Video editing goes out in the field

Standing at a Moviola or Steenbeck may have been a solitary life, but editing is becoming more and more a collaborative undertaking. It may be the executive producer wanting to avoid any surprises and see how the program is going to turn out, or it could be a lead editor who is using assistants working in parallel to speed up the turnaround of a program.

From video-assist on the camera through the processes of post production, everyone involved wants to see what is happening. To the craftsman who wants to wait until the job is finished before raising the curtain, this new and open access to all stages of production may seem unwanted. However, the pace of modern production means that many parties want to follow the post-production process. The producer will want to minimize risk and avoid any reshoots or re-edits should scenes prove unsuitable for the final cut.

Crews for genres such as news and sports need to share material; it is the only way to meet deadlines and to turn content around in minutes. Both news and sports need to create short packages explaining the event, and do so at a pace described as “near live.”

The NLE changed it all

Collaboration with the flickering window of a film editor was not easy. With videotape editing, several people could sit in the edit bay and watch the job unfold. It came de rigueur for the clients to sit at the back on black leather sofas consuming gourmet snacks while the editor hammered away at the keyboard.

The development of the NLE introduced a step change. Not only could several people follow the process of the edit, but others could also share the source media, maybe for a different version. In the newsroom, a journalist could be cutting a story for the 6 o’clock news while a craft editor could be creating an in-depth piece for later in the evening from the same material, and all without dubbing tapes.

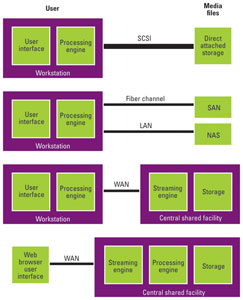

Most NLEs were originally designed for the single user with direct attached storage. Ten years ago, it was common to move jobs between edit bays on hard drives. However, the demands of the newsroom drove the need for the development of shared storage.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The evolution of technologies such as fiber channel, NAS and SAN opened the way to use of a central pool of storage. Users could collaborate, sharing access to content in the pool.

News producers immediately saw the benefit of shared storage, with sports producers and any other genre with the need for fast-turnaround editing, following in their wake.

Avid has been very much at the forefront of providing a platform for collaboration, with Interplay and ISIS (formerly Unity). In the news arena, Quantel, Grass Valley (Edius and K2) and Harris Broadcast (Nexio and Velocity) all have systems.

Apple, with Final Cut, has relied on third-party DAM and storage partners, and as Final Cut Pro transitions from 7 to X, there is no indication from the company that it will enter the professional market with enterprise applications that would support collaboration. That is left for third parties.

Which leaves Adobe. It has recently introduced a collaboration platform called Adobe Anywhere to partner Premiere, Prelude and After Effects.

There are many other ways to implement a collaborative post-production workflow. Your favored NLE can be integrated with any number of third-party applications for asset management and shared storage. Some are aimed solely at the newsroom market, others at post production.

Collaboration

Any newsroom built today will have shared storage as a matter of course, but the availability of better connections between the reporter in the field and the newsroom has raised the question, “Can collaboration happen across the Internet?” As metropolitan areas gain more Wi-Fi hotspots and 4G cellular rolls out, being connected has never been easier. DSNG technology evolves with smaller terminals such as VSAT and broadband global area network (BGAN). (VSAT uses dishes around 1m diameter. BGAN uses a laptop-sized antenna.)

Avid Sphere, Adobe Anywhere and Quantel QTube all offer different methods to support remote editing. Forbidden Technologies offers an alternative to the traditional craft edit vendors with FORscene. Initially developed as a means of remotely logging and rough cuts, FORscene software-as-a-service now supports simple transitions and graphics such as lower thirds — sufficient for most news and much sports content. The camera files are uploaded to the Forbidden cloud and rendered to the final cut for delivery to the newsroom.

Remote editing is built into some newsroom systems. As an example, Dalet has the Onecut editor, a component in its media asset management for news and sports production.

Remote newsgathering

Ideally, a reporter in the field would be able to cut locally shot content as well as browse the news archive back at base for material to show the story in context. The extra material could be cut into the story, which would then be uploaded to the newsroom.

Logistically, it would be good if the reporter could cut the story in a browser and then upload it in the shortest possible time using minimal bandwidth.

For newsgathering organizations, the thin client or Web browser has attractions. A basic laptop can be used by reporters, with no need for the latest, more powerful and expensive laptops for editing in the field.

