Revolution Becomes Evolution

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some of us veteran production people can dimly recall a time when creative control of a video project rested not in the hands of the writer, producer or director, but in the hands of a beneficent tyrant—the video engineer. The engineer, after all, determined whether the electrical characteristics of a particular television image were "legal," or technically permissible under the stringent specs of broadcasting. These criteria excluded overly colorful content, houndstooth-patterned blazers and open flames. Darkness was a no-no; forget chiaroscuro. Shiny objects didn't exist. And, of course, anything white. The engineer's veto was final and absolute.

Problematic content of all kinds was severely restricted for dozens of very valid technical reasons—until the advent of solid-state imagers and automatic camera circuitry. Technologists of the 1980s would never have called their 30-year-old industry "immature," but the technological revolution, which has arrived since then, has unbound creativity from pragmatism and freed the imagination.

OPTICAL TO VIRTUAL

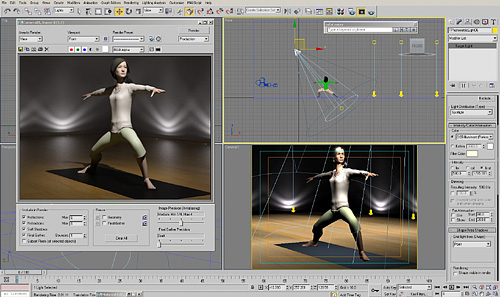

Autodesk 3D Studio MAX There's a parallel story here, but it requires a leap—horizontally—away from a world grounded in real, optical imagery of living beings and finite objects. By the late 1980s, the first practical computer animation systems were emerging, but the obstacles to their broader use were formidable. They invariably required high-powered workstations from Sun, Symbolics and Silicon Graphics, with price tags that began at six figures. The software which created and rendered 3D models was nearly as expensive. And, most significantly, not a single animated frame could be produced without an entire roster of genius-grade staffers, who variously tended the hardware and software and coaxed fanciful output from the recalcitrant systems. Like their video engineer counterparts, they never sought to stifle creativity, but rather to work within the limited technological palette they'd been issued; and yet the effect was the same—a long list of restrictions and "can't do's," with no avenues for appeal.

In a revolution very similar to that which dethroned the video engineer (or at least restored him to his rightful place), a succession of hardware and software innovations has unyoked computer generated imagery, or CGI, from its burdensome technological legacy, and provided the tools for the comparatively effortless creation of CGI elements and 3D animation. Over the course of a decade, nearly-automatic procedural animation, ultra-realistic rendering engines and streamlined user interfaces have democratized CGI and 3D, much as the arrival of the inexpensive high-definition camcorder has empowered would-be directors and cinematographers.

TROUBLESOME TREND

But is the virtual world of 3D and CGI on the verge of crumbling? Some have expressed concern over the October sale of 3D software developer Softimage to Autodesk, which now holds some of the biggest cards in the animation game. Autodesk, as most folks know, developed the "killer app" of computer assisted draw-ing (CAD), AutoCAD, and extending its drawing abilities from two dimensions into three was a fairly logical move for the company. But Autodesk's decision to develop a down-market, entertainment-oriented 3D product, 3D Studio, came at a time when young imaginations had latched on to CGI, and thousands of budding animators cut their teeth on the app and its successor, 3D Studio MAX.

As the market for 3D animation and CGI matured and condensed, developers who had relied on big-ticket software sales gradually saw their fortunes change. In a list of "begats," which would rival the Book of Genesis, the Canadian developer Alias joined with Santa Barbara, Calif.-based Wavefront Technologies, was bought by SGI, and ultimately sold to… you guessed it… Autodesk. Similarly, Discreet Logic, whose powerful Flame/Flint/Inferno compositors created an entire post-production subspecialty, was acquired by the San Rafael, Calif. juggernaut. And Montreal-based Softimage became part of Microsoft before being sold to Avid, where it remained as a related-but-unrelated product offering until its recent sale.

Some think that Autodesk has its sights set on empire building, picking off the jewels of the CGI world one by one. I'm not sure that's the case. I've met and chatted with Autodesk CEO Carl Bass on a few occasions, and that's not his style. I believe that the firm is doing what good companies do… identifying and acquiring the technologies which enhance and extend its focus. As a result of this strategy, Autodesk now boasts a premier character and gaming animation platform (Softimage); the powerful Maya package, a film industry favorite and Detroit's chosen industrial design modeler; and the high-powered Discreet compositing platforms which marry the virtual and the optical.

At the very least, these technologies have found refuge under the Autodesk umbrella—protection from the shifting market forces which have, to greater or lesser degrees, already threatened their survival. But there's a greater potential, one realized by nurturing and growing these unique and specialized brands and cross-pollinating features and tools among the company's products and platforms.

Much in the same way as camera and recording technologies before them, 3D animation and CGI have gradually entered a new phase, one seen over and over at the junction of technology and creativity—the shift from revolution to evolution.

Walter Schoenknecht is a partner at Midnight Media Group Inc., a New York-area digital production facility. You can reach him via e-mail at walter@mmgi.tv.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.