HDR: Simply Better Pixels

Maybe too much better?

Sure, HDR (aka high dynamic range) is better than SDR (standard dynamic range, a term we didn’t even need until we had HDR), but why?

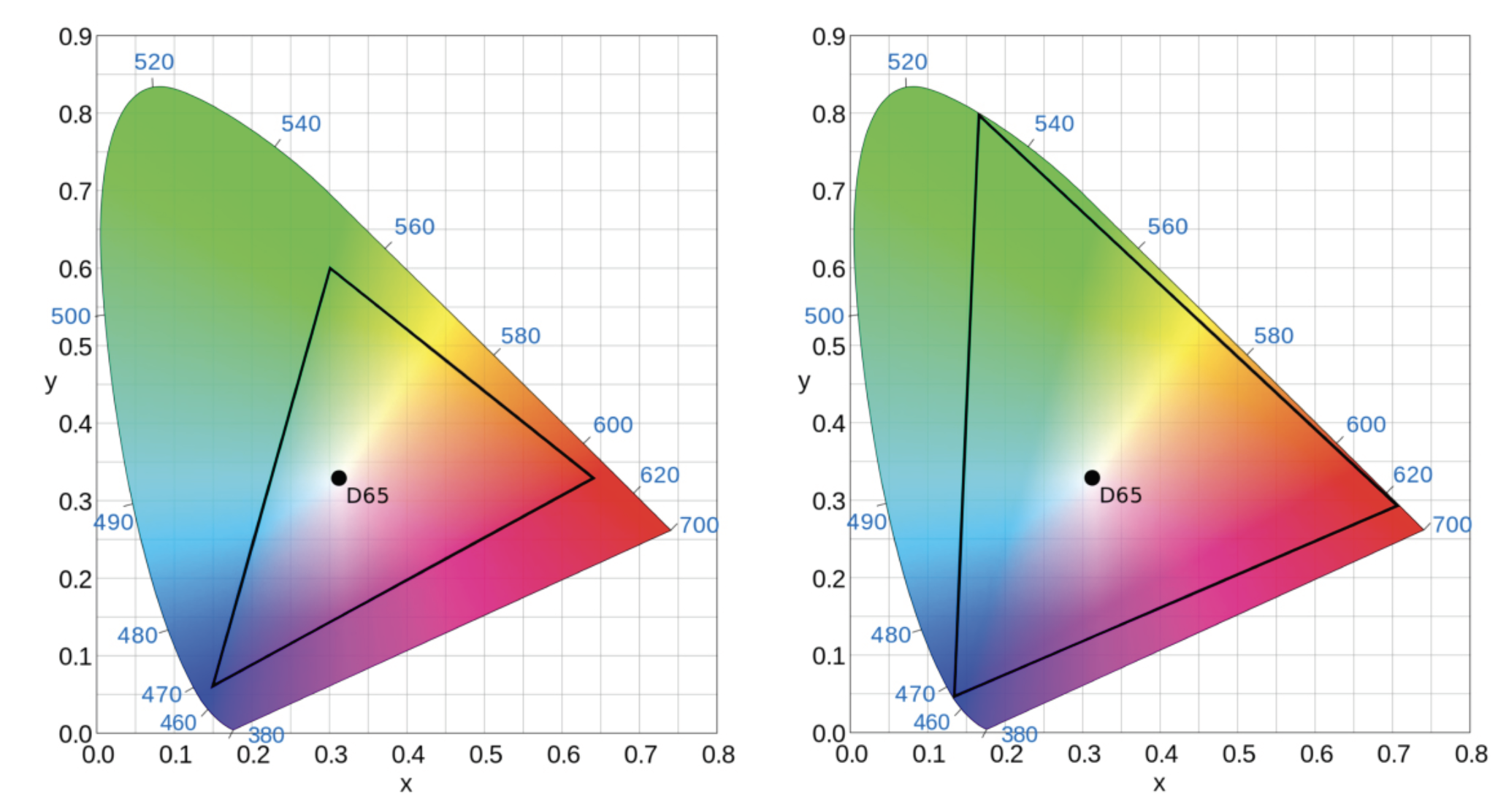

SDR is regular television—it can produce a maximum luminance level of around 100 nits limited to Rec.709. HDR gives a maximum luminance of 1,000 to 10,000 nits (and a minimum of 400 nits), with brighter brights, more detailed darks and more saturated colors with Rec, 2020 (Fig 1). The more realistic color is due more to WCG (wide color gamut) than to HDR itself.

