Video Forensics: Where 'Quality Control' Can Mean Literally Life or Death

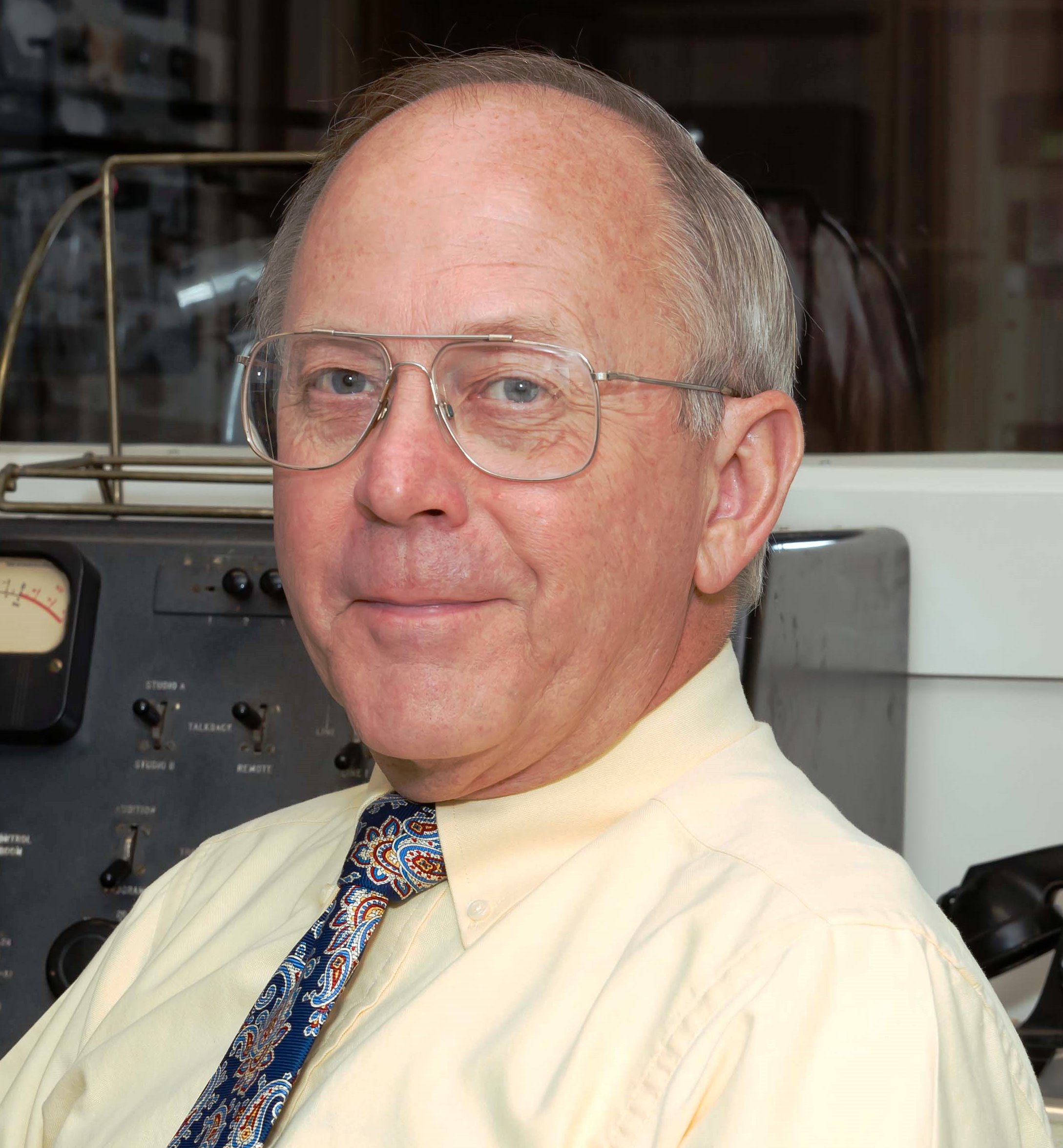

COLUMBIA, MD.—For two decades, Ed Grogan has been hunkered over video monitors and computer terminals performing a very unusual type of video “quality control.” This particular QC work, however, doesn’t result in less-than-perfect footage being sent back to the colorist or returned to the production company to be reshot. In Grogan’s case, what he sees or doesn’t see may make the difference between American lives being lost or unnecessary deployment of big-ticket military resources.

