The Videotape Recorder Turns 50

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Routine NAB preview event showcased revolutionary technology

FALLS CHURCH, VA.

In an age when video cameras and recording devices are virtually everywhere, it's difficult to believe that it wasn't always possible to walk into a Wal-Mart or Best Buy store with $50 and leave with a new video recorder.

The science of magnetically recording video images is so mature today that it's taken completely for granted, but that was not always the case. Television broadcasting as we know it appeared in the mid-1930s. Video recording technology lagged by another 20 years.

BREAKTHROUGH

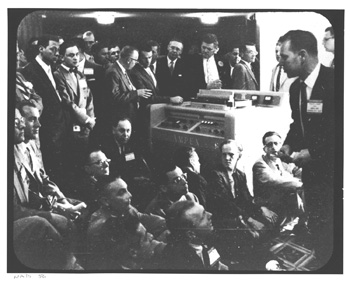

Imagine a large meeting room 50 years ago filled with 200 people assembled for a more or less routine briefing. The only thing slightly out of the ordinary is a video camera trained on the speaker and some monitors sprinkled around the room. However, television is no longer a stranger and the presence of even large tube-type cameras of that era had become fairly routine.

The event was a Saturday pre-NAB (then the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters) meeting of CBS affiliate owners and managers. The setting was the Normandie Lounge in Chicago's Conrad Hilton, the speaker was William Lodge, CBS engineering vice president and the date was April 14, 1956.

During his remarks, Lodge mentioned a new technological breakthrough, but was not specific. At the conclusion of his address, he remained at the podium. As the crowd began to murmur and break up, the video monitors went from black to an image of Lodge. Only this time, Lodge was still making his presentation, not standing silently.

This was a seeming impossibility, as the only means for preserving video images was kinescope recording, a process in which a special motion picture camera photographed a television monitor. When the recording was finished, the film had to be removed and sent away for developing. Under normal circumstances, this could take hours.

The crowd, realizing that they were experiencing something very unusual, became hushed and locked onto the monitors, viewing an image of Lodge that was indistinguishable from the video seen just moments before. Again, this was quite uncanny, as even the best "kine" had a distinctive look that set it apart from the live video it had captured.

(click thumbnail)

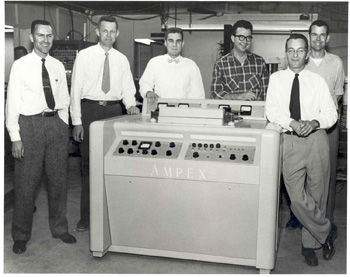

The VTR design team: (L to R) Fred Pfost, Shelby Henderson, Ray Dolby, Alex Maxey, Charles Ginsburg, and Charles Anderson Then a curtain opened, revealing a strange machine and four individuals hovering around it. The crowd couldn't restrain itself and amid cheers, whistles, back slappings and applause, began pushing and pressing in around the world's first video recorder and part of the team that had made it possible. Some even stood in chairs to get a better look at the device that was making this miracle possible.

That was the scene 50 years ago this month.

Practical video recording had been born. The machine was the Ampex Mark IV VTR prototype, which was to become the VRX-1000, the great-granddad of all video recorders. It was the star of the convention and even though Ampex had set a selling price of $45,000 for production models (more than $320,000 in 2006 dollars), orders were written that week for more than 70 machines. (Market research conducted prior to the show indicated that there would be a demand for no more than a dozen globally.)

CBS got the first delivery and put it on the air in late November that year to air the West Coast feed of "Douglas Edwards and the News."

This eliminated the requirement for Edwards to have to repeat his broadcast for the Pacific Time Zone. However, as the video recording technology was so new, CBS made kinescope recordings as backup and had them at the ready "just in case" during the first month of the new machine's use.

Recording of video goes back to the late 1920s when television pioneer John Logie Baird made recordings of his 30 line images on ordinary 78 rpm phonograph records. What was so special about the Ampex recorder and why did it take so long to come to market?

Those who can't remember a world without VTRs perhaps have little comprehension of the tremendous technical challenges involved in electronically recording television images. To put the problem in perspective, magnetic audio recording evolved over several decades and by the late 1940s was fairly mature when Ampex introduced its first audio machine.

To capture and reproduce high-quality audio, a recording device needs to have a passband of some 20 Hz to 18,000 Hz, or about 10 octaves. To record acceptable video, this had to be stretched to 18 octaves.

