The Changing Face of the Television Industry

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Who knows what is going to happen next in the television industry? Certainly I don't. For several decades now, I have been watching the business in which I have spent most of my career undergoing one wrenching change after another.

The recently announced sale of control of NBC (known these days as NBC Universal) to Comcast (traditionally known as a cable MSO) is the latest and rather one of the most stunning changes I have ever witnessed in television. As a headline on the front page of the Business Section of the Dec. 7, 2009 issue of The New York Times succinctly put it, "NBC-Comcast Deal Puts Broadcast TV in Doubt."

LOOKING BACK

When I joined NBC in 1979, it was owned by the company that founded it in 1926, RCA (also known as the Radio Corp. of America). It was one of three national television networks, and, although it was in third place among the three at that time, it still had a license to print money in the back room.

RCA and NBC were both very traditional New York companies at the time. I well remember a graveyard-shift videotape supervisor who always wore a tie and sport coat to work all night. In addition to the television network and the then-permitted five local TV broadcast stations, NBC had a radio division comprised of a network and the maximum-permitted number of owned stations.

I must say that I owe a very large debt of gratitude to NBC for contributing so greatly to my development as a television engineer and technologist. No company I have ever worked for has given me more opportunity to stretch my wings and my mind. It was a great sandbox to play in.

NBC had built up a technology staff that was second to none, and this was combined with the strong will to be the technological leaders of the industry, and backed up with the research and development strength of RCA Labs. This milieu provided the requisite support and encouragement to take intelligent risks and to excel.

Just one example of many, for which I can take no credit at all, was the switch from telco to satellite signal distribution. NBC was not only the first broadcast network to switch to satellite distribution; they were also the first to use Ku-band satellite technology in this way. This bold move raised a major hue and cry of "it will never work" from the rest of the industry. But work it did, and very well indeed, thank you.

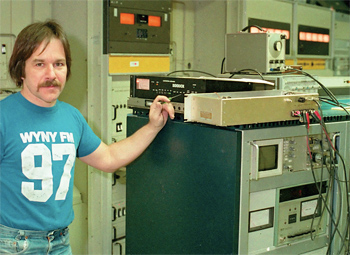

The author checks out the WNBC transmitter on the 104th floor of the World Trade Center in the early 1980s. I remember the many acronyms shared about NBC: Nothing But Confusion, Nobody Cares, and my favorite, Nepotism Before Competence. These were some of those inside jokes that spring up in a company; we shared them internally and laughed, but we did not want to hear outsiders using them. And in spite of the jokes, most of the people one encountered at NBC then really did want to be helpful and supportive.

Under the leadership of Grant Tinker, NBC became well known for putting good shows on the air and developing them into hits: it was not many years before NBC went from "worst to first." Then, the first NBC world-shaking event took place.

I remember the moment I heard that this was happening, at a Christmas party in December 1985. RCA was acquired by GE, who proceeded, as had been predicted, to remove the name of RCA from the face of the earth, except as a plastic label on some TV sets. Still, NBC continued to prosper and progress for some time in spite of the changes.

Somewhere along the way, though, the industry changed and NBC changed. Suddenly, recently, with the pressure of all the cable networks that had begun to produce their own programming and eat significantly into the broadcasters' audiences, television broadcasters began to decide that their broadcast signals were next to worthless, except to extract retransmission consent fees. This in spite of the fact that no cable network can come close to the audience that a broadcast network can command, even when the cable network runs its most popular programming.

NBC, perennially at the bottom of the broadcast network ratings in recent years, is once again leading the way in one respect, in that they decided to cede the precious 10 p.m. time slot to Jay Leno talk, five nights a week. This time slot held so many smart, adult, popular drama programs over the years, including programs such as "Hill Street Blues," "LA Law" and "ER." The only plausible explanation for this is a desire to fill the schedule with cheap programming.

On the technology side also, NBC lost its way. Once the home of the best television technologists in the business—and the technology management staff most willing to take risks and live on the cutting edge—NBC backed away from technology.

Lest we forget, NBC was once the leader of a consortium that was a proponent of a digital television broadcasting system, a system that contributed to the Grand Alliance some of the best technology that is incorporated in the ATSC DTV broadcasting system.

When push came to shove, NBC was the last of the big three networks to adopt HDTV, resisting as long as possible, and doing no innovating at all. After once supporting a thriving Technology Lab, NBC shut that effort down in the early 1990s, resurrected it in a reduced form later, and subsequently shut it down again.

Recently, a friend, the founder of a company that manufactures television equipment, said something to the effect that "these days nobody at NBC knows how anything works."

The next chapter of NBC's history will apparently be written under the control of Comcast. Some tell us this could be good for NBC. It could also, in this writer's opinion, be the same type of kiss that GE gave RCA in 1986. This could be a Requiem for a Broadcasting Heavyweight. Only time will tell.

FOLLOW-UP

I have two follow-up items regarding the topic of the two previous columns: loudness. First, I have become aware that a committee of the ITU has generated a draft Recommendation on "Operational practices for loudness in the international exchange of digital television programmes."

This is, at present, a two-page document; much shorter than the ATSC RP on loudness. It contains the same basic recommendations, however: make loudness measurements using the algorithm defined in ITU-R BS.1770; and use the target loudness value of -24 LKFS.

Secondly, in one of my loudness columns I made reference to the "subwoofer signal."

I have been reminded that the precisely correct term for this signal is "low frequency effects (LFE)". Although I knew this, I have tended to use "subwoofer signal" because I think more people understand this term than are familiar with the term "LFE.". Perhaps someday someone can explain to me just what is wrong with the term "subwoofer signal." After all, we call the signal that ultimately feeds the left-channel speaker "left," regardless of where in the production, post production, or broadcast chain it is found, so why don't we just call the signal that ultimately feeds the subwoofer channel speaker "subwoofer?"

Randy Hoffner, a veteran of the big three TV networks, is a senior consulting engineer with AZCAR. He can be reached through TV Technology.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.