Protecting the future

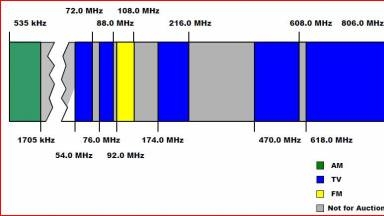

In terms of RF spectrum, the broadcast industry has been relatively stable. Other than digital modulation, the AM, FM and TV spectrum didn’t change much until 1952, when the FCC added 420MHz of UHF spectrum, known as channels 14 thru 83. Until then, the band was reserved for military use, primarily radar.

In 1983, the FCC removed an 84MHz block of virtually unused UHF channels from 70 thru 83 from the TV broadcast band. These channels were reserved for TV translators, and only about 20 translators in this block were ever licensed.

About 25 years later, 95MHz of the 700MHz spectrum containing UHF channels 52 thru 69 was divided into five blocks, auctioned in what is known as Auction 73 in 2008 and abandoned by broadcasters in 2009. It concluded by issuing 1091 licenses and raising a total of $19 billion in winning bids. This is the result of spectrum released by the transition to DTV, also known as the digital dividend. We don’t specifically know where that $19x1010 digital dividend went, and within the context of broadcast engineering, that issue is not relevant. What is relevant is how the spectrum dividend is administrated and its potential effects on DTV transmission and reception in the future.

Oh, they would never do that

Until recently, the FCC guarded the domestic RF spectrum like the U.S. Army guards the gold reserve at Ft. Knox. Unfortunately, the FCC has transformed the RF spectrum from national treasure to a profitable commodity and political piñata, still to be treasured because of its power and worth.

In terms of RF spectrum, the broadcast industry has been relatively stable. Other than digital modulation, the AM, FM and TV spectrum didn’t change much until 1952, when the FCC added 420MHz of UHF spectrum, known as channels 14 thru 83. Until then, the band was reserved for military use, primarily radar.

In 1983, the FCC removed an 84MHz block of virtually unused UHF channels from 70 thru 83 from the TV broadcast band. These channels were reserved for TV translators, and only about 20 translators in this block were ever licensed.

About 25 years later, 95MHz of the 700MHz spectrum containing UHF channels 52 thru 69 was divided into five blocks, auctioned in what is known as Auction 73 in 2008 and abandoned by broadcasters in 2009. It concluded by issuing 1091 licenses and raising a total of $19 billion in winning bids. This is the result of spectrum released by the transition to DTV, also known as the digital dividend. We don’t specifically know where that $19x1010 digital dividend went, and within the context of broadcast engineering, that issue is not relevant. What is relevant is how the spectrum dividend is administrated and its potential effects on DTV transmission and reception in the future.

Who’s on first

Recently, a couple of new events illustrate the FCC’s new focus. When the FCC issued a call for white space database managers in late 2009, nine organizations, including Google, responded and were all conditionally designated in January. In April, well after the deadline, Microsoft pushed the FCC to be designated, which happened in late July. Now, Microsoft and the other nine designees are in an FCC trial period lasting “at least 45 days.” For more info on white space management, see http://www.fcc.gov/encyclopedia/white-space-database-administration.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Instead of relying on the FCC to protect guard bands and broadcast-licensed channels, broadcasters will have to rely on Microsoft, Google or some other corporate entity to police the broadcast television bands. How healthy is that?

One of the things I always liked about my broadcast engineering career was that the FCC easily earned my respect almost every day. Back then, the FCC was primarily concerned with a couple thousand broadcasters, police (public safety) radio, radar, hams and one phone company, Ma Bell.

The FCC required broadcast operators and engineers to pass written tests. It required stations to maintain their equipment and document their operating perimeters. It monitored the RF spectrum extensively and enforced rules fairly and strictly. I’ve met some outstanding FCC people who were as dedicated to the preservation and protection of RF spectrum as any broadcaster (or ham for that matter), and they did a darn good job at it. Then along came cellular communications, the Internet, Wi-Fi, DTV and who knows what, overwhelming the FCC’s vision and diluting its broadcasting and broadcast engineering regulation staff.

Digital soap

Anytime you throw around billions of dollars, you’ll get attention, but the focus of that attention may not be exactly what you had hoped. Let’s say you burned through $15 billion to build a network to bring high-speed Internet to rural areas, only to discover later that its base technology could affect terrestrial GPS service up to a mile above the terrain. Suddenly, investors and the government are asking questions.

Interference from this new network could prevent an estimated 500 million GPS-enabled devices and services, such as airplane tracking, clock synchronization, emergency communications and other critical missions, from working properly. Yes, the company is LightSquared, and yes, it is indicative of a new attitude that reminds broadcasters that the bullet-proof glass is gone.

At a congressional hearing last month, a government official in charge of maintaining the GPS system expressed concern about the impact of your planned network. Since then, at least two high-ranking officials, one an Air Force general, told Congress in classified briefings that they felt pressured by other government leaders to change their testimony about the same project to make it more favorable to the company. Of course, LightSquared is saying it is not its fault.

In an open letter, available at http://www.lightsquared.com/press-room/press-releases/open-letter-from-lightsquared-ceo-sanjiv-ahuja/, 4G LTE provider LightSquared defended themselves. Addressed to “Americans Everywhere,” company CEO Sanjiv Ahuja discusses issues facing the wireless spectrum start-up, including complaints that the company’s use of bandwidth interferes with GPS signals. This story, as they say is still developing.

Good fences make good neighbors

Forget politics and let’s talk digital. The LightSquared scenerio is all about 4G. This fourth generation of wireless cellular standards sets peak speeds at100Mb/s for high mobility users such as those in vehicles, and 1Gb/s for low mobility communication. It improves security for IP-based mobile broadband and deals with technologies like WiMAX and Long Term Evolution (LTE).

According to the website http://www.goinglte.com/what-is-lte/, LTE is the final step toward the 4th generation (4G) integration of radio technologies, successor to the current Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) 3G technology, which is based upon WCDMA, HSDPA, HSUPA and HSPA technologies. LTE is not a replacement for 3G, but an update technology that will enable it to provide remarkably faster data rates for both uploading and downloading.

LightSquared uses a unique hybrid of satellites, cellular and wireless to achieve its 4G LTE goal. According to some involved parties, one central problem was that the power output of some of the systems was higher than customary in the bands they were transmitting in, which overloads some GPS front-ends and can splatter into adjacent GPS bands.

Not every 4G system affects GPS, but apparently LightSquared’s does. Or it did. Or it won’t. The jury is still out on that detail, and the story is still developing in the national news. It’s a revealing story broadcasters are following closely because it provides more clues to the regulatory terrain ahead that terrestrial broadcasters will have to navigate successfully.