Moore’s Law may have reached a limit

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

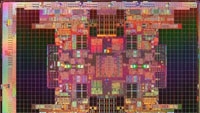

For decades, Moore’s Law has ruled the manufacturing process of electronic devices. Coined by Gordon Moore, a founder of Intel Corp., the “law” stated that the number of transistors that could be housed on an integrated circuit chip roughly would double every two years.

Using this law — actually it’s more like a rule of thumb — the electronics field has been revolutionized over the years. In broadcasting, professional color television cameras were downsized in less than 40 years from nearly the size of a Volkswagen automobile to smaller than a fountain pen.

Moore’s Law has affected everyday life — including a huge range of electronic products. Millions of people walk around with smart phones far more powerful than the personal computers of only 20 years ago.

Now, according to a report in the “New York Times,” researchers fear that this extraordinary acceleration is about to meet its limit. The problem is that squeezing more transistors into smaller spaces requires too much electricity, which also causes the electronic devices to overheat and ultimately fail.

“It is true that simply taking old processor architectures and scaling them won’t work anymore,” William J. Dally, chief scientist at NVidia (a maker of graphics processors) and a professor of computer science at Stanford University, told the newspaper. “Real innovation is required to make progress today.”

The problem was described in a paper presented in June at the International Symposium on Computer Architecture. The most advanced microprocessor chips today have so many transistors that it is impractical to supply power to all of them at the same time. Some transistors are now left unpowered, which is called “dark silicon.”

As early as next year, these chips will need 21 percent of their transistors to go dark at any one time, according to the researchers who wrote the paper. In three more chip generations, as many as half of them will have to be turned off to avoid overheating.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Doug Burger, an author of the paper and a computer scientist at Microsoft Research, expanded on that thought to the Times.

“I don’t think the chip would literally melt and run off of your circuit board as a liquid, though that would be dramatic,” Burger said. “But you’d start getting incorrect results and eventually components of the circuitry would fuse, rendering the chip inoperable.”

This may mean the level of innovation many people have come to take for granted will no longer happen or at least dramatically slow down. In their research, Dr. Burger and fellow researchers simulated the electricity used by more than 150 popular microprocessors and estimated that by 2024 computing speed would increase on average only 7.9 times.

By contrast, if there were no limits on the capabilities of the transistors, the maximum potential speedup would be nearly 47 times, the researchers said.

Still, chip designers have been struggling with power limits for some time. The industry hit a wall at around three gigahertz when chips began to melt. That has set off a frantic scramble for new research, and while the room is there for new ideas and designs, so far, nothing adequate has come of it.