The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

NEW YORK—As we observe the 20th anniversary of 9/11 this month, I want to focus on how New York City broadcasters recovered from the tragedy and their eventual move to One World Trade Center. My involvement with other broadcast engineers on the emergency restoration of over-the-air broadcasting at Alpine—with John Lyons at Durst and New York broadcasters on proving the viability of One WTC for TV broadcasting—and with construction of the first station on the air from One World Trade Center were certainly the highlights of my 50-year career in broadcast engineering.

On that morning, I was getting ready to leave my townhouse for my office at Telemundo in Hialeah, Fla. when I got a call about a plane striking the World Trade Center. My first thought was it was a small plane, like one that crashed into it before but after turning on the TV and watching the news it became clear this was worse. Much worse.

When I got to my office, after verifying that Gene Pfeiffer, the transmitter engineer at Telemundo’s WNJU, had been delayed getting to the transmitter site that morning and was safe, I started looking for a site where we could get back on the air. The Alpine Tower in Alpine, N.Y. seemed like the best choice and I soon found out other broadcasters had the same idea.

Charles Sackermann and his engineers at Alpine Tower Company were working on plans to put broadcasters in a building next to the famous tower. I also called vendors to see what equipment was available and determine how quickly they could get it to the site. Remember this was analog TV, so we had waveform monitors, stereo generators, distribution amplifiers, video and audio processing gear and patchbays.

WORKING TOGETHER WITH A SINGLE PURPOSE

I was ready to go to Alpine to help, but travel was difficult as all flights were grounded, and my office seemed like a better place to handle orders, get finance approvals, start FCC filings, and deal with the other paperwork needed to get things moving. As soon as Long Island MacArthur Airport opened, I headed to the site.

When I arrived, what I found was the most amazing band of people—engineers, contractors, manufacturers, electricians, tower crews, plumbers—all working together with a single purpose to get broadcasters back on the air. Just remembering those people and the energy there still chokes me up a bit 20 years later. What made the experience more poignant is that most of the people working at the site had lost friends on 9/11. Getting TV back on the air was one small way to honor those people.

At Alpine, equipment that normally took months to deliver showed up in a week or two. When there wasn’t enough power at the site for all the transmitters, GE—which owned NBC at the time—rolled in generators with UPS in trailers until the utility company could bring in more power. Transmitter manufacturers found transmitters and antenna manufacturers—notably Dielectric—used material they had on hand to fabricate antennas.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Customers in other parts of the country accepted delayed deliveries in order to prioritize getting New York broadcasters back on the air. Telemundo’s station, WNJU, was fortunate because we had an IOT transmitter in storage in Brooklyn that was supposed to have been installed at the World Trade Center. Daily meetings solved problems like where to put the antennas, power availability, how to fit the cooling systems on the roof, and other mundane but necessary issues to make sure the facility performed as well as it could.

Anyone who has built a TV transmission facility knows how long it takes. At Alpine, five stations—WNBC, WABC, WPIX, WNET and WNJU—were back on the air just weeks after the loss of the World Trade Center. WCBS kept a backup facility at the Empire State Building so was able to get back on the air immediately from that location.

EVENTUALLY EMPIRE

Alpine wasn’t the ultimate solution. Returning to the Empire State Building was the best way to restore full coverage, but finding room there for all these stations’ antennas and transmitters wasn’t easy. It involved some creative solutions, like essentially hanging a temporary low VHF panel antenna out a window. The final configuration included some antennas below the mast. WNJU, WPXN and WNYW (Fox) had antennas mounted in between the “wings” below the mooring mast (Fig. 1).

I used CAD drawings of the building to design the analog antenna system for WNJU using a standard wide cardioid slot antenna facing the northeast to cover the major part of the audience and a fill in panel antenna in between the “wings” to cover the southwest. The wings were used to minimize overlap between the two antennas where out of phase signals would cancel. Fortunately the southeast overlap area was mostly over water. Getting the antenna line in place wasn’t easy—it had to go through a shaft which for fire prevention reasons had to be bricked off after the line was run.

Broadcasters had already started broadcasting DTV prior to 9/11 from a broadband panel antenna WNBC installed and there was a desire to get DTV back on the air. For a while, WNBC-DT after 9/11 operated with a 1 kW Comark transmitter and an Andrew AL-8 slot antenna mounted on the roof at 30 Rockefeller Center. WCBS eventually installed a broadband panel antenna at Empire that served five other stations (WNBC, WWOR-TV, WABC-TV, WPIX and WNET).

Due to limited space, this antenna was, at best, a compromise. There wasn’t room for WNJU’s DTV antenna at Empire, so WNJU built out a facility at the Richland tower site at West Orange, N.J. which for awhile, operated with a DTS (distributed transmission system) transmitter at 4 Times Square to fill in coverage in Queens and Long Island.

