Remembering Telstar

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

WASHINGTON: In today’s world where pizza pan-sized satellite antennas delivering hundreds of television channels are as common as starlings on rooftops of homes, businesses, and even RVs, few recall a time when receiving video from space was just a dream.

Fifty years ago—July 10, 1962—that dream became a reality in a big way with the successful launch and activation of Telstar I and people from all nations of the earth taking notice as the United States, France and England exchanged television programs in real time for the first time.

GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY NEGLECTED?

Half a century tends to dull memories and little is planned in the way of commemorating this once momentous event. The French embassy, in conjunction with the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum is planning an afternoon program, the Coalition for American Solar Manufacturing [photovoltaics powered this first transatlantic satellite video relay] sent out a commemorative press release, and the Governor of South Dakota issued an executive proclamation declaring July 23rd as “Telstar 1 Anniversary Day” [scenes from Mt. Rushmore and Custer State Park were transmitted via the new satellite 11 days after it went into service]. Aside from this, there’s not much else planned to commemorate that day in 1962 when the world became a great deal smaller.

Telstar’s launch was a giant news event in its day—it served as the vanguard for all wideband satellite communications that came later. The event even inspired a song that made it to the top of the pop music charts in both England and America. However, on its 50th anniversary, the bird and its launch seem to have been all but forgotten.

People working in television in the 1960s and ’70s will certainly remember the significance of satellite-delivered television—the long lead-time booking of transponder access, the coordination process and setup time with the commercial carriers and the few uplink/downlink facilities in operation then (in the beginning, these were not co-located with television stations, or even network facilities), and also the great costs associated with satellite video. And when the technology was in its infancy, broadcasters used supers and announcements to make sure that viewers knew when programming was being relayed by spacecraft.

Huge horn antenna at the AT&T Andover satellite ground station at Andover, Maine, used to communicate with the Telstar.

“Satellite television is just something taken for granted now,” said Hal Wallace, curator of the electricity collections at the Smithsonian. “I remember watching signs on TV in the 1960s that said ‘live via satellite,’ and that’s just not done now.”

Wallace acknowledged that the Telstar 50th anniversary had even slipped by him and his department.

“We did an objects-out-of-storage exhibit recently—the theme was 1950s and ’60s—and I pulled out some transistors for it,” said Wallace. “There was a display board from Bell Labs showing the variety of transistors used in Telstar I, but I really wasn’t aware of the anniversary coming up.”

SETTING THE SCENE

For those who don’t remember, or weren’t there, Telstar really was the big news item of the day. Even President Kennedy, speaking during a scheduled press conference, lauded the efforts of thousands of scientists, engineers, and factory workers in turning a dream into reality.

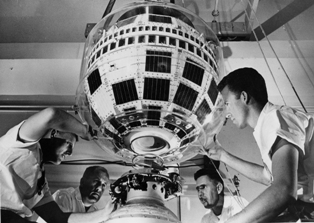

Technicians prep Telstar for launch.

“I understand that part of today’s press conference is being relayed by the Telstar communications satellite to viewers across the Atlantic, and this is another indication of the extraordinary world in which we live,” President Kennedy said. “This satellite must be high enough to carry messages from both sides of the world, which is, of course, a very essential requirement for peace, and I think this understanding, which will inevitably come from the speedier communications, is bound to increase the well-being and security of all people—here and those across the oceans.”

At precisely 6:35 p.m. EST, all three U.S. television networks interrupted scheduled programming for a live cut-in demonstrating this incredible new capability for sending moving images across 3,500 miles of the Atlantic Ocean. France initiated the relay with an eight-minute program transmitted from its Pleumeur-Bodou earth station and featuring a musical performance by Yves Montand and Michele Arnaund, along with remarks from France’s post and telecommunications minister, Jacques Tarette. (Rather ironically, the French satellite salute came via videotape, as the transmission occurred after midnight Paris time.)

