HEVC, Ultra HD & the Telecom Threat

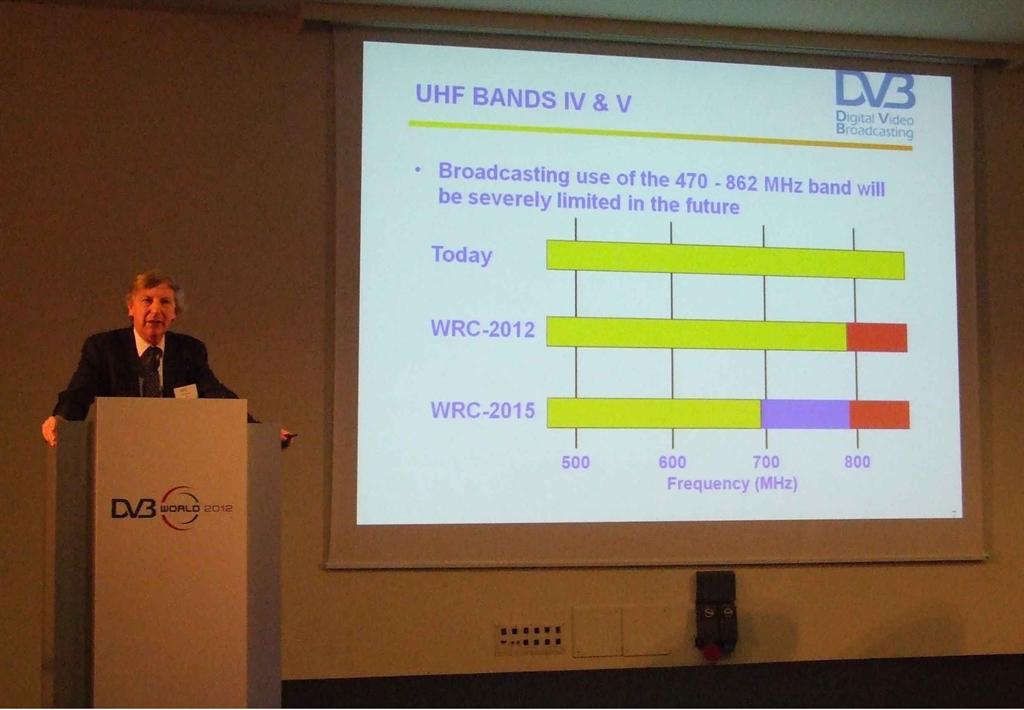

Phil Laven telling the audience about possible future threats to TV spectrum, at last year’s DVB World.

From a broadcaster’s point of view, New Year’s Day 2013 was undoubtedly celebrated Jan. 25. That is when the International Telecommunications Union announced the first-stage approval of the new video codec H.265, also known as HEVC, for high-efficiency video codec.

While some broadcast-grade HEVC encoders were disclosed during 2012, the first end-user decoders were showcased at CES 2013, about 10 days before the ITU announcement.

The new codec seeks to achieve the same video quality of the established H.264/AVC codec using just half of the bandwidth. The final figures seem to confirm initial hopes. The École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne EPFL evaluated the subjective video quality of HEVC at resolutions higher than HDTV, and the study highlighted that a bit rate reduction ranging from 51 to 74 percent can be achieved based on subjective results, while reduction based on peak signal- to-noise ratio (PSNR) values was between 28 and 38 percent.

Those are two standard ways to measure the efficiency of a video coding standard. The first is based on the subjective (human) assessment of video quality. PSNR is based on an objective metric.

The results coming out from these two evaluation methods usually differ, but at the end of the day the subjective one is the most important way to measure a video coding standard, since humans perceive video quality subjectively. It’s not the best one, it’s just the one that can drive developers to a better user experience.

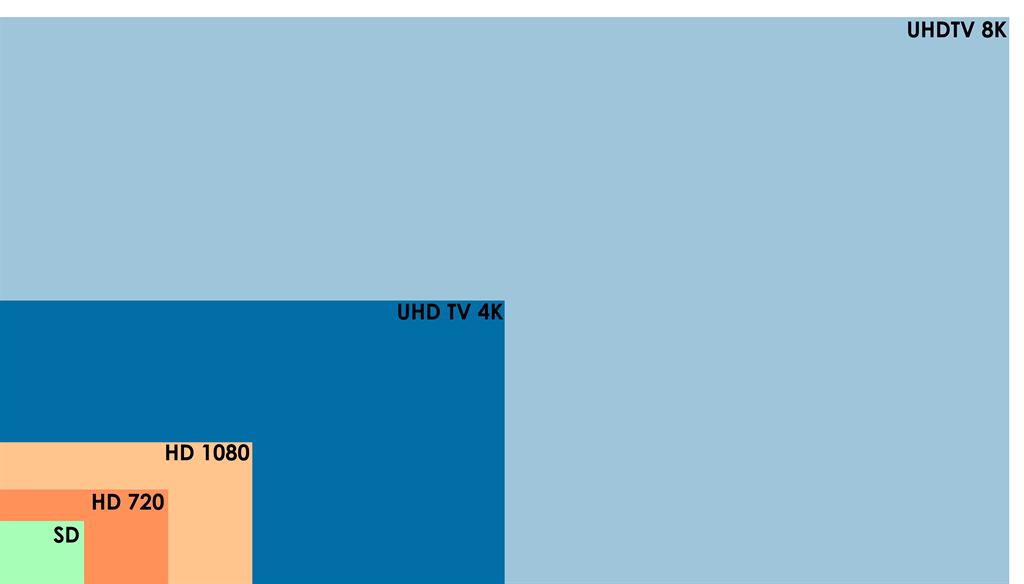

Comparing TV format resolutions and pixel numbers. In a bit more technical way: PSNR doesn’t take into account the saturation effect of the human visual system. PSNR also can’t estimate the ultimate nature of the artifacts: AVC compressed sequences feature some blockiness, while HEVC research tried to get a more “analog” effect. As a result, HEVC artefacts tend to smooth out the content, which is generally less annoying.