Before the new World Trade Center design was finalized, MTVA (Metropolitan Television Association) and the Television All-Industry Committee, consisting of most New York City area broadcasters, considered developing their own broadcast tower site. Numerous locations were evaluated, including Governor’s Island and Liberty Science Center (New Jersey), along with some unique designs for up to a 2,000-foot tower that could fit in a small area. Unfortunately the right combination of finances and politics never came together to allow a separate broadcast tower.

NEW HOME

As the design for One WTC evolved, room was made for broadcast antennas on the spire. Several different antenna designs were proposed to accommodate the needs of broadcasters and their FCC contour limits. The original designs had the antennas inside a radome but this would have made maintenance difficult. Financially, the cost to build out a new facility at One WTC didn’t make sense to many broadcasters as the Empire State Building site was “good enough,” especially since most viewers watched the stations via cable.

The equation changed in 2016 when the FCC announced the spectrum incentive auction which would require many stations to change channels with the commission covering the costs. At the same time, studies were launched to look at designs and costs for improving the antenna system at the Empire State Building. With the limited space at Empire, One WTC started looking more attractive.

At One WTC, John Lyons, assistant vice president and director of operations for New York City real estate company Durst—which jointly owns One WTC with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey—threw out the original designs for multiple antennas on different channels and came up with a simplified antenna system with only two UHF antennas using RFS panels that allow variable polarization—a 40-panel array near the top of the spire, 96-panel array lower on the spire—and some additional antennas for VHF TV.

Lyons was able to convince One WTC management to eliminate the radome. Finally, with the advent of solid-state transmitters, no analog transmitters, and elimination of separate rooms for separate stations, he was able to fit everything on half of the 90th floor. This greatly reduced the overall cost and made One WTC more attractive.

One concern was that signals from One WTC would not penetrate the “midtown mountain” of skyscrapers and coverage to the north would suffer compared to the lower, but more centralized, Empire State Building. As Frank Beacham describes in his column in this month’s issue, MTVA decided a test was needed to see how well One WTC would perform in Manhattan and surrounding boroughs.

TESTING THE SYSTEM

I designed the test configuration and methodology for the test. Unlike conventional FCC field measurements which required multiple readings at 30-foot antenna height on grids or radials, the system I put together used four antennas, two horizontally polarized and two vertically polarized with the same polarity antenna orthogonal to each other on opposite corners of a van roof mount. This system measured the signal about 8 feet off the ground and the different antennas provided some space diversity (Fig. 2). No time was wasted raising and lowering a mast.

Jeff Birch at CBS provided a van for testing as well as an engineer to drive it. Bill Beam from Ion built the test panel shown in Fig. 2 as well as the antenna support structure. I was along for many of the overnight measurements and analyzed them the next day.

This configuration allowed a full set of measurements to be taken at 258 sites on 10 signals from Empire and two (VHF and UHF) from One WTC all in under 10 minutes per site, a total of 3,096 measurements per antenna. My analysis of the results compared minimum, maximum and average signal level and SNR from each of the four antennas as well as the number of antennas where lock was achieved on a Hauppauge Aero-M mobile TV tuner and R&S ETL TV analyzer. Raw data was distributed to the MTVA stations as well as a spreadsheet pivot table summary I created.