Whatever the software, the reporter will need to upload clips shot at the scene, and available bandwidth will limit what can be achieved. (See Figure 1.)

Proxy video

Since the days of VHS offline, it has been conventional to make a rough cut with lower resolution or proxy video. The resulting EDL is exported to the online to autoconform the broadcast-resolution video. The proxy is linked to the original media files through tape numbers and time code.

In the days of SD, codecs such as DV25 made it possible to rough cut offline the same video as the final “online” cut. With HD, codecs such as 50Mb/s XDCAM similarly allow one resolution to be used throughout the process, with no need for proxy video.

Figure 1. Editing architecture is constrained by system bandwidth.

When programs are finished at higher bandwidths, such as Avid DNxHD 220 or Apple ProRes 422, the workflows can benefit from the use of proxies such as DNxHD 36 or ProRes 422 (Proxy). The smaller files can be transferred faster with less load on the network and storage. An added benefit is the reduced cost of hardware platforms and infrastructure.

Managing the proxies

The drawback is the need to maintain the proxy and broadcast-resolution files in step. This requires some form of clip and file management, possibly with digital asset management. Quantel developed a technology called Frame Magic that details each video frame with a unique identifier. In conjunction with its virtual file system and Microsoft Smooth Streaming, QTube provides a platform to support globally networked editing.

The old offline workflow was limited by tape as a medium. Now that files are the norm as the medium for clips, the many manual processes of creating proxies and manually tracking clips with tape numbers, then the EDL and conform process are a thing of the past. Proxies can be generated automatically at the file ingest stage, and DAM or similar can maintain the associations between the different resolutions of a clip. The detail of this varies between software vendors.

Avid’s Interplay Sphere adds support for remote editing to Interplay Production asset management. Sphere uses H.264 proxies, with background exchange of high-resolution files as appropriate to the edit.

No proxies?

Are proxies the only route? The answer is no. Adobe Anywhere uses a live render of the broadcast-resolution files and streams a viewing file to the program and source monitor windows. The Mercury engine renders the view at a bit rate suitable for the available bandwidth. The central engine is linked to third-party storage, with the principle being that only one copy of a media clip exists, so anyone viewing the clip, whether from a Premiere editing workstation or previewing from an iPad, sees the same version of the media. (See Figure 1.)

Remote sports production

Remote access to a production archive can be turned back to front. Rather than personnel in the field accessing material back at base, if the base staff can access remote material, then more of the production can be undertaken back at base. This can lead to cost savings by reducing the number of production staff necessary at the event. This is becoming popular for large events, like the Olympics, where minimizing staff at the events has led to considerable savings.

The technical implementation again relies on proxies. The staff at the base location can view material as it is ingested, and review and select clips to be uploaded from the venue at broadcast resolution. This ability to preselect clips remotely makes for efficient use of available bandwidth from the venue.

This method allows production personnel to make use of iso recordings rather than just the output of the production switcher for the primary live transmission feed. With major events using 24 or more cameras, much of the camera output is effectively discarded. A typical major sporting event could possibly feed many different outlets beyond the main transmission feed. The league may well have its own website to provide fans with more complete coverage of a game. The teams could want more coverage for post-match analysis, as could broadcasters in sports round-up programs. The many social media outlets and OTT publishers may also want different cuts of a game. Sports rights will also dictate who can see what. EVS has developed its C-Cast second screen application as Xplore, to support just such workflows.

More can be done with sports events, as the connecting pipe is generally larger. News may rely on satellite for backhaul, or even a 4G cellular connection, whereas most sports venues today should have fiber connections.

Summary

New technologies are freeing the NLE workstation from direct attached storage or the local storage array. Editing can be local or globally remote from the high-resolution files. Vendors have adopted different ways to implement their systems, but inevitably the intervening pipe limits performance. Clever use of proxy files, proxy streams and live renders allow editors to preview, rough cut or perform a full edit on remote material.

It is not just news and sports that benefit. Any production can benefit from collaborating over long distances. It is not just editing that these technologies support, but general review and approval, as well as shot selection and logging. Whether it is an executive producer wanting to view rough cuts at a hotel room edit bay near the set, or a production based across continents, global networked collaboration can save reworks and reshoots by allowing everyone to be involved at all stages of production.

Remote editing saves costs, and provides newsrooms and sports producers more flexibility in how they assemble their programs from the live footage. As fiber and cellular capacity expand, remote editing will only get easier.

—David Austerberry is editor, Broadcast Engineering World edition.