‘Inventing American Broadcasting’—A Look at How It All Began

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Randy Hoffner

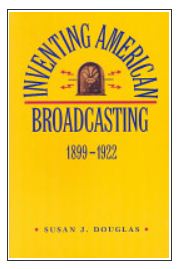

Interested in reading about some old technology? I recently read a book that should interest anyone who works in broadcasting in the United States. The book, “Inventing American Broadcasting 1899–1922,” is by Susan J. Douglas, a professor in the Department of Communications at the University of Michigan. It is part of the series “Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology,” so it has a pretty good pedigree.

When I came across mention of this book several months ago, I was surprised that I had not heard of it before, particularly in that it was first published in 1987. Oh well, I guess I was busy in 1987—in fact I know I was.

This book is a great source for the reader who wants an accurate, unbiased account of just where American broadcasting came from, as well as being “A superb portrait of the communications revolution that profoundly altered 20th-century life,” in the words of Kenneth Bilby, writing in Washington Post Book World.

THE DAWN OF WIRELESS

It is generally agreed that the first commercial broadcasting station in the United States was KDKA, Pittsburgh, which went on the air in 1920. But what led up to that launch?

The young Italian-Irish inventor Guglielmo Marconi arrived in New York in 1899, after having used his wireless telegraphy device in 1898 to assist a Dublin newspaper’s coverage of a regatta. James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the New York Herald, knew of this and offered Marconi $5,000 to cover the America’s Cup yacht races for the Herald. Marconi accepted, and, primitive as it was, this could be thought of as the dawn of wireless, electronic communications media.

While Marconi’s invention was a spark-gap transmitter (which essentially emitted bursts of static) and an appropriate receiving device, and could, therefore, only be used for telegraphy, others had different ideas.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

A young engineer and academic, Reginald Fessenden, thought that the sparkgap transmitter should be replaced with a device that emitted a continuous, sustained wave train, while the receiver should be a device that continuously received this wave train, facilitating the carriage of speech and music.

Two early adopters of wireless were the U.S. Navy and such companies as United Fruit Co., which depended on fast communications with ships at sea. The third group of early adopters was amateur radio operators. Their numbers multiplied until, by 1910, amateur radio operators outnumbered both the U.S. Navy and wireless commercial ship communications. The widespread adoption by amateurs was facilitated by the discovery of crystal radiofrequency detection for receivers. Interestingly, it was the building of a crystal receiver that fueled this author’s interest in the field, although it was much later than 1910.

The first radio broadcast in American history was done by Fessenden on Christmas Eve of 1906. It included speaking, singing, and violin-playing by Fessenden himself, and phonograph music; and it was principally aimed at ships equipped with his apparatus.

As the amateur communications hobby flourished, at some point Westinghouse, an early manufacturer of radio hardware, decided they could sell more receiving sets if they were to broadcast programming for them. At 8 p.m. on Nov. 2, 1920, the newly licensed Westinghouse station, KDKA, Pittsburgh, broadcasting at 360 meters (approximately 833 kHz; KDKA now broadcasts on 1,020 kHz), went on the air and broadcast the election results, setting off a “broadcasting boom” over the next one-and-a-half years.

These, then, are the ultimate roots of the business we work in. Douglas’ book is a very complete and interesting historical account of how American broadcasting emerged from Marconi’s wireless, and the discoveries and achievements that preceded it. It is also a very good accounting of the technologies that were used and developed during that period.

If you work in radio or television technology, you really owe it to yourself to read this book, to learn where your industry came from.

Randy Hoffner is a veteran of the big three TV networks. He can be reached through TV Technology.