When the Glow Starts to Go: When to Change Your LED Lights

Slow fade-out makes knowing when it’s replacement time a challenge

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We tend to think LED lights will last forever—they don’t, although 50,000 hours, plus or minus, is a very long time compared to legacy light sources. Assuming some driver component doesn’t suddenly fail, LED lights die more subtly; they slowly fade away. The challenge is knowing at what point they need to be replaced.

LEDs don’t burn out the way incandescents do. Instead, they tend to degrade gradually like fluorescents, but without the telltale tube-end blackening. At some point, following many hours of service, they will wear out and need to be replaced. That point is now being approached by the earliest adopters of LED lighting.

The lighting industry’s benchmark for the end of service life is defined as when LED output drops to 70% of its initial brightness. This is called the “L70” standard, where the “L” stands for lumens, and the 70 is the remaining percentage of its original brightness. Once output drops to that level, they’re declared “burned out.”

That brightness criteria only tells part of the story about how LEDs die, however. LEDs don’t just fade away; their color balance and fidelity can change over time.

Tuning Into Colors

Bicolor and full-color LED fixtures produce their intended shades of light by mixing several spectrum-tuned LEDs in combination. The mechanism for generating usable light from an LED is this: High-frequency (blue and UV) light stimulates the phosphors to emit a lower frequency of light. Think of it as changing largely invisible energy into colors we can see. The various phosphor “recipes” are “tuned” to produce different colors. Ah, science!

The resulting blend of light can remain correct for a very long time, but not forever. That’s because the phosphors slowly break down from heat and material fatigue. This is less of an issue with remote phosphor lights because their light-emitting layer is some distance from the LED chip’s most intense energy. The trade-off is that remote phosphor lights are limited to a single color temperature.

As phosphors wear unevenly, the color changes. Those “white” presets no longer work as intended, and color fidelity drifts. Some manufacturers (like ETC) already compensate for LED “droop” (or reduced output) caused by heat by adjusting individual LEDs in response to fixture temperatures in order to maintain proper color balance. A similar approach might one day address phosphor aging as well.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

First-generation LED studio lights were fairly primitive compared to what’s available today.

Early LED fixtures strained to meet our industry’s high standards for color quality. A major hurdle is that LED lights are discontinuous spectrum sources, much like fluorescent. Sawtooth gaps in their spectrum profile can make flesh tones look splotchy and unnatural. More “full-spectrum” lights put their energy into higher color quality at the expense of brightness. In the early days of LED lights, the efficiency was too low to do a decent job of both. That problem’s been solved.

Too Many Metrics?

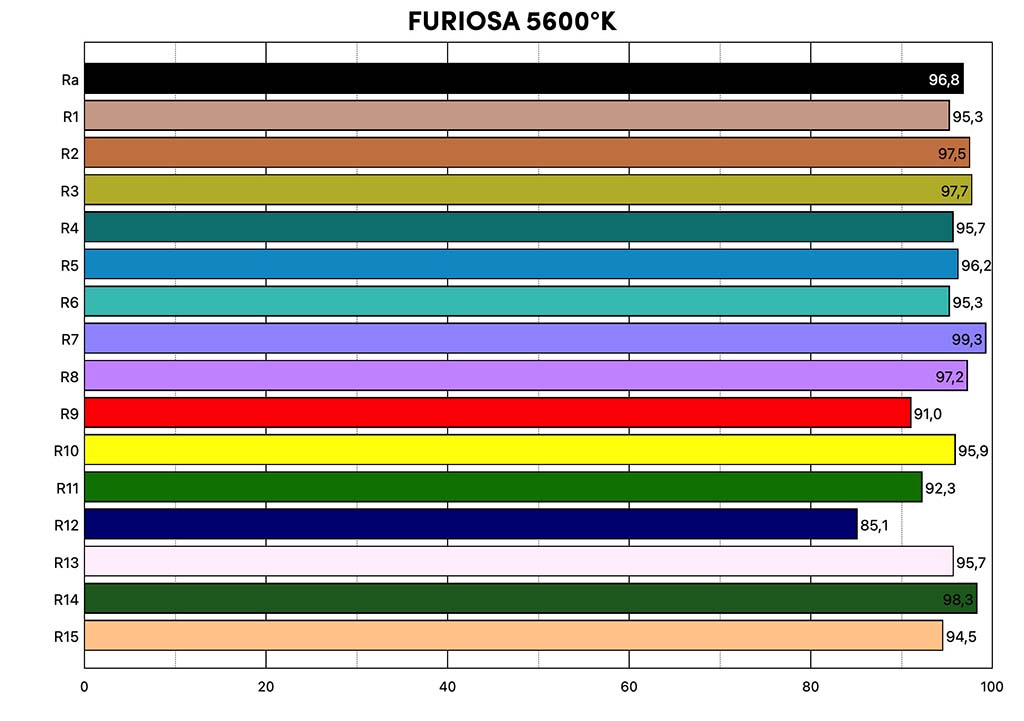

As color quality has become more important, so has our need to evaluate it. In fact, there are so many different metrics that it can be confusing. Of the many competing scales for color fidelity, including TLCI (Television Lighting Consistency Index), SSI (Spectral Similarity Index) and TM-30 (my current favorite), it’s CRI (Color Rending Index) that’s probably most familiar. We’ll use that as we discuss standards.

