Synchronizing Audio and Video

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tracing the source of lip sync errors can involve a systematic approach through the signal chain of each subsystem of a broadcast facility, making sure that the error is zero at each stage.

But how exactly do you determine when you are in sync? While there are various test and correction devices available, most often we rely on our eyes and ears. The problem is that not everyone perceives lip sync errors in the same way.

How accurately a person can sync up audio and video depends on many factors, including distance from viewer to screen; screen size; whether the image is a long shot or a close-up; whether the image is in SD or HD; and microphone techniques.

This issue is addressed in the BBC white paper, "Factors affecting perception of audio-video synchronisation in television," by Andrew Mason and Richard Salmon, which is part of "AES-R11-2009: AES standards project report - Methods for the measurement of audio video synchronization error."

In listening to and looking at the natural world, light from a scene arrives at our eyes instantaneously, while sound takes time. A sound farther away from us takes longer to reach our ears than a sound closer.

We could easily expect this in a television scene. Some audio delay may seem natural in a mid- or long shot, while totally off in a close-up. Further compounding the issue, the distance from a microphone to a sound source also factors into the overall delay.

PERSONAL PERCEPTION

So it shouldn't come as a surprise that in a BBC study that Mason and Salmon cited, where test subjects who dialed in a delay that they believed would correct deliberately induced A/V lip sync errors, there were wide variations in responses.

The authors noted the test subjects found that correcting lip sync errors was a difficult process. Even though sound arriving before video is generally easier to detect because that doesn't occur in nature, some of the test subjects had trouble discerning which came first, the audio or video. Others could tell that the sync was off, but when they tried to correct it, they had difficulty finding that in-sync spot. And there were those who weren't very sensitive to sync errors at all.

An interesting finding was that variations in response were slightly less for HD than SD, indicating that it was easier to detect lip sync errors with HD video. Fortunately, it was also easier to correct errors with HD.

Could there be a similar variation in response with station operators or quality control technicians? Are there training tools and methods that could help us be more discerning to lip sync errors? These would be interesting areas for further study.

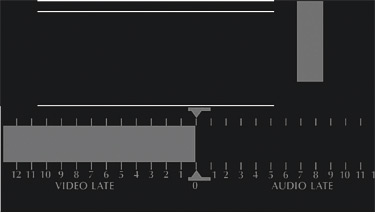

Fig. 1: BBC test signal for synchronizing A/V While a broadcaster has control of lip sync issues within a facility, once it reaches the consumer, all bets are off.

"One particular area that has grown to be a problem in recent years is the separation in the home of the audio from the video reproduction equipment," said Andrew Mason of the BBC, and chair of Project AES-X177 and also chairman of the EBU Expert Community on Audio. "The development of installations where a big, flat screen presents the pictures; a surround-sound system presents the sound; and the signals for these two come from a separate set-top box; has led to a loss of control of A/V sync in the home. The diversity in the digital TV receiver market has clearly shown that some systems are better than others at controlling A/V sync even within a single device, let alone when they are separate."

SETTING DELAYS

To help viewers achieve correct A/V sync, the BBC has been transmitting a test signal during promotional material on their flagship HD channel, and instructing viewers how to use it to set delays on their equipment. The test signal and method were designed to measure sync errors by eye.

Described in the BBC white paper "Managing a Real World Dolby E Broadcast Workflow," by Rowan de Pomerai, also a part of AES-R11-2009, the test signal consists of an audio snap as well as video graphical elements synchronized to the snap (see Fig. 1).

One of the graphical elements is a horizontally expanding bar, which moves across a time scale marked in video frames. A viewer can note at what tick mark the bar reaches when the audio snap is heard, and then adjust the appropriate delay settings on the home equipment until the bar reaches the center of the scale (the zero tick) indicating correct sync.

As de Pomerai noted, the BBC meticulously went through their entire play-out, distribution, and transmission signal chains to ensure the test signal was correctly timed when received off air. This was quite an undertaking, but has paid off in reduced complaints from viewers.

Mary C. Gruszka is a systems design engineer, consultant and writer based in the New York metro area. She can be reached via TV Technology.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.