IP-ENG’s Success Relies on Signal Strength

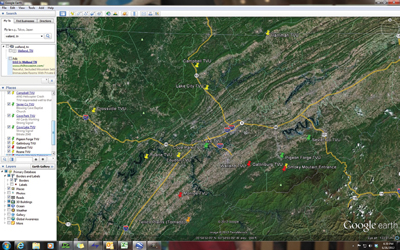

WVLT -TV’s Keith Smith’s Google Map of prime signal quality.

SEATTLE: The growing popularity of portable, IP-based live shot gear that utilizes cell phone network bandwidth, comes as no surprise, because it’s a great equalizer.

“It gives us the ability to do remote television broadcasts, something that used to be the domain of just the television networks and their affiliates,” said Glen Johnson, politics editor for Boston.com, the Web site of The “Boston Globe.”

Johnson was able to roll into town for the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary with the ability to go live, just like the big boys. “You can put the gear in the aircraft overhead, carry it off with you and be remote from that box.” It’s proven to be “very popular with our readers, our viewers, our subscribers. This is a great thing.”

‘ACHILLES HEEL’

Still, live shots via cellphone circuits is not without its headaches. “The Achilles heel to the whole thing is the strength of the cell connections, and so if you’re in an excessively remote location, you might not have bandwidth or signal strength to broadcast,” Johnson said. “That’s why a lot of these product makers build redundancy into their kits, and use different network air cards to try to provide a range of ability to get signals to where you are.”

Boston.com uses the AirStream by Vislink’s LiveGear brand.

Keith Smith, chief photographer at WVLT- TV, the CBS affiliate in Knoxville, Tenn., emphasized the importance of hunting cell phone signal strength. “We’re always checking to see what towers are in the area, where the towers are and how close they are to our location.”

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The process has resulted in a growing body of knowledge. “We keep a database of all of our shots, so I know where we’ve done something in that area before, and I’ve logged it on Google Earth, with details about how the signal strength was, what the quality looked like.”

Just like trying to maintain a good cellphone call, Smith said sometimes a few feet in either direction matters. “If I see that the signal out there could be a little bit better, I’ll tell my guys to walk a few feet in one direction, or a few feet in the other, to find where that very sweet spot is for the cell service.”

WVLT-TV is a TVU Networks customer.

RESISTANCE IS FUTILE

Aaron Ramey, news director at WBND-LP, said ENG crews first need to embrace [cellular bandwidth] technology. The South Bend, Ind.-based ABC affiliate has been doing newscasts for just over a year, and “we have used this gear from day one, so we didn’t have to change habits and change culture in our newsroom,” he said.

“I’ve always equated it to back in the ‘80s, when everybody started purchasing ENG trucks, and you didn’t know what the limitations were until you pushed it. That’s what we’re in the middle of. You’re going to have some failures from time to time.

“We’ve gone to small towns where cell coverage hasn’t been that great, but as the software on the equipment is enhanced, that seems to improve. There are very few places in our market where this thing doesn’t work.”

Pat Middendorf, photographer for WVLT -TV in Knoxville, Tenn., shoots Lauren Davis, anchor/reporter for WVLT -TV on TVU Networks’ TVUPack. Ramey’s portable live shot gear also has WiFi connection capability, and he pointed out the importance of looking for that kind of signal-path backup from a news story scene. “If you’re at a location that has pretty good WiFi, you can connect directly to that. The other thing is, for great quality and response is to try to get a hard line connection to the Internet, which our units are capable of.”

WBND-LP is a LiveU customer.

One hitch in the get-along of cellular networks live shots is signal delay, technically known as latency. WVLT’s Smith said his station runs the portable IP-based gear in two modes.

“If we’re doing a standard live shot, we’re going for quality and not for latency, we average about a five second delay,” Smith said. “If I know—and usually they’ll tell me ahead of time—that we’re less worried about quality, we want the latency to be lower, I’ll set it [for minimum] latency.” That reduces delay down to about two seconds, which results in a smoother back and forth between anchors in the studio and reporter in the field.

A characteristic of live shots utilizing cellular phone circuits is that that a station is not only competing for bandwidth with other stations doing live shots, but also with the general public who may be snapping pictures and transmitting them back to Aunt Emily. WBND’s Ramey recalled an experience at a Notre Dame football game:

“We did an hour special ahead of that ABC game, and our reporter was live on the field at the top of the show, when the stadium was virtually empty. By the end of the show, as the stadium was filling up, we ended up losing the live shot because of that.” But he said he’s found that, in general, “if you can get connected to the cell circuits, more likely than not you’re going to be able to maintain that as long as you stay connected to it.”

WBND’s Smith said getting the cellular liveshot link established early seems to be the ticket to success. For a University of Tennessee game against Georgia, “we got on the towers early, probably about 20 minutes before the game ended, so we already had our IP address.” The link stayed up fine.

Like any new technology, cellular networks live-shot gear has its own peculiarities, its own learning curve. All three individuals TV Technology spoke with are high on the capabilities and portability of the equipment, and predict the continued build-out of 4G cell phone infrastructure will enhance the success of their live shots.