Last Lone Wolf CRT Rebuilder Closing

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Hawk-Eye Picture Tube Manufacturing company has operated from this building in downtown Des Moines since 1991. Its owner plans to end operations this summer.

DES MOINES, IOWA

Scott Avitt swims several miles a week, frequently runs several miles before dawn, and is an ironman tri-athlete. And he's also one of the last players still standing in another field—cathode ray tube rebuilding.

Avitt, 57, has been rebuilding picture tubes since he was 17, following in the footsteps of his father, Frank, who founded the Hawk-Eye Picture Tube Manufacturing business here in 1958. Avitt took over the corporate reins in 1976, and to this day continues to make new CRTs out of old, but not for much longer. The migration to flat screen video displays that accompanied this country's shift to digital broadcasting, coupled with the public's "don't fix it; dump it" attitude has spelled the death knell for this 52 year-old business.

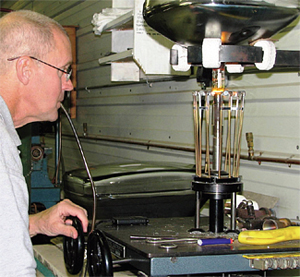

Scott Avitt applies the output coil from a large RF heater to a freshly rebuild CRT. The heat produced will “fire” the tube’s getter, depositing a silvery chemical compound on the neck that traps any gases or water vapor remaining after the tube has been sealed off from the vacuum pumps. Avitt has seen them all—round tubes, ultra-rectangular, glass/metal envelopes, delta guns, in-line guns and bonded yokes. Virtually every type of CRT that has been produced in America or the Far East has found its way into this tidy shop here in Iowa's capital, and Scott, his father, or late brother Alan, found a way to take them apart, replace the worn parts and put them back together as good as, or better, than new.

Hawk-eye has been known to the broadcast crowd for several decades, providing a budget-friendly alternative to factory replacement tubes for Sony, Tektronix, Barco, Conrac, Ikegami and other broadcast lines. (In many cases, the company has been the only source of replacement CRTs for monitors that were orphaned by their manufacturers; literally bringing the dead back to life.)

MAJOR SHIFT

In addition to being a skilled technician who enjoys his work, Avitt is also a businessman and has seen the handwriting on the wall.

"Business really began to slump in 2009 due to all of the flat screen sales," Avitt said. "Before that, we used to average three tubes a day, five days a week. Now it's down to just a trickle."

A new electron gun is sealed onto a small cathode ray tube. Avitt uses his breath to provide the small amount of air pressure necessary to keep the soft glass from collapsing. With home viewers and broadcasters both turning their backs on cathode ray displays, Avitt has decided that it's time to turn the bakeout ovens off for good and retire the vacuum pumps that have characterized his rather unique trade.

At one time, the United States boasted hundreds of CRT rebuilding operations. They existed both in the big cities and in small towns, filling an important niche in making it easier for John and Jane Public to "stay tuned" when the most expensive component in their television sets failed. Typically, a CRT could be rebuilt and sold for one-half to two-thirds of the cost of an all-new tube. Avitt and many others in his trade did their jobs so well, that there was no distinguishable difference between the new and rebuilt CRTs. They even carried the same warranties.

"At out peak—between 1965 and 1971—we kept five employees busy," Avitt said. "We did it all then—even constructing the replacement electron guns and re-phosphoring and aluminizing screens. Our revenue was around $390,000 a year. Collectively, rebuilding was a multi-million dollar business."

Avitt reflected that this all began to change beginning in the 1980s when the "throwaway society" mindset began to kick in.

CRTs: Demand is declining, but king kinescope's reign isn't over yet

While Avitt's Hawk-Eye operation is the last of the small independent CRT rebuilding businesses, there are at least two other U.S. companies that can rework cathode ray tubes—Video Display Corp. and Quest International. Both are fairly large companies in comparison to Hawk-Eye, neither rebuilds "garden variety" CRTs any longer, and both are sufficiently diversified so that they will continue to operate when the demand for CRTs disappears completely. Video Display has several operating divisions, and one of these is Southwest Vacuum Devices, which makes the replacement electron guns that Hawk-Eye has depended upon for some time. Bob Wolfkiel, general manager of the Southwest Vacuum operation says that constructing electron guns for home entertainment purposes is a declining part of their business.

Technicians at Quest International continue to rebuild specialty CRTs. Photo by Quest International "We don't see much business in the consumer-type replacement guns in our product line," Wolfkiel said. "And no one else is building electron guns for consumer CRTs in the U.S. anymore. However, we're still doing a lot of business in specialty tube types—tubes for military applications."

Wolfkiel's words are echoed by Shawn Arshadi, president and co-founder of Irvine, Calif.-based Quest International.

"We do remanufacture CRTs, but not for consumer products," said Arshadi. "That business has been gone for quite a while. We started out in 1998 by rebuilding CRTs for consumer television sets, but branched out to special purpose technologies—medical and industrial monitors, and special displays for flight simulators."

Arshadi said that a large part now of his company's business is in the area of replacing CRT displays in high-end and expensive devices, especially those used in the medical field, with newer display technologies.

"We still get calls from TV stations—mostly those outside the U.S.—about tubes for Conrac, Panasonic, Ikegami, and Asaca-Shibasoku monitors," Arshadi said. "However, most of our business is elsewhere; CRT rebuilding accounts for only about 20 percent. We've branched out in areas such as teleradiology, retrofitting high-end medical monitors from companies like GE, Philips, and Siemens with LCDs."

James O'Neal "The smaller rebuilders started going under in the 70s and 80s," Avitt said. "My brother made a pitch to get broadcasters' business by sending out a brochure listing the broadcast gear that we could rebuild tubes for. That brought us a lot of new business."

DIVERSIFYING THE BUSINESS

Hawk-Eye also went after other markets that were opening up then—bowling alley score displays, coin-operated amusement machines, and even keeping Toys "R" Us supplied with specialty CRTs. Avitt recalls working double shifts and dozing on a lounge chair in between operations to be able to handle the volume. The company expanded into its present 5,500 square foot building in 1991.

However, other rebuilding operations ceased to exist as television got closer to the 21st century—with even the big operations such as Channel Master, Sylvania, Philco and RCA winking out of existence.

Now it's Hawk-Eye's turn.

Even after 40 years of putting in 12-hour days that begin at 4:00 a,m,, Avitt still enjoys his work, but is reconciled to moving on.

He's currently working part-time as an athletic trainer and coach, and will move into this field on a fulltime basis later this summer when he's finished up the last of the standing rebuild orders (now mostly from TV collectors who want to keep their vintage sets alive). After the last CRT is regunned and processed, Avitt plans to donate his tube rebuilding equipment to the Early Television Museum in Ohio, and has volunteered to instruct others in its operation if there's sufficient interest.

"I'm really going to miss rebuilding tubes, though," he said.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.