee’s broadcast operation Olympic Broadcast Services. Their mission is to provide comprehensive coverage of all sports, of all athletes and ceremonies to global rights holders such as NBC in the United States.

OBS is also known as the Host Broadcaster and provides complete coverage including audio, video, graphics and timing/scoring—essentially providing a full broadcast production to their clients, the Rights Holder. Rights holders will then overlay their local identity on top of the Host Broadcaster production and to their home viewers it would appear to be a custom production by their network provider. In the U.S., it looks like NBC does all the work.

BEHIND THE SCENES

In a normal Olympic year, the hustle and bustle during the month of May would signal that there are about 60 days to Opening Ceremonies of the next Summer Games. Many of the vendors have arrived; the army of skilled crews have been preparing the broadcast center and venues for sports and television production; and boatloads of equipment have been arriving at a frantic pace.

Often the behind-the-scene preparation that goes into an Olympic production is unknown to the public and even to many television engineers who have never experienced such a vast undertaking from the inside.

Broadcast operations are organized by function with equal, but separate production, engineering and management departments. OBS’s engineering department is under the direction of Isidoro Moreno who is responsible for the International Broadcast Centre and all sports venues. John Pearce is the director of venue engineering and the venues are divided among five venue managers while all things audio are under the direction of Nuno Duarte who has been the full-time audio manager for OBS since 2009.

The audio manager is responsible for anything technical that impacts the audio of the games including cable, equipment, mounts, the IBC, venue improvement, audio mixing rooms and OB vans. Duarte usually spends four years, with an intense two-year cycle, preparing for the next games. The audio manager usually arrives in the host country (this year, Japan) three months before the games begin. This may seem like a long time, but every venue must be surveyed weekly and even some daily to ensure that control rooms and venue field of plays are on schedule and that every cable is labeled and located where it is suppose to be. During this period the audio supervisor can find problems and variations in plans and hopefully accommodate all impacted parties.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Efforts that should be simple like drilling holes in the floors and walls will often include venue management, equipment suppliers, sports federations and the Host Broadcaster venue and audio manager to get an approval and sign off.

In addition to technical duties, Duarte is responsible for the sound design of each sport and the particulars of implementing the microphone plan into each venue. A great amount of time and energy has been spent on developing and shaping the sound and tone of the Olympic Games.

Years of developing and testing has evolved into refined capture methods that enhance the enthusiasm of a crowd no matter what the crowd size. I am not talking about using samplers to enhance the crowds; I am referring to proper microphone placement.