Other groups had been working on video recording schemes for at least five years prior to the success of Ampex. All relied on pulling tape past fixed heads at high speeds.

The BBC's efforts resulted in a machine known as VERA (Vision Electronic Recording Apparatus). It moved 1/2-inch tape at 16 feet per second, with a 21-inch reel of tape providing a mere 15 minutes of recording time. Video response was capped off at 3 MHz and heavy leather gloves to provide assistance with reel braking were part of the operator's toolset.

(click thumbnail)

The world’s first videotape recorder assembly line at the Redwood City, Calif. Ampex plant Another U.S. group established by Jack Mullin, the engineer who introduced audio tape recording to America, and funded by singer Bing Crosby, also devised a longitudinal video recorder. This machine spread the video across multiple tracks on a 1-inch tape running at a mere 120 inches per second. It made pictures, but as the response topped off at a bit over 1.5 MHz, it really wasn't up to broadcast applications.

Not one to be left out or outdone, RCA's David Sarnoff mandated that his R&D people build a video recorder. In a rather questionable move, the top audio engineer there, Harry Olson, was given the job. Even though RCA held a patent on rotary head recording, Olson simply tried to scale up a conventional audio transport to do the job.

His first machine used 1/2-inch tape pulled at 30 feet per second. It took 7,200 feet of tape to provide four minutes of recording time and the pictures were not much better than those of the other groups. As relatively crude as the kinescope recording process was, none of these video recording technologies could equal its quality, storage time and ease in handling.

Ampex engineers early on saw the futility of longitudinal recording for video and based their efforts on a rotating head design first patented for audio in 1938 by an Italian inventor. The Ampex work was kept under wraps, and due to changing economics, was actually terminated at one point. This group consisted of Charles Ginsburg, the team leader; Charles Anderson, FM expert; Ray Dolby, then an engineering student and later a household name in the audio field; Shelby Henderson, master machinist and model maker; Alex Maxey, the mechanical genius behind the rotary head design, and Fred Pfost, who solved the problem of making practical high-speed recording heads.

In addition to discarding high-speed longitudinal tape movement for achieving the necessary writing speed, the Ampex team also realized that FM offered some advantages not available with conventional recording technology, and could possibly help in squeezing those additional octaves onto tape. Research was started on an FM system that smacked of heresy--the carrier frequency was very near the highest modulating frequency and conventional wisdom dictated that the carrier frequency must be at least 10 times that frequency.

The carrier frequency was dictated by available tape head technology and this rather revolutionary FM system resulted in some mathematically interesting consequences (sidebands which could fold over into the desired signals). Nevertheless, the thing worked, and worked better than any AM signal system could have, producing a greatly improved S/N ratio and compressing the necessary 18 octaves into the space of three.

The video recorder shown to the crowds in Chicago, and destined to set the standard for all video recording, used a special 3M 2-inch tape, a four-head quadraplex or "quad" rotating head assembly and pulled tape along at a sane 15 inches per second. It could provide up to 90 minutes of recording time and recorded the full 4.2 MHz bandwidth needed for 525-line television.

FAR FROM PERFECT

These early machines were bulky (they could not fit through an ordinary doorway), weighed more than 1,000 pounds and the scores of vacuum tubes used consumed a very substantial amount of electricity.

(click thumbnail)

An early Ampex VTR installation at CBS An external supply of compressed air and a vacuum system were necessary for operation. Operational costs were extremely high by today's standards. An hour's worth of 2-inch tape cost hundreds of dollars and the life of the machine's video recording head assembly was measured at best in just a few hundred hours. This figure was sometimes much lower and head refurbishment costs amounted to $1,000 or more.

The recorders were finicky and required a highly skilled operator and a fairly intensive setup and adjustment period before each use. A great deal of heavy maintenance and specialized tools were needed to keep them operational.

Video was not instantly available, as the machines took several seconds to get up to speed and stabilize. This required care on the part of operators and TDs in making sure that the requisite back timing and pre-roll were done. Due to mechanical differences in the rotating head assemblies, none of the early machines produced recordings that were really fully interchangeable.

The networks got around this by making sure that the head assembly used for recording also did the playback. This had to be carried out in the extreme if a show was recorded in Los Angeles and then played back in New York. In such cases, the video head was removed from the recorder and shipped along with the tape. Still, the convenience and video quality made the machine an instant success.