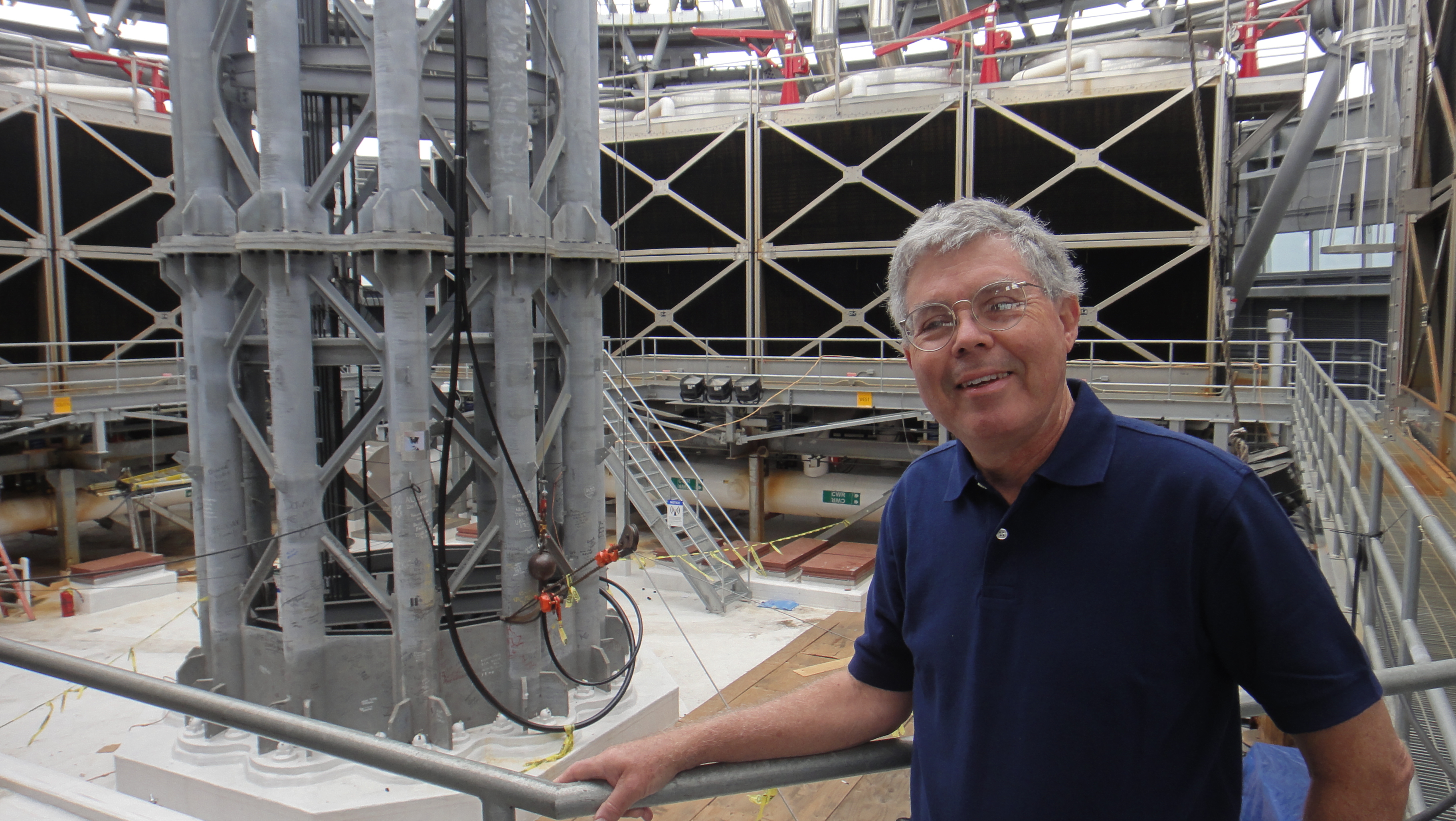

While broadcast facilities at One WTC were being built, the broadcasters lost in the attack on the World Trade Center towers on Sept. 11 were not forgotten. John Lyons remembered them during the events launching the new broadcast facilities and the electricians and workers placing the new antennas left messages on the base of the spire memorializing them. If you look closely in the photo of me (Fig. 3) at the base of the spire prior to starting testing in 2015 you can see some of the inscriptions below the rigging and transmission lines to the test antennas.

WNJU was the first station to begin broadcasting from One WTC on June 23, 2017, using a Rohde & Schwarz 108 kW transmitter, (Google “Telemundo 47 y NBC retornan al World Trade Center” for a video of the event). If you look quickly you might see me on the right of the group in front of the transmitter.

WNJU was joined by six MTVA member stations who had participated in the measurements and eventually five other full-power and low-power TV stations. Other stations have construction permits for the site. The design of the system with two UHF antennas and two combiner systems has proven itself as it allowed stations to switch between the two systems to stay on the air as new stations were added to the combiner and later during the July 2019 repack channel change.

In this article I mentioned a few of the people who played a role in restoring broadcasting in New York after 9/11. There are many more I didn’t mention that were key to the effort. Every TV engineer in New York was active in the recovery, if not in getting the broadcast facilities restored but also in making sure cable companies were able to get TV station programming and news reports from Manhattan out to the rest of the world. Network and station groups provided the people and support that was essential and manufacturers’ engineers and installers were there as well. The recovery effort from 9/11 is a testament to the dedication of the broadcast community, stations and suppliers alike, to provide the public with news and entertainment.

As always, I welcome comments and questions. Email me at dlung@transmitter.com.

The first part of this two part series on 9/11 is available here.

Doug Lung is one of America's foremost authorities on broadcast RF technology. As vice president of Broadcast Technology for NBCUniversal Local, H. Douglas Lung leads NBC and Telemundo-owned stations’ RF and transmission affairs, including microwave, radars, satellite uplinks, and FCC technical filings. Beginning his career in 1976 at KSCI in Los Angeles, Lung has nearly 50 years of experience in broadcast television engineering. Beginning in 1985, he led the engineering department for what was to become the Telemundo network and station group, assisting in the design, construction and installation of the company’s broadcast and cable facilities. Other projects include work on the launch of Hawaii’s first UHF TV station, the rollout and testing of the ATSC mobile-handheld standard, and software development related to the incentive auction TV spectrum repack. A longtime columnist for TV Technology, Doug is also a regular contributor to IEEE Broadcast Technology. He is the recipient of the 2023 NAB Television Engineering Award. He also received a Tech Leadership Award from TV Tech publisher Future plc in 2021 and is a member of the IEEE Broadcast Technology Society and the Society of Broadcast Engineers.