A Store-and-Forget Cloud Archive

Al Kovalick

Imagine a program/ data archive so durable, you never need worry about the mechanics of archive integrity for 10, 25, or even 50 years. Impossible? Read on.

The heart and soul of a media enterprise is content—sports, news, movies, dramas, events and much more. Every owner of programming needs to archive the crown jewels. For years these types have been archived on film or video tape. Analog film has excellent archive properties, especially in terms of longevity and resolution. Video tape is problematic due to rapid format changes and playback machine availability.

Today, with file-based being the norm for so many programs, content is often archived on Linear Tape Open datatape and other related formats. LTO is a workhorse and deserves credit for performance and being a de facto industry standard. Several vendors recently announced the latest LTO6 drives (2.5 TB native, 160 MBps) that will be available in the next few months.

But all tape/drive formats suffer with obsolescence. For example, no LTO5 drive can read LTO2 tape. Moving up a generation creates orphans, often with valuable content in store. Sure, files can be migrated to the next-generation store, but with cost and complexity.

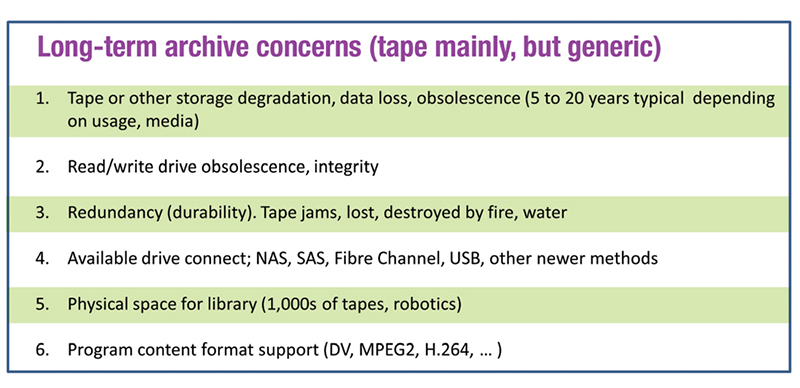

Not to over-simplify the topic, but all six items listed in Fig. 1 are a constant menace to the media enterprise. True, number six is not related to storage technology, but is nonetheless a thorn in the side of all media professionals. The good news is there is a new product category that potentially eliminates most of the concern for items 1–5.

STORE AND “FORGET”

Amazon Web Services’ Glacier archive (and backup) was introduced about five months ago. With Glacier, users can reliably store large or small amounts of data for as little as $120 TB per year, a significant savings compared to on-premises solutions. There are some small download bandwidth charges, too.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Fig. 1

Using hard-drive (not tape) technology and some tricks to reduce power and wear, Glacier appears as an “object store” for up to many 1,000s of terabytes of data. The generic headaches associated with Nos. 1–5 in Fig. 1 now belong to Amazon’s staff, not your technical staff. Offloading these pain points is a huge advantage. This is the “forget” part of this column’s title.

Glacier is a cloud service and like other cloud resources, the complexity of managing, upgrading, maintaining, powering, cooling and more is offloaded to the cloud provider. When a storage resource (drive, array) fails, Amazon deals with data migration to the new store not you. In practice, this can go on for many years, covering several generations of aging storage devices. Nice.

Additionally, Glacier offers a 99.999999999 percent durability guarantee (No. 3 in Fig. 1). Durability is a measure of the integrity of your data. What does eleven 9s of durability mean in practice? Although not specifically stated by Amazon, it likely means four to six copies of your data spread across different storage systems and geographical regions. Some consider eleven 9s excessive. However, a “two belts” and “two suspenders” approach makes sense in a world with Hurricane Sandy and its effects occurring more often.

PRACTICAL ISSUES

Nothing is perfect and there are two concerns for most users: availability and access delay. Availability (R/W access to your data) is typically 99.99 percent (one hour/year). Don’t confuse this with durability. For example, if your Internet access connection to the cloud is down for two hours, your data is not lost, just not available. This is manageable and not that different from many on-premise solutions. Incidentally, using multiple ISPs to access the cloud reduces the chance of connectivity loss.

Also, many cloud vendors permit one and 10 Gbps network connections, so datarate throttling is not strictly a barrier. Also, as an option, some cloud vendors support importing/exporting large amounts of data to their storage using mailed-in portable storage devices: USB/SAS/SATA drives. This is ideal when huge quantities of data are involved.

The second aspect is access delay. Glacier trades off read-access delay to reduce monthly cost. The current spec is three to five hours for file recovery to start. Some may balk at this since an on-premise LTO library has faster access. But Glacier is designed for long-term archive like the physical records stored by Iron Mountain offering 24-hour retrieval. If your workflow can absorb the three- to five-hour delay, then Glacier may apply. The three- to five-hour delay does not reduce the instantaneous retrieval data rate. Once started, file-delivery rates can reach many gigabytes per second.

This new class of archive will likely be implemented by other cloud providers. My intention is not to market Amazon products, but to reference Glacier as a new product class in the arsenal of the cloud. LTO is alive and well and will continue to take the lion’s share of on-premise archive. A Glacier-type archive may find a niche in “primary-archive backup” or “delayed-retrieval” archive space.

There is one more objection to a Glacier- like cloud archive: the dependability of the vendor. Do I trust the cloud vendor with my data? Will they go broke and leave me hanging? These are legitimate questions. Trust is something that needs to be earned; it takes time. So, as cloud vendors build trust, our industry will decide what assets and services to offload to them.

We are at about “year six” of the cloud, and still taking toddler steps. Each year all constituents are learning more with service integrity, security and dependability increasing and prices dropping.

So, will you eventually use something like Glacier to store your crown jewels? The clear trends say yes. The question is when and it may be sooner than we think.

Al Kovalick is the founder of Media Systems consulting in Silicon Valley. He is the author of “Video Systems in an IT Environment (2nd ed).” He is a frequent speaker at industry events and a SMPTE Fellow. For a complete bio and contact information, visitwww.theAVITbook.com.