Graphics for 3DTV: Are We There Yet?

OTTAWA: TV graphics designers have been rendering 3D graphics for 2D TV (HD and SD) for years. Typically, the 3D graphics are created inside a virtual 3D world in their computers. These 3D images are then converted so that they still appear to be three-dimensional when viewed on a 2D TV screen.

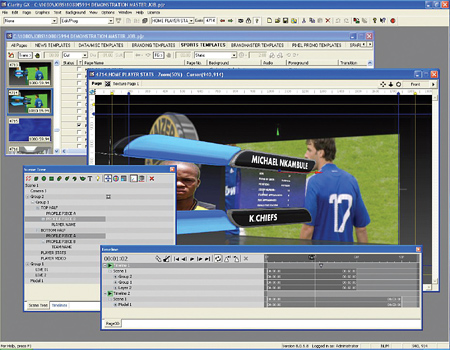

Pixel Power's 3D stereographic option is seamlessly integrated within Pixel Power Clarity and BrandMaster interfaces. "3D graphics and animation capabilities are a standard feature on Chyron's two-channel HyperX3 on-air graphics systems, and since most of the graphics are already designed in 3D, broadcasters can take them to air even more quickly," says Jim Martinolich, Chyron's vice president of Integration Technology for Chyron in Melville, NY. "Some tricks, such as shading the area around a lower third or logo, help to blend the graphics into the 3D scene."

Logically, using 3D graphics on 3DTV should be simpler than working with 2D television, because no conversion is required. A designer should be able to import their 3D renderings directly into the 3D playout server, for overlaying with 3D video as required.

In the strictest sense, this assumption is correct. However, actually mixing 3D graphics and live 3D video can be downright tricky, if not sometimes seemingly impossible.

ESPN: LESSONS LEARNED

With over 170 3D sports telecasts to its credit, ESPN knows a lot about live 3DTV broadcasting. That's not all: As a regular user of 3D graphics products made by Vizrt and Pixel Power (Brandmaster), ESPN knows a great deal about the conflicts that can occur between 3D graphics and 3D video.

"The biggest challenge lies in depth of field," says Robert Toms, ESPN's vice president of Production Enhancement and Creative Services. "For a 3D graphic to look good on top of 3D live video, the depth of field has to be the same. So if the shot shows a clear wide shot with a long depth of field, the graphics have to match that look.

"Similarly, if we are going tight on a close shot with a very shallow depth of field, the graphics have to match that," he added. "If they don't match, the visual result is jarring to the viewer. Their heads can literally hurt, as their brains try to integrate the conflicting depths of field."

The depth of field conflict is most widely pronounced when ESPN uses "lower third" graphics to display team names, scores and other information. In doing so, the network is following a 2D tradition: The lower third of the screen has been reserved for these kinds of graphics for decades.

"The lower third section of the screen is typically the area that is closest to the viewer," says Toms. "This is also where things can change the most; for instance, if someone walks through the shot close to the camera. Now in 2D, this isn't an issue, but in 3D it can be a nightmare.

"The viewer is looking at the lower third graphics in the foreground—because that's where they sit on the screen—and out of nowhere a cheerleader suddenly walks in front of them!" Toms continued. "As much as the viewer might welcome seeing the cheerleader, the visual confusion this causes is hard to take."

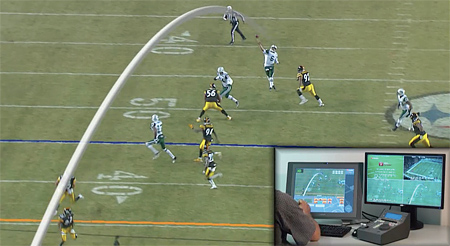

Sportscasters use Vizrt's LiberoVision software to analyze plays. In contrast, the upper third of the screen tends to stay stable in 3D, which is why ESPN is considering moving its team/score graphics up to this space. Doing so will require camera angles to be adjusted, so that this landscape is freed up during live play. But it would solve the problem of foreground interference.

"Depth of field issues have also made it hard to properly place time clocks," Toms said. "We are now looking at a design where the clock is rendered so that it appears to be part of the viewer's TV bezel."

GOOD NEWS FOR BROADCASTERS

ESPN's trail-blazing efforts in 3D graphics on 3DTV will make life easier for other broadcasters. Eventually they will want to consider occasional 3D broadcasts, simply because 3D capability is now being included on high-end HDTV sets, and will likely become available on inexpensive TVs as the years progress.

When it does become worthwhile for broadcasters to offer 3D extravaganzas, chances are that their graphics suites will be ready to cope. For instance, "our Clarity 3000 and Brandmaster already render inside a virtual 3D world, so getting this product into the 3DTV world simply requires a few small adjustments and a second video stream," says Pete Challinger, CEO of Pixel Power in Burbank, Calif. "Really, all that is needed is a second 'eye' in the 3D rendering system, to capture the second view such that the two combined will look three-dimensional when seen on a 3DTV set."

According to David Jorba, senior vice president of Vizrt America, converting Viz graphics to 3D stereoscopic is as easy as clicking on a button. "However, we have learned that 3D productions require the designer to be aware of a number of parameters that were not there before," he said. "Depth of field is one; becoming smart on how and where and when to place the graphics is just as important."

As well, Jorba wants to see tighter integration between 3D graphics software and 3D camera settings, so that the right hand knows what the left hand is doing. "Knowing the 3D position of the camera as we switch to different graphics will allow for seamless transitions from one 3D graphic to another," he says.

As for the 'depth of field' issue? Orad's 3DPlay graphics suite addresses it by letting designers choose between 256 depth of field positions in 3D; ranging from back in the distance to right up front. 3DPlay can even be programmed to automatically adjust the depth of field as the director switches from one camera to another.

"What we do in advance of actually shooting is to understand basically the depth of field of each camera, and how it is to be used," says Shaun Dail, Orad's vice president of sales and marketing, North America. "When a camera switch is made, that data is automatically relayed to the 3DPlay unit, and the graphics' depth is field is adjusted."

In the meantime, ESPN will continue to soldier on, exploring the brave new world of 3D graphics on live 3DTV. "It's still a learning curve for us," says Toms. "We are still learning what works, and what doesn't."

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

James Careless is an award-winning journalist who has written for TV Technology since the 1990s. He has covered HDTV from the days of the six competing HDTV formats that led to the 1993 Grand Alliance, and onwards through ATSC 3.0 and OTT. He also writes for Radio World, along with other publications in aerospace, defense, public safety, streaming media, plus the amusement park industry for something different.