Three Formats

There are three main display formats for HDR: HDR10, HDR10+ and Dolby Vision. As you would expect, each handles HDR differently.

HDR10 is open standard, typically mastered between 400 to 4,000 nits. It’s a PQ (perceptual quantizer) transfer function with static metadata, delivering the same brightness and tone mapping for the entire program.

HDR10+ is royalty-free for the content creator. TV/display manufacturers pay an annual license fee. Dolby Vision, similar to HDR10+, is proprietary from Dolby Laboratories. Both are mastered from 1,000 to 4,000 nits using dynamic metadata that adjusts the brightness and tone mapping per scene.

For HDR10+ and Dolby Vision, most content is mastered at around 1,000 nits. While seemingly the same, Dolby Vision is considered better than HDR10+ in areas such as peak brightness minimum, tone mapping, TV support and content availability, according to a number of sources.

Stretching the Truth

Marketing & PR are one-half truth, one-half half-truths and one half omitting the truth—it all depends on what’s being sold. But sometimes, the people doing the selling don’t really understand what they’re selling.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

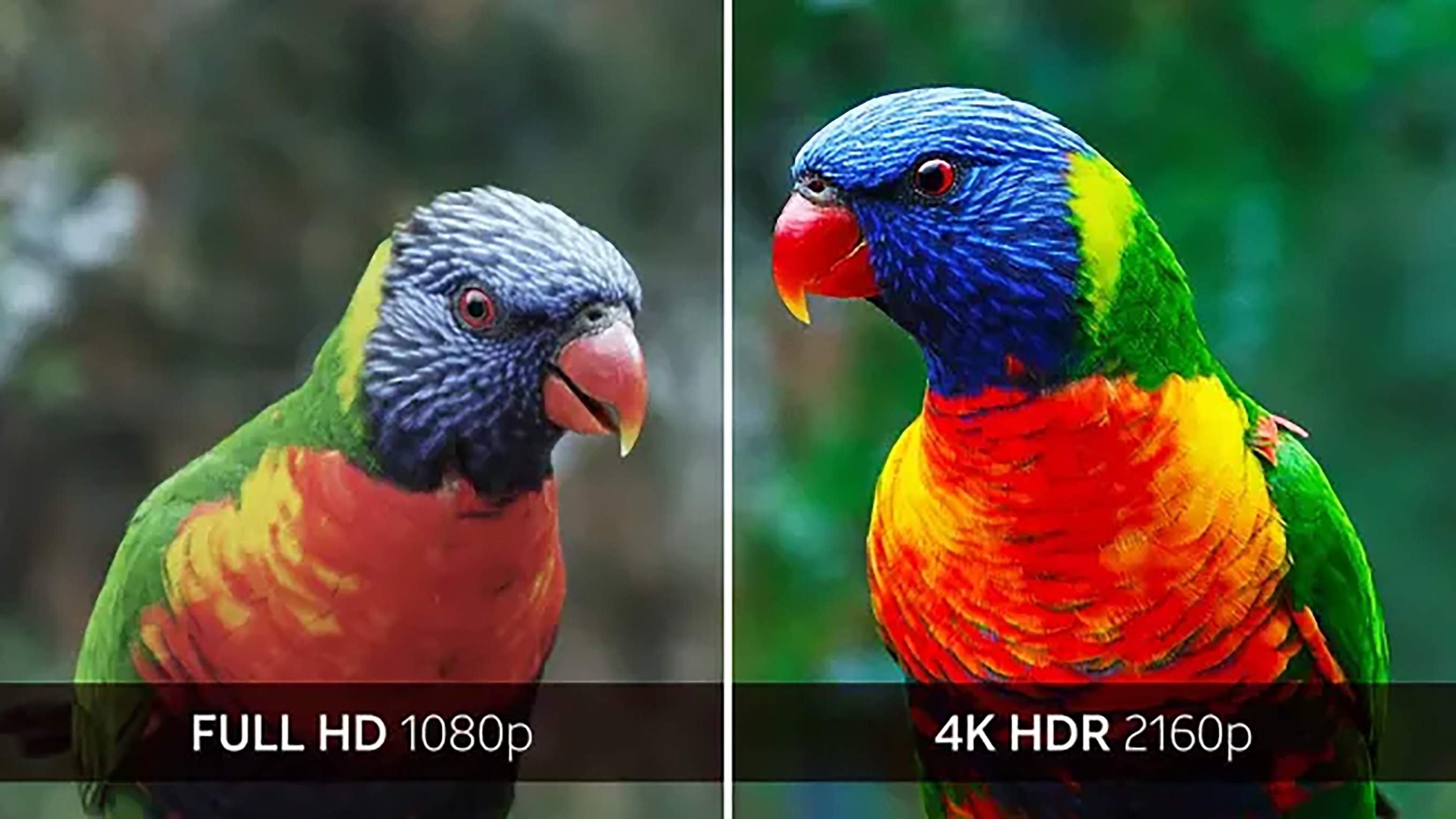

In a recent “Consumer Reports”’ story, “How to Watch Super Bowl LVII in 4K HDR,” buried deep in the story, there’s an image appearing to be from DirecTV to promote 4K HDR, comparing two images of a colorful parrot to show the better quality of “4K

HDR 2160p.” (Fig. 2)

But that image is being compared to “Full HD 1080p”—not exactly an apples-to-apples comparison with only one image being HDR. The message is clear: This is how great the Super Bowl will look, compared to your old fashioned 1080p SDR TV, if you can get it in 4K. But if the 1080p image had HDR, the difference wouldn’t be so… different.

Do We Really Need 4K if HDR is So Good?

SMPTE Life Fellow Mark Schubin has compared formats, frame rates and HDR to show what provided the best data option.

“HDR offers the most bang for the bit,” Schubin said. Preliminary HDR data that he presented at the annual HPA Tech Retreat in 2016 from EPFL (École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne/Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne) from 2014 showed a “tremendous improvement and very, very little additional bits required, anything from zero to maybe something around 20%.”