RCA saw the handwriting and scrubbed their longitudinal recorder R&D work, licensed Ampex technology and shortly rolled out their own quad machine, the TRT-1. RCA was the only other serious competitor to Ampex and in the years that followed, a tech war of sorts evolved between the companies.

Improvements were fast and numerous: air bearing heads, rotary transformers to replace slip rings, time base correction technologies, color recording, genlockable servo systems, high band recording, velocity compensation, electronic editing, better head alloys, low-noise tape coatings, vacuum column tape handling... the list of these "one-up-manships" continued right on up until the end of 2-inch recording developments in the 1970s.

Ampex's quad design endured for well over 20 years, until it was gradually displaced by 1-inch type "C" helical scan technology.

An incredible 50 years later, there are some quad machines out there still at work. According to Pat Johnston, director of project management for AheadTek, his company is rebuilding about 200 quad heads per year.

RCA is now just a dimming memory in the broadcasting landscape. Ampex continued to build new VTR models into the dawning of the digital age, but was essentially out of broadcast video recording by the end of the millennium. The company name still exists in connection with data recording and archival storage technology, but isn't seen much in television stations anymore.

With the advent of digital television and the DVD and hard-drive video recording that it spawned, videotape use is on the wane. Some of the biggest producers of magnetic tape pulled out of the market years ago. The phrases "tapeless television station" and "the end of tape" entered the vernacular at least 10 years ago.

With the exception of data cartridges for archival recording, these prognostications may well may come to pass. Even that application appears shaky, as data packing advances in optical disc recording methodologies seem destined to surpass what can be done with magnetic storage.

For decades, video recording quality has been such that it is indistinguishable from live video. Recording devices have become so reliable and commonplace that no one is excited in the least by the words "video recording."

Still there are a few remaining from that crowd, who, 50 Aprils ago, witnessed the first demonstration of real video recording and who remember the electricity and shivers of excitement that went with it. There are many more that recall their initial encounter with videotape and the fascination that came with it--the solid snap as the guide shoe engaged; the pleasing, almost musical "buzz" produced by that massive, yet very delicate, rotary head assembly spinning at its 14,400 rpm rate; and the smell of the tape coating as the heads literally tore into it.

(click thumbnail)

The Ampex video recorder is unveiled at the NARTB show in Chicago, April 14, 1956. An early video recording textbook described the rotary head recording process as one in which the head's pole pieces "created a localized dimple, moving across the tape." Actually, something far more profound happened as the heads moved. They froze time and left behind moving images for future generations to witness and enjoy. They also launched a business that has become the single largest element in broadcasting and a technology that has become an integral part of hundreds, if not thousands of other businesses.

What Was It Like?

There is a special kind of captivation or fascination that goes along with being witness to an event destined to have historic significance.

John T. Moore, the youngest witness to the Wright brothers accomplishment in December 1903 was reported to have run down the beach at Kitty Hawk yelling at the top of his lungs to anyone listening, "They done it! They done it! Damned if they ain't flew."

This atmosphere was certainly present that Saturday in April 1956 when Ampex showed the world it had perfected a video recorder.

If anyone should know what the situation was like in the Hilton's Normandie Lounge, it would have to be Charles Anderson, one of the Ampex VTR design team members who was there with the Mark IV machine. As Anderson described it:

"The (CBS) affiliates meeting was in the Normandie Lounge, the foyer of a ballroom. We were in an alcove there with the machine, behind a curtain. No one knew we were there. CBS had cameras and monitors scattered around the lounge, but that was nothing unusual.

"There were a lot of people in the room and on cue we started to record. Bill Lodge was explaining to the group that there was something new they wanted to show. On another cue, we rewound the tape and started playing it back.

"All of a sudden, there was a deafening silence.

"Did we screw up somehow?

"Then came a roar. The curtain was opened and people started to swarm back around the machine. Before we knew it, we were knee deep in people."

Anderson recalled that Charles Ginsburg, Fred Pfost and Phil Gumby were with him that day.

"That machine was demo-ed a lot. It was a very successful show for the network. That night, Ginsburg and I went out with Blair Benson from CBS to the Blue Angel to celebrate. Ginsburg was dancing on the tabletop."

Pfost also recalled the silence that initially ensued once the playback started.

"There was total silence for about 15 seconds. Then people began to realize what they were looking at. It made such an impression on me that I get tears in my eyes telling the story. People screamed and clapped for probably 10 minutes."