IN-DEPTH AUDIO PLANS

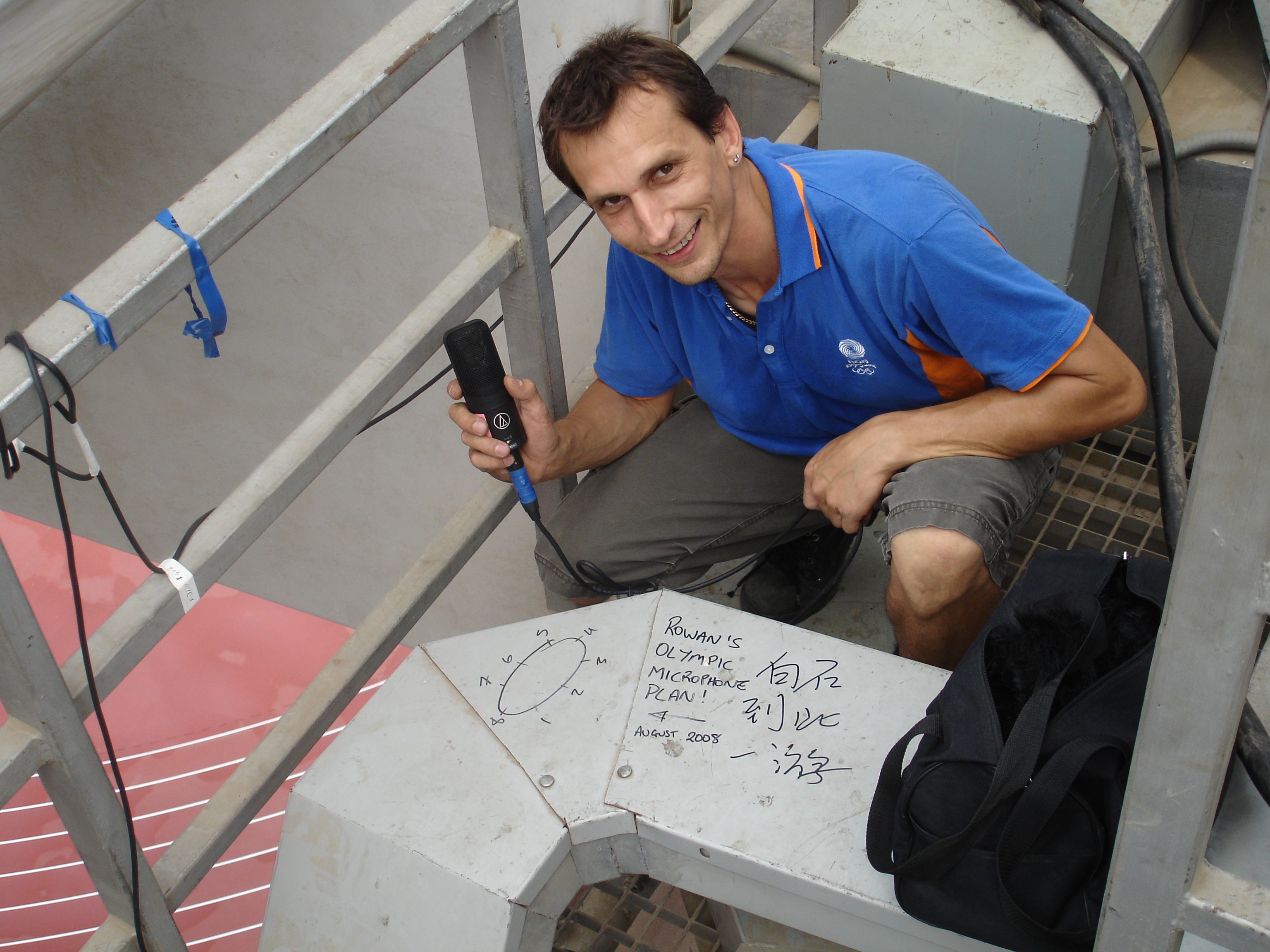

All Olympic audio plans include mounting and rigging details along with recommended "sweet spot" placement for each microphone. For example, large venues like track and field require microphones to be placed off-axis to the PA speakers. Rowan Smith has been responsible for rigging the microphones at the Olympics since 2000.

Microphones are positioned at different distances in front of a crowd zone with the microphones pointed at the audience. Microphones are often placed on ground stands so they can be moved and tuned to the seating and size of the crowd to present a “being there” impression.

The sound of sports is often associated with sizzling field sounds, PA banter and exuberant crowds. The spring of 2021 saw the return of spectators and posers to the racetrack, the horse track and baseball stadiums; and some would say sports looks and sounds normal again—in the United States.

However on July 23, 2021, the show in Tokyo will begin with Opening Ceremonies and stadiums that are empty or near empty. Crowd size always varies with the host country and any difficulties with travel and visas, but the stark reality is that a half-empty stadium is common. Crowds are usually modest for most Olympic sports anyway. For this summer’s Olympics in Tokyo there has been talk about masked, socially distanced crowds that cannot cheer or chant. I wonder what that will sound like or perhaps it means more noisemakers? I think the Japanese call them "thunder sticks" and when they are struck together it sounds like digital distortion, much more annoying than the Vuvuzelas.

The Olympics are often the stage for new technologies and production practices and the 2020 Summer Olympics, although a year late, is the debut of immersive sound. Tokyo 2020 or 2021 is the culmination of decades of work by the public Japanese broadcaster NHK to roll out Super High Definition television with 8K pictures and 22.2 sound. OBS made a commitment to implement immersive sound beginning in 2022, but will produce basic immersive sound in Japan eight months ahead of schedule.

Conceptually, immersive sound is often described as the venue experience and many of the current immersive sound designs are nothing more than atmospheric embellishments. Along with some production elements like immersive music, this level of production delivers an immersive experience without too much hassle. Immersive sound is still being developed and defined and an empty stadium is no way to practice and develop your sound. Developing a sound is not the objective of this summer’s sound production because clearly there are a lot of technical challenges for the production of immersive sound especially when there are over 30 different venues and an international crew that only works together every two years.

We are only eight months away from the Winter Olympics in China and I suggest that Tokyo 2021 is a dress rehearsal for the 2022 Games. During 2020, spectator-less stadiums were the norm with silly looking cardboard cutouts and audio samples of crowds. At the time of this writing I cannot imagine what Japan might do, although we will soon find out.

Dennis Baxter has spent over 35 years in live broadcasting contributing to hundreds of live events including sound design for nine Olympic Games. He has earned multiple Emmy Awards and is the author of “A Practical Guide to Television Sound Engineering,” published in both English and Chinese. His current book about immersive sound practices and production will be available this fall. He can be reached at dbaxter@dennisbaxtersound.com or at www.dennisbaxtersound.com.

Dennis Baxter has spent over 35 years in live broadcasting contributing to hundreds of live events including sound design for nine Olympic Games. He has earned multiple Emmy Awards and is the author of “A Practical Guide to Television Sound Engineering,” published in both English and Chinese. His current book about immersive sound practices and production will be available in 2022. He can be reached at dbaxter@dennisbaxtersound.com or at www.dennisbaxtersound.com.