That improvement was in peak brightness. Schubin compared it to EBU quality comparisons from 2013 between HD (720p, 1080i and 1080p) and 4K showing “very little improvement” in quality, as well as high frame rates up to 240Hz, which showed “a significant improvement [in quality], but you also have to double the bitrate for every doubling of the framerate.”

The greater brightness and contrast range of HDR is key. “What makes it more realistic is the human visual system because we perceive more contrast as spatial resolution,” said Matthew Goldman, senior director, Media Engineering & Architecture for Sinclair Broadcast Group. “It looks more real.”

Returning to Fox’s Super Bowl 4K upconversion, I asked Schubin: “What is

your opinion of the viewer’s quality difference between 1080p60 HDR and 2160p60 HDR on a 4K TV that would upconvert the 1080p

to 2160p?”

“Without knowing the specific equipment involved, I really can’t say which is better, but I’d say the difference is probably negligible,” Schubin said. “It’s not clear that Fox’s technology would necessarily be better than what’s in a TV. Yes, it costs more, but the TV stuff is integrated and amortized over tens of millions of sets. But the production in HLG could be significant.

“When HDR has been perceived as problematic—such as the very dark ‘Game of Thrones’—the production has not been HLG,” he added. “In the dark areas, HLG is essentially the same as SDR; it’s in the bright areas that it offers much more range, so it’s probably good to use for the live

Super Bowl.”

Schubin didn’t watch this year’s Super Bowl in HDR, but added: “Having watched football in HLG HDR, I think it offers a substantial advantage, visible even on a small screen from across the room. Having watched football in HD, upconverted to 4K, and true 4K, on side-by-side monitors, I’d say differences are perceptible, but just barely—definitely not the big kick added by HDR.”

More Comparisons

1080p HDR, upconverted 4K HDR or native 4K HDR: which is better?

What do you mean by “better?”

