The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Digital video effects were first introduced to the broadcast marketplace in the early 1970s. The first commercial unit was the Vital Industries Squeezoom. It had up to four channels of video and could perform the type of scaling functions that we see on our computer screens every day. Squeezoom was the first digital video-effects unit available. It was followed by the NEC Mark I and Mark II DVEs, which Thomson Grass Valley marketed with its line of production switchers. Joining these were Abekas, Ampex, Quantel, Sony and others, all of which built hardware-processing devices to produce digital effects.

Manufacturers are building multiple channel DVEs into current production switchers. Shown here is the Kalypso production switcher from Thomson Grass Valley.

Processing progress

Article continues belowAt the same time, some companies were putting research efforts into generic image-processing engines. Abekas, Thomson Grass Valley and others pursued this market and eventually built digital video switchers that used image-effects processing. But the device everyone sought was a general-purpose computing platform that could manipulate image data in real time. There were predictions that the days of the special-purpose box, i.e. video switchers and DVEs, were numbered, and that HP, SGI, Sun and others would own the broadcast space in a matter of years.

Until recently, general-purpose computers weren't powerful enough to make complex image transformations in real time. Even today, much of the complex processing is offloaded to processing engines tuned specifically for that purpose. We can expect that software will be able to run at sufficient speed to accomplish most, if not all, effects processing for standard-definition pictures in the coming years. HDTV processing probably will lag some years behind, because the amount of data that must be processed to generate complex effects in HD is simply too large.

Processing update

The more we expect, the more we seem to drive the creative engineering community to develop more complex and capable solutions. Computing platforms have taken the lead position for some applications, especially those where the work can be done offline outside of live production. In those instances, rendering time is not an issue, and pre- or post-production techniques are most appropriate.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Live mattes and DVEs

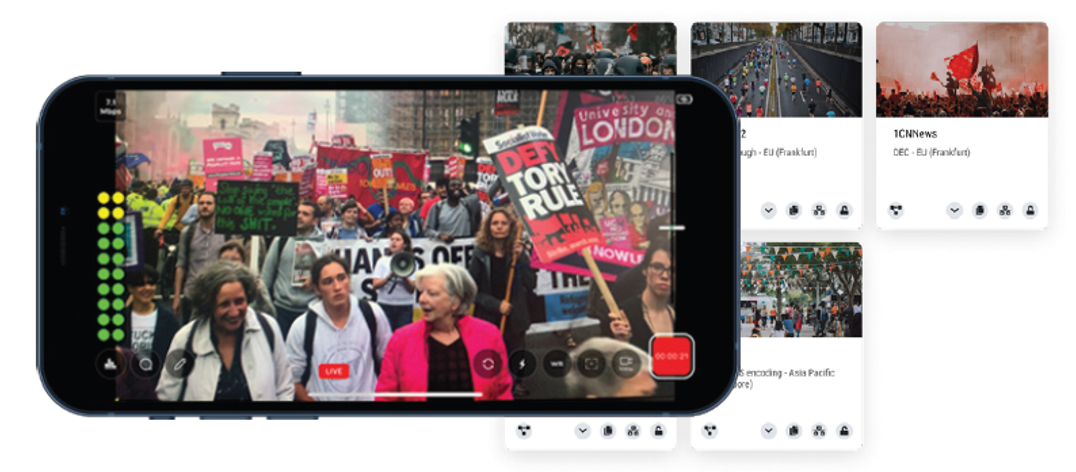

Sophisticated mattes and DVE moves must be created online for live sports and news, and for high-profile productions of major entertainment events (Emmys, Oscars, etc.). This requirement has grown in sophistication, and has encouraged the manufacturers of digital production switchers to include increasingly complex effects capability in tightly integrated, or internal, DVE channels. Pinnacle, Ross, Sony, Thomson Grass Valley and others all have built multiple-channel DVEs into current production switchers. Some have a limited range of capability. But, increasingly, the capabilities that were once the province of ADO and its successors have shown up inside production switchers. And there is every reason to expect this trend to continue.

Live graphics

Graphics, in many respects, are a different matter. Pre-canned graphics elements that appear to be created live can be played live in productions. Consider the head shots used in sports. They are obviously pre-produced, but their live insertion is a critical production element. These capabilities are well supported by special-purpose computing platforms, often with graphics engines under software I/O and user-interface control. Triggering them from production switchers is commonplace. For sports, it is common to have the official time and score delivered to the graphics engine in real time, allowing complex presentations to be made on-the-fly using templates created in advance.

For decades, this technique has been used for election-night graphics; now it has moved into the mainstream. Graphics-intensive computers have adapted quite well to these special-purpose needs. An example is the use of “first and ten” graphics inserted live at sports venues. The computation is complex. Data from the camera(s) on pan, tilt and zoom is fed to a computer that calculates a 3-D representation in real time and provides key signals to either an internal or external keyer. These capabilities are closely related to virtual sets and are extensible to a wide range of future uses.

John Luff is senior vice president of business development for AZCAR.

Send questions and comments to:john_luff@primediabusiness.com