Grogan, a four-decade civilian employee of the U.S. Department of Defense, has spent half of his career directly or indirectly involved in the relatively new field of video forensics—a painstaking and careful analysis of recordings produced by enemies of the state for any evidence of less-than-honest presentation of events, and any and all clues that could spell fakery.

So, why the interest in such video?

Grogan spelled out the answer very bluntly.

“American lives may be at stake,” he said. “Terrorists don’t get paid unless they can show that they killed or injured Americans,” adding that terrorists are not always inspired by idealism or religious fervor, but rather as a means of financial support for themselves and their nefarious activities.

“Sometimes they manipulate the video they’re submitting for payment to show things that didn’t really happen,” Grogan added. “In other cases, recordings are prepared for propaganda purposes—to show that they fought with the ‘infidels,’ to show that they are in tune with the mission, and to try and get others to follow along in what they are doing.”

Grogan offered a recording of a motorized improvised explosive being remotely piloted to explode under a military vehicle as an example of this attempted video legerdemain.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

“In some of the videos it was obvious that the bomb went off early by several frames,” he said. “This probably damaged the radiator rather than the main parts of the vehicle. The bad guys drop a few frames and this moves the explosion so that it looks like they made a direct hit on the vehicle or whatever when they really didn’t. That’s quite creative—just offsetting things a few frames. They haven’t necessarily been good at this sort of manipulation, but have gotten better over time—at least some of them.”

Grogan speculates that the quality improvements may be the result of terrorists now relying on professional videographers and post-production specialists.

“We’re seeing really good skill sets in some of the more recent stuff,” he said. “They do make mistakes from time to time, though. Sometimes they’re not good at greenscreen work, or they do a garbage matte and someone will put his hand right through the matte. Maybe this is just for a frame or two, so you have to look quickly.”

TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE

In the case of the military video forensics, decisions as to whether it’s real or manipulated have to be rendered very quickly to avoid either placing lives at stake or unnecessarily—and very expensively—deploying military resources that could be better utilized elsewhere.

“We have to look at all the videos and make decisions based on this evaluation, because if the videos are real, someone has to be alerted as to where American or allied forces might have been killed or injured,” Grogan said. “I get calls every now and then with someone saying ‘we’ve got some footage and they want a report all the way up to the President—what do you think?’ They’ll tell us ‘you’ve got 20 minutes; please send us your thoughts.’”

MANY CLUES IF YOU KNOW WHERE TO LOOK

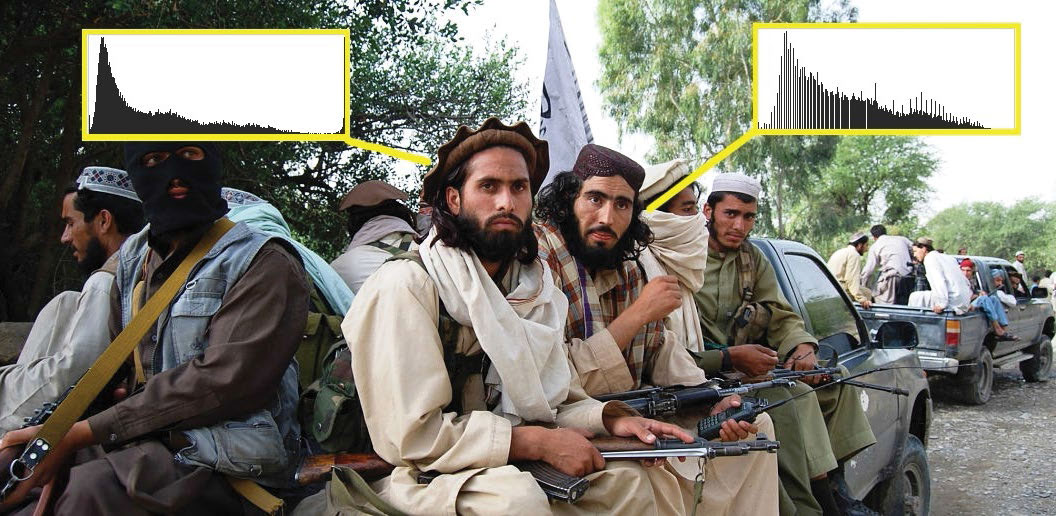

During his career as a video forensics analyst, Grogan has compiled a checklist of some 90 “fingerprints” that could suggest less than truthful presentation of events.