Tim Walker, senior product manager (HDR image analyzers, frame syncs, routers, scaling and scan converters), at AJA Video Systems, puts it this way: “There’s broadcasters that are being bullish doing and promoting HDR,” he said. “Others question the extra expense in producing HDR. But for a top-end broadcaster, you’re investing in your archive for generations to come from the moments captured today.”

That means producing the best possible imagery today: 4K HDR.

“Doing [less expensive] upconversion at distribution gets you that 4K banner,” Walker added. Upconverters do an exceptional job—that’s one reason people do 1080p HDR and not worry about 4K in the truck.”

Walker, Goldman and Schubin are firmly in the “better pixels, not more pixels” camp.

“Having HDR makes for a better viewing experience from home,” said Walker. “Plus, you can absolutely see a benefit of down-mapping or tone-mapping to SDR. Viewers benefit from the entire signal processing chain using HDR. In live sports, you won’t get the highlights off the helmets, but you will get more detail in the image in the darks and brights. SDR will benefit from a native HDR production.”

Then There's Sinclair

Sinclair is doing HDR 24/7 with ATSC 3.0 over the air broadcasts in more than 30 markets nationwide (and growing).

“We absolutely see it as a business advantage at the end of the day, improving the viewing experience of our viewers,” said Goldman. ”Other than sports, it just looks more realistic—the screen pops. You don’t know you’re missing it until you’ve got it. All I have to do is show it to you. Consumers may not know what HDR is, but they know they like it, so there’s definitely a commercial advantage.”

What makes Sinclair unique is the HDR they’re using is not HDR10. “We’re using part of the ATSC 3.0 standard, A/341, and use Advanced HDR by Technicolor [SL-HDR1], as a transmission format,” said Goldman. “It’s not a new HDR format. What SL-HDR1 lets us do is send SDR video as a base layer plus an enhancement layer for HDR as part of the metadata stream.

“The reason we do this is that it doesn’t matter how you get to the TV, it’ll display a useable picture,” Goldman added. “It’ll do great SDR—and with the SL-HDR1 metadata reconstruction—HDR with the SDR video without having to rely on the TV. We guarantee that the original artistic intent is maintained for both SDR and HDR.”

Every HDR TV uses HDMI with EDID (Extended Display Identification Data)—that’s part of the handshake between the TV and the signal device. But what are the capabilities of the display? Is it HDR? What formats? What’s the minimum light level, peak white level, colorimetry? The HDR is then adapted for that display. If it’s SDR only, that’s all it gets. Sinclair uses SL-HDR1 because, according to Goldman, it’s the only transport format that’s TV set-independent and delivers a useable picture.

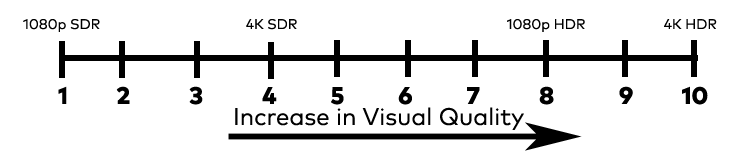

I asked both Goldman from Sinclair and Walker from AJA the same visual quality question: With all things being equal, on a scale from 1 to 10, if 1080p SDR is a 1 and 4K HDR is a 10, where would you place 1080p HDR and 4K SDR?

Both answered exactly the same: 1080p HDR sits at 8, while 4K SDR sits at 4 (Fig. 3).

That’s the power of HDR, but it doesn’t negate shooting to archive in 4K HDR. The question is: How do you want your production perceived by viewers today… and in the years to come?

Michael Silbergleid serves as president of Silverknight Consulting in Fort Myers, FL, a strategic communications firm serving the broadcast and media industries since 1999. Previously, he was editor of Television

Broadcast magazine and Sports TV Production, the first sports-dedicated trade magazine for the industry. He was manager of Educational Television and Telecommunication Engineering for the Huntsville City

School System in Alabama and has been a producer, director, video editor, chief engineer and facility designer. He holds an MA degree in Telecommunication and Film Management from the University of Alabama,

and two BA degrees in Dramatic Arts & Dance and in Speech Communications from SUNY Geneseo.