Seeing Through the Eye of the Fresnel

Jay Holben

The world of lighting hardware can be confusing waters to navigate. There are so many different options, so many different types of fixtures, quality of light and methods of creating light; how do you know which is the right one to use?

To help understand the different types of fixtures and their applications, I’m going to discuss one specific, identified by the type of lens it uses: the Fresnel.

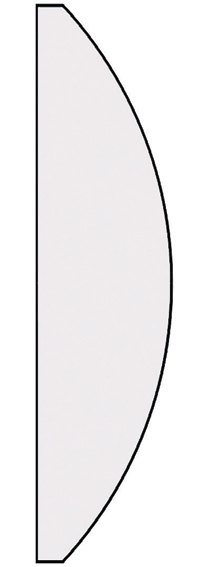

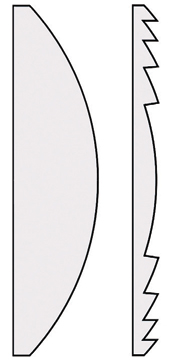

Fig. 1: Plano-convex lens In a fixture without any lens, commonly called “open face,” the light emitted spreads out in all directions, more or less evenly, from the source. Most of the time, this creates a large, uncontrolled and unrefined field of light. A reflector can help to re-direct and focus some of these light rays, but a lens is required to really concentrate the light rays and make the fixture more efficient for controlling the light.

PLANO-CONVEX

One of the most basic types of lenses is the plano-convex lens (Fig. 1). As the name describes, the plano-convex has one flat side (plano) and one convex side. Light passing through the lens refracts considerably, but the direction of the exiting light rays depend on the specific distance to the actual source.

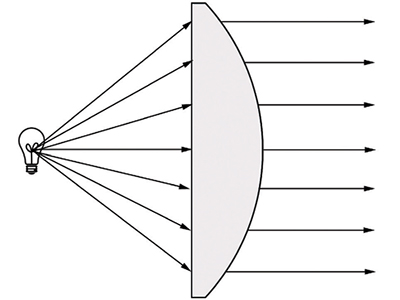

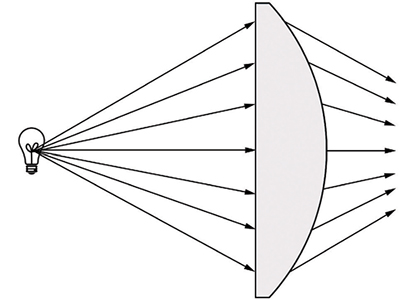

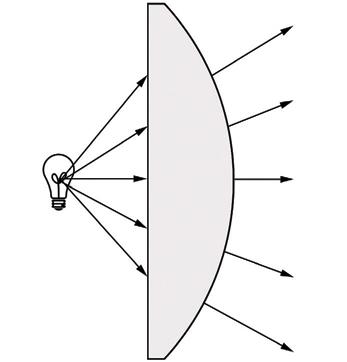

When the source is set at the proper distance to the plano side of the lens, the light rays are refracted and exit from the convex side of the lens in a parallel fashion (Fig. 2). If the source is moved farther away from the lens, the resulting light rays are refracted to converge upon themselves, forming a tight pool of light (Fig 3). If the light source is moved closer to the lens, then the rays diverge, forming a wider pool (Fig. 4). In all three cases, the introduction of a lens forces the light rays into a more efficient and controlled path.

Fig. 2: When the source is set at the proper distance to the plano side of the lens, the light rays are refracted and exit from the convex side of the lens in a parallel fashion. In the early 1800s, French physicist Augustin- Jean Fresnel was working to create a large lens for lighthouses. The challenge with the plano-convex lens was that it was impossible to create a large aperture (diameter) lens for large applications as the amount of glass involved became far too heavy and impossible to work with. By starting with the plano-convex shape and cutting away the mass of the lens in concentric circles, Fresnel determined he could retain the qualities of the lens while greatly reducing its mass (Fig. 5).

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The Fresnel lens was adopted into theatrical and film lighting almost as early as artificial light itself. Relatively lightweight, this workhorse lens allows light to be efficiently utilized in a soft, even field. Fixtures with Fresnel lenses most often have a “flood” and “spot” function on them, which literally moves the lamp and socket inside the fixture further away or closer to the fixed lens. This forces the light rays to converge or diverge, making them into a tight, smaller circle (spot) or a large, wide one (flood). Of course, spotting in a fixture intensifies the brightness of that smaller spot where as flooding (diverging) spreads out the same light rays over a larger area and reduces the overall intensity of the light at a given distance.

Fig. 3: If the source is moved farther away from the lens, the resulting light rays are refracted to converge upon themselves, forming a tight pool of light.Fig. 4: If a light source is moved closer to the plano side of the lens, the rays diverge, forming a wider pool. MANY STILL TO CHOOSE FROM

Mole Richardson, one of the oldest manufacturers of lighting fixtures for the motion picture industry still in operation today, has many Fresnel instruments to choose from, each with a different aperture and lamp wattage—in addition to fun and funky names that have become ubiquitous in the industry—whether or not you’re using a Mole fixture.

Fig. 5: By starting with the plano-convex shape and cutting away the mass of the lens in concentric circles, French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel determined he could retain the qualities of the lens while greatly reducing its mass. In the Mole-Richardson incandescent (tungsten) line, they offer the Midget (200- watt 4 15/32-inch Fresnel lens), Tweenie (650-watt 4 15/32- inch Fresnel), Baby (1,000-watt 6-inch Fresnel), Junior (2,000- watt 9 7/8-inch Fresnel), Senior (5,000-watt 14-inch Fresnel) and Tenner (10,000-watt 24 ¾-inch Fresnel). Even though the “Big- Eye” 10K fixture has a two-foot diameter Fresnel lens, whereas the Midget has a four and a half inch Fresnel, they both refract light the same through their Fresnel lenses. In both cases the lens performs the exact same function, just with widely different intensities (determined by lamp wattage) and sizes of the light beams (determined by size of the lens). Other manufacturers, such as Arri, DeSisti, Litepanels and Altman offer their own line of Fresnel fixtures. Fresnel lenses are also often seen on HMI fixtures, even as an accessory to a PAR (parabolic aluminized reflector) fixture.

The Fresnel offers an even field of light that is considered “pleasing” on the face. It can be used clean (without diffusion) on a person, without creating a harsh or unappealing look. A Fresnel doesn’t have the same “throw” that a spotlight does, meaning the light doesn’t necessarily travel well over great distances, but is more often used closer to talent or subjects. The Fresnel can, of course, be used through diffusion or in a softbox—such as a Chimera softbox—but they aren’t necessarily as efficient behind diffusion or in a softbox as an open-face fixture might be.

Jay Holben is the technical editor of Digital Video and a contributor to Government Video. He is also the author of the book “A Shot in the Dark: A Creative DIY Guide to Digital Video Lighting on (Almost) No Budget.”