Transatlantic Video Before Telstar

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Once television established itself in the late ’40s and early ’50s, carriage of news and other special events programming quickly became a common desire of the networks. [In 1953, CBS went to great efforts to get kinescope recordings of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II back from London and on air in the States the same day it happened, going to the extreme of chartering an airliner and stripping out most of the seats to make room for flatbed film editing stations. The program was assembled as the aircraft crossed the Atlantic.]

Prior to the launch and activation of Telstar I, the only way to get full bandwidth video across the Atlantic had been via airline delivery of videotape. Slowscan television images could be sent via existing submarine telephone circuits (which themselves were only about six years old at the time of Telstar’s launch), but these left a lot to be desired in terms of entertainment value.

In the pre-satellite era, one proposal for exchanging live video back from Europe called for “orbiting” a number of aircraft at fixed stations over the Atlantic for microwave relay purposes. As one aircraft returned to base for refueling and a fresh crew, another was inserted into its position, providing an almost continuous video transmission path. Fortunately, perhaps, this idea was never put into practice. From an historical perspective, John L. Baird had succeeded in sending low-resolution video via shortwave radio from England to America in 1927. And in 1938, BBC “high definition” 405-line low-band VHF broadcasts were received in New York; however, this was due to a propagation “freak” and could not be counted upon for any sort of regular service.

The Telstar venture was the natural culmination of man’s desire to view unfolding events at great distances.

- James O’Neal

“Relax, you are in Paris, I invite you to spend a few pleasant moments with me,” advised Tarette, who used the event to praise French-American cooperation.

Several hours later—the French program, soon after it began, ended with loss of acquisition of Telstar—England was next to go up with a 12-minute program uplinked from its own Goonhilly Downs satellite facility.

Unfortunately, a behind-the-scenes squabble mired the beginnings of this new era in communications, with the British accusing the French of breaking an EBU agreement that specified that the first Europe-to-America feed was to be a joint venture.

Regardless of the politics, millions of Americans that evening were astounded to see and hear television programming originating from across the big pond. The satellite had been launched from Cape Canaveral on July 10, with initial activation and testing of its wideband transponder capability taking place some 15 hours later on July 11. Engineers at Goonhilly Downs and Pleumeur-Bodou got their first glimpse of American video with a shot of the Stars and Stripes flying outside the U.S. earth station, accompanied by “The Star Spangled Banner.”

The U.S. earth station forming the nucleus of this historic relay was located in Andover, Maine, and as in the case of the U.K. and French facilities, was selected primarily for its proximity to the Atlantic in order to shorten the distance between stations and thus maximize the amount of time available for transmissions during the satellite’s availability every 2.6 hours. (Telstar was not a geosynchronous bird; that didn’t happen for another two years and the launch of Syncom II.)

Telstar’s transponder capacity was extremely limited by today’s standards—about 500 voice telephone circuits, or one TV channel, and its power output was in the neighborhood of 4 Watts, requiring huge antennas and liquid-cooled amplifiers to pull the received signal out of the noise. Once acquired, its transponder capability was only useful for about 20 minutes at a time, with signals fading into a sea of noise as the 16,000 mph satellite traveled out of range and could no longer be tracked by the earth stations.

Thor-Delta 11 launched Telstar on July 10, 1962.

THE TELSTAR LEGACY

AT&T put more than $50 million [close to $400 million in today’s currency] into the development of the Telstar communications satellites and paid NASA an additional $4 million to launch it. Telstar was a small satellite by today’s standards—less than three feet in diameter and weighing only about 170 pounds. And the first Telstar placed in orbit had an unexpectedly short life.

The day before Telstar’s launch—and in an apparently uncoordinated effort—a couple of U.S. government agencies had placed a 1.4 megaton nuclear warhead into low earth orbit and detonated it as part of an experiment known as “Starfish Prime.” In addition to frying street lighting systems and an inter-island telephone microwave relay in Hawaii, the resulting radiation also burned out transistors on Telstar I, taking it temporarily out of service five months after its launch, and permanently disabling it in February 1963. However, Telstar did fulfill the dream of its Bell Labs designers, ushering into existence the era of live television from anywhere on the planet (and later from the moon and other parts of the solar system).

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.