The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Always include extra inputs. Eventually new consoles will be old and dead inputs will happen.

Just wait till the news anchor hears his own voice four frames out of sync — best to consider building mix-minus outputs.

When television first erupted from the radio only landscape audio mixing consoles used rotary attenuators to adjust the level of the audio. Filtering and other modifications were most often done with outboard devices. Stereo was barely a thought — recording was on ¼-inch (or larger) audio tape recorders at 15 inches per second or more.

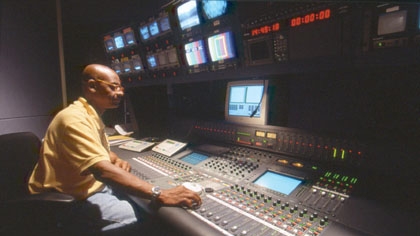

Ah, progress! Today a console in a news production studio may have three to six times the number of faders, built-in EQ, high and low pass filters, dynamics (compression and limiting), multiple stereo busses, perhaps surround sound, mix-minus outputs for IFB, complex monitoring matrices, analog and digital I/O, digital memory, perhaps even digital mixing. Complex systems of auxiliary devices can provide effects — reverb, specialized dynamics processing, patching, audio routing switchers, analog and digital converters, and plenty of other peripheral devices are often part of the mixing environment. If you don't have a well-trained audio expert on staff the task of planning a new mixing room, or just revamping a worn-out control room, can be quite daunting. Even with an expert along many video engineers feel considerable trepidation when considering audio consoles that can easily cost over $100,000 and much more for the highest-quality digital consoles.

As in all things, consider the intended use first. Many times the project is a renovation of an existing system. This often includes goals such as improving reliability for the old console for which parts are no longer available. If the need is to build a new facility that will last 15 years until a replacement can be justified (which is not unusual in this business) then perhaps digital options should be thoroughly and thoughtfully evaluated. The march of mixing consoles into the digital era has been quite rapid, and modest digital consoles can be purchased for well under $10,000. Let's look first at applications in television and how they might set the direction for a console evaluation plan.

At the top of the list is to set the physical scale of the product you are seeking. Is this no more than a minor audio production room, or does the console need to be capable of both news and entertainment uses? A studio that does only heavily formatted news might need fewer than 24 inputs on the audio console, with perhaps six to eight microphones, capacity for feeding pre-recorded clips (stories and bumpers), signature music, ENG feeds and maybe a handful of routing switcher outputs for sources that are less frequently needed. How many inputs are used simultaneously for the typical productions will set a minimum size, but always include extra inputs. Eventually this new console will be old and dead inputs will happen. Leaving room for growth now will protect you against future failures. Ask the manufacturer if the inputs use a common circuit board for a group of faders (often about four to six inputs), and add two modules beyond what you think is the minimum needed. One module gets you some growth, the other maintains some redundancy with that growth.

Consider features that are unusual to broadcast (radio and television), like mix-minus outputs. Any console can mix mikes and recorded clips. Today, outside of radio on-air consoles, virtually all consoles have EQ features. But mix minus is heavily used in many broadcast applications where talent needs to receive the mix for monitoring. By the time the video system is done processing the picture you often need to delay the audio to match. Just wait till the news anchor hears his own voice four frames out of sync — best to consider building mix-minus outputs. Some television consoles can provide a mix-minus output for every fader position. Most also allow for delay adjustments on each fader, permitting more flexibility when matching the delays in a complex video system.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Think carefully before rejecting a digital console. Digital consoles in modest sizes do not have to cost more than analog consoles these days, nor are they inherently more complex to install. Manufacturers in North America, the Pacific Rim and Europe have all designed consoles with both analog and AES inputs. They also can provide the analog monitoring and program outputs needed for many installations. If the console is to be useful as production technology continues to become more and more digital it is wise to carefully look at the costs for a digital solution now. That may well prevent another rebuild in just a few years when the rest of the system is fundamentally digital.

The key to this important development in audio mixing is the rapid progress in DSP technology and specialized silicon implementations for both professional and consumer audio equipment. Take a look at the audio card in a modern computer. Not many parts there, but it allows mixing in the digital environment for a number of real and virtual inputs, for less than the cost of one rotary fader. It is likely that the progression of digital mixing will continue, with more capabilities and lower cost. However as the complexity rises the cost of developing software goes up dramatically, and it is not likely that high-end consoles to reduce in price as rapidly as modest consoles. One could expect that digital consoles will be less expensive in modest sizes, partly because the fabrication and checkout of each console is considerably less expensive for the manufacturer.

It also is valuable to look at the growth in the industry and how it might affect the expectations for consoles in the future. One of the key dynamics in the broadcast industry is the repurposing of media. Many local TV stations are running a Webcast live or perhaps even a 24-hour news channel. A console that has the ability to mix for several simultaneous uses of the basic program may well be an important consideration. While simple stereo consoles suffice for today's environment, perhaps two or three stereo outputs may be required (without giving up precious sub mix groups). Don't forget the slow but important deployment of surround sound either. While you don't have to have a surround sound console to create the effects and surround channels, panning in the surround is difficult without the proper features.

Finally, look long and hard at consoles with full memory. If the audio console is going to be used for more than one program it is highly useful to be able to set up the inputs, EQ, routing and panning, monitoring, and outputs and then store it to memory for the next production. This also allows multiple operators to have a setup that matches their own style better. Needless to say it also allows rapid reconfiguration if, perhaps, one console is used to mix two back-to-back programs from two studios, as is often the case. As in all things this capability comes with drawbacks. Complex consoles with memory often don't wake up quickly from a power off reset. Consider using a UPS to keep the console from becoming a liability when the unexpected lightning storm causes the lights to flash!

John Luff is vice president of business development for AZCAR.