Gary Shapiro: Championing an Industry

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Gary Shapiro is back home from the World Electronics Forum in New Delhi just days after armed sociopaths unleash terror in Mumbai. Shootings at the New Delhi airport delay his return to Detroit, which despite the ghost-town affect of the failing auto industry, is Elysian compared to India’s capital city.

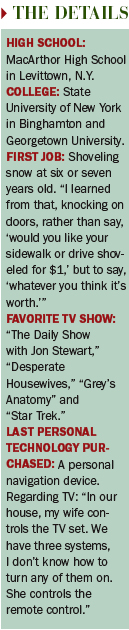

Three days a week, he lives in Detroit where his wife works as a surgeon. The rest of the time, he’s a technology evangelist on Capitol Hill. A fixture, really, after 26 years at the Consumer Electronics Association, which he now runs. Longer still, considering his tenure at a law firm that represented the CEA, where he landed in 1979 at the wizened age of 22.

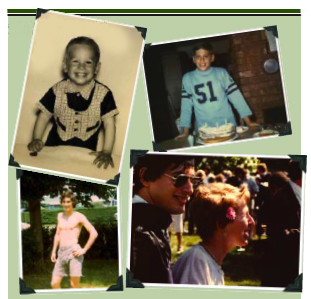

Gary Shapiro travels the world. He plays host to the biggest trade show in the known universe. He didn’t silver spoon his way to becoming a jetsetting power broker. In the ’60s, he’s a scrappy Long Island kid whose dad teaches seventh grade. His mom sells encyclopedias and teaches Hebrew.

“It was not an affluent household,” he says. “My parents bought their house for $7,000.”

Mildred and Jerome Shapiro have four boys. They work. Gary shovels snow, buses tables, mows lawns, delivers newspapers. He figures out early on what he’s not cut out for.

ENLIGHTENMENT

“One of my defining moments came when I was 13 or 14,” Shapiro says. “My brother who was two-and-a-half years older signed up for a temp service, and he got a call. He said to go and say I was him. I went to work putting lamps together and thought, ‘God, I’m going to college, I’m not going to work in a factory.’”

Another time after washing dishes all night, the boss hands Gary a $20 and tells him to come back every night. Young Master Shapiro didn’t think so, thank you very much. He graduates early from high school and goes to college where he starts setting up audio systems and mixing sound for bands.

“I got the job because I was frustrated with how concerts were being run, and because I had a sense of order,” he says. Shapiro eventually lands a gig at the renowned Jones Beach Theater. “Guy Lombardo was playing every night,” he says. “I was managing 100 people at the age of 20.”

He takes an undergrad degree in psychology and economics from SUNY in Binghamton, N.Y., and heads for law school at Georgetown. He joins a Washington, D.C. law firm that defends home video recording in Universal City Studios v. Sony Corp, more commonly known as the Betamax case.

The Supreme Court rules in 1984 that home recording doesn’t constitute copyright infringement. It forges Shapiro’s philosophy that content creation shouldn’t dictate innovations in distribution technology.

Two decades later, he hands a trade reporter a tiny booklet. “Your Pocket Betamax Decision.” These days, Shapiro is a new father again. He’s a hair less wired than he used to be. He doesn’t feel compelled to debate everything. He says.

He’s worked a lot of issues at CEA over the years--HDTV, energy consumption, plug-and-play--some to greater effect than others. His current cause celebre is preserving free trade and preventing unionization by card check instead of secret ballot. This would drive some of his member companies overseas, says the son of a strict Democrat and union organizer. Unions, he believes, led to Detroit’s implosion. His opposition will pit him against the nation’s first digital president. But it’s all good.

“I love to debate,” he says.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.