“Any time I saw what appeared to be a mistake, I wrote it down.” Over time he was able to reduce the original list down to about 50 items. These include:

● Stuck pixels

● Errors in focus and lighting in various parts of images

● Gamma errors

● Reflections that don’t match the object supposedly casting the reflections

● Histograms that don’t match across certain scenes

● Errors seen in shadows and reflections of objects

● Inconsistent black levels across a frame

● Incorrect intermixing of even and odd video fields

● Mixing of 8-bit and 10-bit video

TOOLS OF THE [BOGUS VIDEO] TRADE

Grogan said terrorists have been known to use any tools that can be pirated to doctor video; however, some of the bad guys do stay up-to-date with post-production software and may even secure legitimate copies.

“Over time, terrorists have gotten fairly good at creating stuff that was faked to make their point,” said Grogan, adding that there are exceptions. In one case, implementation of Adobe software by a less-than-fully-knowledgeable group resulted in much consternation by forensicists.

“This was back in the analog NTSC and PAL days. We were seeing a lot of stuff that was really, really weird,” he said, referring to motion artifacts being observed. “It was just plain stupid and we couldn’t explain why.”

Eventually the answer came from an individual who had knowledge of video production as practiced in the Middle East.

“Through luck we got to talk to this guy,” he said. “And he told us what was happening, saying, ‘Oh, I can explain that. We opened the box from Adobe, loaded it and ran it. We took the video in and processed it and outputted it. I knew that it was set for American standards and everything we were doing was PAL, but we were directed not to change any settings, so the software converted the (frame rate, and line count) going in and coming out. This was the philosophy. Don’t touch the software settings. If it came from the company that way it must be right!’”

This quickly explained the dropped/added frames and other previously inexplicable artifacts observed in the video.

HOW DO YOU GET TO BE A VIDEO FORENSICIST?

Asked about his career track, Grogan was quick to state that scrutiny of video was not really part of his educational track, as his formal training was in electrical engineering. Shortly after taking his BS degree from Drexel University, he first took a job at the Philadelphia Navy Shipyard while earning his MSEE. Grogan then accepted a position in Washington, D.C., with his initial duties involving military communications and the development of engineering solutions for problems being reported in the field.

“I never worked in broadcasting,” said Grogan, “But I was the AV guy in high school, and while I was in college, I did do some work in video production for a cable TV company, but I liked the hardware side of things better.”

His eventual springboard into video detective work stemmed from a conversation with a co-worker.

“We had a secure phone and one of the guys said that he couldn’t wait until we had a picture phone, as then he wouldn’t have to take the steps necessary to verify who was calling. I said ‘yeah, provided you could trust the video, because I could fake it.’ This was around 1996 and I knew enough about Hollywood then to know things like this could be faked.

“I wrote a technical paper on this and rather quickly the question arose that if I could create fake video, could I detect it? My paper got circulated through the DoD and I was asked to do some briefings. Later, I was asked to teach classes on the effects of video deception. This is how I entered the world of video forensics.”

Grogan continued to screen recordings for tampering, eventually doing “post-graduate” work of a sorts with a DoD-sponsored four-month stay in Hollywood, where he had free access to most all of the post-production houses there and got to observe that community’s professionals at work in creating visual effects for the big screen.

“That was extremely helpful,” he said.

THE NEXT GENERATION

Although not now directly involved in video forensics, Grogan does step in to assist from time to time, and observed that sometimes identifying video prestidigitation can depend on one’s perspective. He recalled a particular incident in which he was asked to evaluate a scene involving movement of a vehicle at dusk.

“I said that I didn’t think it was possible for the camera to capture such a lousy image of the truck while at the same time producing such gorgeous images of the stars above,” he said. “Sometime later, one of the new hires—a young kid really—looked at the same video and recognized the buildings in the scene, saying ‘Oh that’s from the so-and-so video game.’ He correctly identified footage the bad guys had appropriated from a game.”

Grogan recalled another case involving propaganda footage of an airliner being shot down. He calculated the required elevation of the camera to capture the images shown, and quickly determined that it couldn’t have been on the ground.

To further “ice the cake,” Grogan said one of the younger teammates was able to identify the explosion in the propaganda video as having been excerpted from a video game. “We were able to match it pixel-by-pixel,” he said, noting that “perhaps there just may be a future for people who are hung up on playing video games.”

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.