After that presentation finally ended, Ampex executives realized from the reaction of the crowd that the company had a hit on its hands. The CBS demonstration had been just that--a closed-door session for invited guests. It was hastily decided to rent hotel space to exhibit the VTR for the balance of the show. Anderson remembers that part of the experience as not being so euphoric:

"Very early the next morning [Sunday], the VP was on the phone with orders to move the videotape machine. We weren't at our best from the night before, but we went ahead and moved it there. From then on there was a steady stream of people throughout the rest of the show."

Pfost also recalled relocating the recorder.

"After the demo we took the machine up to the fourth or fifth floor in the hotel. For the rest of the show that room was totally full. At the end of the week, the orders for machines amounted to more money than Ampex had been doing in a whole year. We went back [to Redwood City] and had to figure out how to build all these machines."

Ray Dolby stayed behind in Redwood City to demonstrate video recording for members of the press and Ampex executives. The reaction was similar to that in Chicago, according to Dolby.

"Everyone was enthusiastic, there was a lot of applause and laughing and clapping... but on the other hand, you have to remember this was an engineering lab, not a plush hotel room, as they had in Chicago," he said.

Even so, sales orders were being written on an almost non-stop basis. According to one source, Ampex ran out of sales forms and was writing orders on any scrap of paper they had at hand.

What Was It Like?

There is a special kind of captivation or fascination that goes along with being witness to an event destined to have historic significance.

John T. Moore, the youngest witness to the Wright brothers accomplishment in December 1903 was reported to have run down the beach at Kitty Hawk yelling at the top of his lungs to anyone listening, “They done it! They done it! Damned if they ain’t flew.”

This atmosphere was certainly present that Saturday in April 1956 when Ampex showed the world it had perfected a video recorder.

If anyone should know what the situation was like in the Hilton’s Normandie Lounge, it would have to be Charles Anderson, one of the Ampex VTR design team members who was there with the Mark IV machine. As Anderson described it:

“The (CBS) affiliates meeting was in the Normandie Lounge, the foyer of a ballroom. We were in an alcove there with the machine, behind a curtain. No one knew we were there. CBS had cameras and monitors scattered around the lounge, but that was nothing unusual.

“There were a lot of people in the room and on cue we started to record. Bill Lodge was explaining to the group that there was something new they wanted to show. On another cue, we rewound the tape and started playing it back.

“All of a sudden, there was a deafening silence.

“Did we screw up somehow?

“Then came a roar. The curtain was opened and people started to swarm back around the machine. Before we knew it, we were knee deep in people.”

Anderson recalled that Charles Ginsburg, Fred Pfost and Phil Gumby were with him that day.

“That machine was demo-ed a lot. It was a very successful show for the network. That night, Ginsburg and I went out with Blair Benson from CBS to the Blue Angel to celebrate. Ginsburg was dancing on the tabletop.”

Pfost also recalled the silence that initially ensued once the playback started.

“There was total silence for about 15 seconds. Then people began to realize what they were looking at. It made such an impression on me that I get tears in my eyes telling the story. People screamed and clapped for probably 10 minutes.”

After that presentation finally ended, Ampex executives realized from the reaction of the crowd that the company had a hit on its hands. The CBS demonstration had been just that—a closed-door session for invited guests. It was hastily decided to rent hotel space to exhibit the VTR for the balance of the show. Anderson remembers that part of the experience as not being so euphoric:

“Very early the next morning [Sunday], the VP was on the phone with orders to move the videotape machine. We weren’t at our best from the night before, but we went ahead and moved it there. From then on there was a steady stream of people throughout the rest of the show.”

Pfost also recalled relocating the recorder.

“After the demo we took the machine up to forth or fifth floor in the hotel. For the rest of the show that room was totally full. At the end of the week, the orders for machines amounted to more money than Ampex had been doing in a whole year. We went back [to Redwood City] and had to figure out how to build all these machines.”

One of the attendees, a small-market station owner, recalled that the demand to see the machine was so great that “timed” tickets for admittance were being issued by Ampex.

“I got in on the second or third day. They recorded Art Linkletter and played it back. It was quite an achievement. However, the machine cost more than I had invested in all the rest of my equipment, so I knew it would be a while before I could afford one.”

Even so, sales orders were being written on an almost non-stop basis. According to one source, Ampex ran out of sales forms and was writing orders on any scrap of paper they had at hand.

-- James E. O’Neal

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.