So HEVC looks good, according to the EPFL study, and that’s great news. If all global video content was compressed using HEVC, more than 25 percent of the current global network load would be freed up. Achieving this by implementing a single codec is amazing.

DUAL USE ...

Let’s look again at the EPFL study. They deeply tested HEVC “at resolutions higher than HDTV.” HEVC was not designed just to squeeze bandwidth. Since the very beginning HEVCalso was targeted at making Ultra HD television possible without the need to replace every existing broadcasting medium, including satellites.

A single 8K frame features 8,192 x 4,320 pixels, that is to say 33 megapixels, which is 16 times the pixels of a full-HD frame.

Let’s forget for a moment that Ultra-HD will probably feature more than 25 fps. You can broadcast a decent full-HD program at 10 Mbps (H.264). Using the same codec, this program at 8K resolution would feature a bit-rate equal to 16 times 10 Mbps, or 160 Mbps.

No terrestrial broadcasting system could deliver such a huge bit-rate in a 8 MHz frequency bandwidth (a stunning 20-bit/ Hz), and nor could any (existing) satellite transponder do it. So, to preserve at least the satellites already in service, and to save a lot of power in the future ones, it was clear that 8K broadcasting could make sense only with a suitable codec, able to squeeze the required bit-rate to sustainable levels.

With HEVC, 4K could be the near future. With the video and cinema industries already edging toward it, HEVC could shrink the 4K images (more than 8 megapixels each, 4x full-HD ones) in a compressed 20 Mbps stream.

That is to say, two 4K programs in a single DVB-T2 emission, and some in a satellite DVB-S2 transponder. A viable figure.

HEVC specs were also designed to suit content capture systems that feature progressive scanned frame rates. Standard display resolutions span from QVGA (320×240) to 4320p (8192×4320). Further, HEVC features improved picture quality in terms of frame rate, noise level, colour gamut, and dynamic range.

3G NETWORKS MAXED OUT?

Meanwhile, the notion that mobile video is pushing 3G networks to the verge of collapsing appears to be a myth. Last September, Analysys Mason (a consultancy firm deeply involved in the telecommunication market) published an amazing report that clearly stated that, far from growing dangerously fast, mobile data traffic may not grow sufficiently fast to stop the mobile industry from shrinking.

The reason: The disruptive effects of Wi-Fi are limiting the rate of growth, and operators will have to adjust their strategies to a different reality: mobile data growth, which had once threatened to overwhelm networks, should be growing at a more manageable pace, even in fast developing economies.

So why the panic over 3G networks collapsing? “Forecasting mobile (cellular) data traffic has been bedevilled by analyst excitability, the interests of vendors and operators (especially spectrum lobbyists), plus general innumeracy and wildly mobile- centric and content-centric views of telecoms,” the Analysys Mason report said.

So let’s be clear: overall mobile data traffic has to be properly sliced into “cellular” traffic and“Wi-Fi”traffic.

Cellular traffic is what you have when you’re driving or walking. It’s quite uncommon watching a video on your smartphone when driving your car. Hence, this mobile traffic will generally be made of “low bit- rate” traffic, e.g., e-mail and social network updates.

When you’re on a train, or sitting in a coffee-bar, you would probably drain higher data volume by watching videos, downloading presentations, and catalogs. But you will likely be connected to the Wi-Fi access point in your office, at your home, or in the restaurant.

So none of this traffic is flowing through the supposedly crowded cellular data networks. Access points are usually fed by wired landlines data connections. The nicest thing is that the competitor capable of diverting data traffic from cellular networks – thus preventing mobile network operators from charging their customers for said traffic – usually is just a separate business unit of the same mobile network operator, namely a landline telecom operator.

Anyway, the 800 MHz band has gone away from broadcasting. 700 MHz, in its turn, is packing up its bags.

WHITE SPACE THREAT

The next threat is a bottom-top one. I mean the so-called “white spaces.” These are frequencies allocated to a broadcasting service but not used locally, and guard bands between used channels.

In Europe, two parties are facing each other in a regulatory battle over white spaces.

The first are those who claim that white space devices must be able to detect their locations, then poll a centralized database for the locally available white spaces and tune to the centrally- approved white spaces only. The second are those who believe in these devices finding white spaces themselves by scanning for open channels, and capturing whatever space happens to be unused.

You can easily imagine what will happen to broadcasting should the latter party will prevail. Nobody knows if all this spectrum mess was really unavoidable, as a natural evolution of both times and technology. Or perhaps the whole broadcasting world is facing a hostile takeover by a party that has all: A clear strategy, a multi-national shape (unlike any broadcaster) and, for sure, a lot more money than broadcasters themselves.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.