Every respectable LED studio light sold today has an excellent CRI score in the mid to upper 90s on a scale of 100. Excellence is now so common that you can find 90 CRI “bulbs” for your table lamp at the grocery store. Our studio lights should be at least that good. So, how do we ensure our lights measure up?

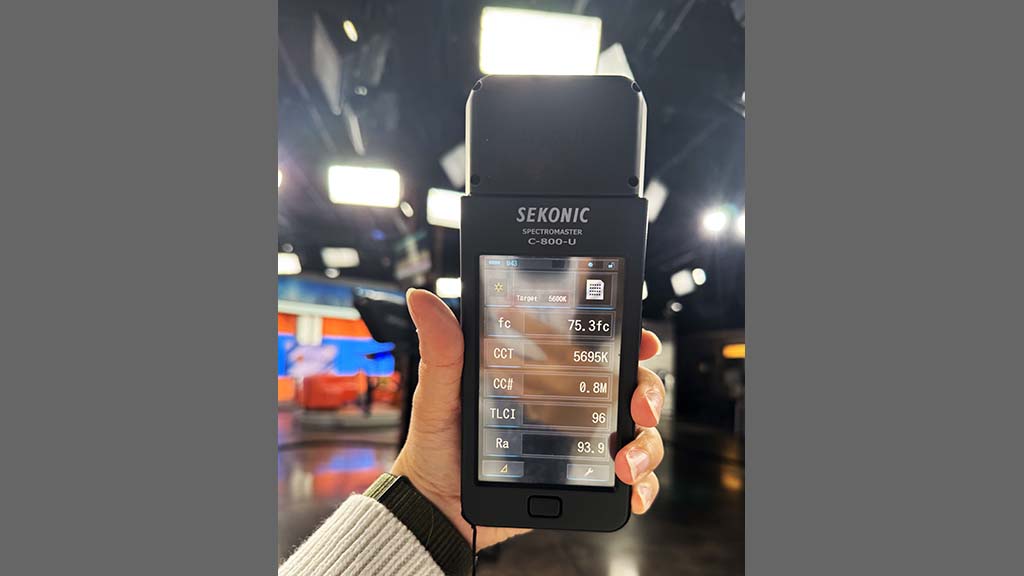

While an illuminance light meter can measure intensity, you’ll need something like the Sekonic C-800-U Spectrometer to know if the color fidelity is up to snuff.

Consider it a pass/fail test—anything less than 90 CRI is a “fail,” particularly for the important R9, R13 and R15 chips, which impact flesh tones.

Few LED lights from 10 or 15 years ago will clear this hurdle because the bar has been raised. LEDs are brighter, more efficient and have better color quality than ever. Improvements in LED design mirror the early days of computer chips: Each new generation outperforms the last.

“Close enough for TV,” like “state of the art,” is a moving target.

Better Resolution Needs Better Lighting

The urgency to upgrade your lights will be influenced by what’s considered “good enough.” Nothing’s entirely obsolete if it can still provide some service. After all, when fluorescent studio fixtures were first introduced, 80 CRI was considered “fine.” Today, what defines “close enough” when your audience is watching on 4K OLED monitors?

Can I just upgrade my old fixtures?

From an end-user perspective, it would be great if you could upgrade light engines as they fail. Unfortunately, the industry doesn’t work that way. With few exceptions, such as some Brightline, Kino Flo or Rosco fixtures, there’s often no way to repair, let alone upgrade, the light engine.

That inability to upgrade, or even repair, is a neglected issue in the broader lighting industry. Sadly, most fixtures are destined to be trashed when they reach the end of their useful service. Manufacturers should be encouraged to do better by our willingness to pay the price for fixtures that can be repaired or upgraded.

If your older fixtures are still working, perhaps they can fill secondary roles on your next studio set—if not the more critical task of lighting talent. Using “old school” color-

correction gels can help extend their usefulness. But remember that 10-year-old fixtures are unlikely to make it to 20 unscathed. Should your lights fail the test today, it’s time to plan and budget for their replacement tomorrow.

Educating your management team on the predictable life cycle of LED lights can help dispel the notion that they last forever. People less involved with lighting may not yet understand how much the technology has transformed. It’s no longer just replacing a burned-out lamp; it’s replacing the entire light fixture—at least for now. That may change over time, but the reality today is that LED lights don’t simply die—they fade away.

Bruce Aleksander is a lighting designer accomplished in multi-camera Television Production with distinguished awards in Lighting Design and videography. Adept and well-organized to deliver a multi-disciplined approach, yielding creative solutions to difficult problems.