'How Did They Get That Lighting Effect?'

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most lighting designers share an unconscious habit. When viewing a striking image of some type—a painting, a scene in a film, a theater piece, a TV moment—the designer will intuitively pose the question, "How was it lighted and what would I do to get that effect?"

This questioning is a great spare-time activity and can provide endless topics of discussion among your peers. I recall many, many years ago taking an exam for the United Scenic Artists that showed a photo of a painting (a sunrise scene, if I remember correctly), and asked how one would go about achieving this effect. The "living pictures" of the famous Pageant of the Masters, held for 80 years in Laguna Beach, Calif., also come to mind.

'REMBRANDT LIGHTING'

Fig. 1: Rembrandt self-portrait I have heard this term bandied about years. So let's start by examining a very famous self-portrait of the artist, (Fig. 1). From the characteristics of shadow areas, it is quite obvious that the source has a large aperture; or, in today's terms, a large "soft light." It is also evident that the background is purposely not a realistic representation of the actual, (remember this is a painting, not a photo).

Two things stand out for me. Conventional, current portrait-lighting purists would dictate that the light come from the right side rather than Rembrandt's choice of the left. Since Rembrandt is not around to defend his choice, we shall leave that be. The second issue is the overall bronze cast of the painting. Although aging and varnish might have contributed to this effect, we have to assume that this warmth, no matter to what degree, was the intent of the artist. Modern-day lighting practitioners who advocate that "warmth" be ever present and, therefore, place a piece of CTO on every lamp, now have another excuse: "If Rembrandt did it, so can I."

MY FAVORITE OLD MASTER

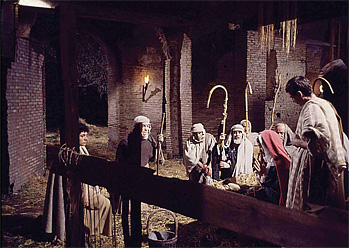

My second illustration is a Nativity scene by El Greco, (Fig. 2), whose astounding paintings in his unique, very modernistic style were amazingly created during the Renaissance in the 16th century. With some hesitation, I contrast El Greco's painting with a photo from the rehearsal of a Nativity reenactment from my archives (Fig.3), done in the 20th century and shot at the archeological site of Ostia Antica, the ancient seaport of Rome. The only similarity that I can see between my reenactment and the brilliance of the Master's painting is that the composition is fitting and the lighting is acceptable under the restraints imposed by a multiple-camera shooting of the scene. The lighted barndoor in the upper left of my production photo is not evident in El Greco's masterpiece.

Fig. 2: Nativity painting by El Greco

Fig. 3: A television Nativity scene

CANDLELIGHT WAS HIS THING

Georges de La Tour (1593-1653) was a French painter known for his numerous nocturnal paintings, in which a single candle was typically the source of lighting and usually masked from direct view, (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: A candlelight painting by Georges de La Tour

Fig. 5: A Carbon filament lamp as a source

There is no question as to de La Tour's "motivation" for the lighting. My version of this scene (Fig. 5), replaces the candle with an old carbon-filament lamp. The lamp itself is not bright enough for exposure and, even if it were, its brightness would overbalance the values of the shot (as it is not masked as George's candles). My viewer is made to believe that the practical light is the source by using an out-of-frame light to create a shadow on the subject that would (approximately) duplicate the shadow from the real lamp. In such cases, the strength of the actor's performance will hopefully distract the viewer from observing that the shadows cast on the doctor's visible arm could not have originated from the prop lamp. Luckily, for the sake of one's reputation, the viewer is rarely this perceptive.

'PASS THE POTATOES, PLEASE'

The very famous "Potato Eaters" painting by Vincent Van Gogh (Fig. 6), shows a gathering of peasants around a table that the great post-impressionist lighted by means of a hanging oil lamp. My comparative example (Fig. 7), is set in more elegant surroundings with a group of well-to-do diners who are probably enjoying Beef Wellington instead of potatoes. I hope you agree that the source in my example is the chandelier which, in case you might miss that fact, has been specifically highlighted so that there is no doubt of its importance. As in the painting, the walls do fall off dramatically, thereby placing the emphasis on the diners. It has been a number of years since I have seen Van Gogh's painting at its home in Amsterdam and cannot recall if it has the overall green cast apparent in the reproduction. I shudder to think what the reaction would be if you tried this effect in a real-life situation. (You would probably be asked to sever your association with the lighting community.)

Fig. 6: “Potato Eaters” by Vincent Van Gogh

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Fig. 7: A modern dinner scene

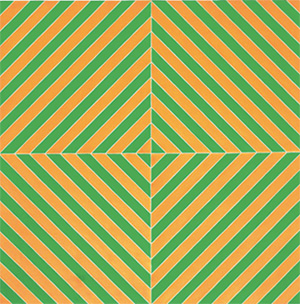

AN EASY ONE

Fig. 8: An abstract painting by Frank Stella The last example is by Frank Stella, the well-known contemporary American abstract and minimalist artist (Fig. 8). According to a biography I read, Frank Stella credits Caravaggio as an influence on his art. Interestingly, Caravaggio greatly influenced de La Tour, as well as Rembrandt, and was known for his very dramatic use of lighting. In the case of this very typical painting by Stella, I find it difficult to detect Caravaggio's influence, but this should not stop us from attempting to recreate the look of the painting with our lighting. In fact, let's join the LED proponents and suggest a complicated compartmentalized light box with LEDs (at last, a use!) in RGBW, of course, and see if we can get that yellow. If it works we can then, with proper acknowledgement to Frank Stella, create all sorts of color combinations and optical illusions using our own artist's palette—the lighting console's effects package.

Bill Klages would like to extend an invitation to all the lighting people out there to give him your thoughts at billklages@roadrunner.com.