Mastering DTV viewers

The DTV transition is now 10 years old. In the first half of 1997, the FCC adopted the ATSC standard for DTV broadcasting and established the rules for the DTV transition, which was supposed to end Jan. 1 of this year.

The FCC's transition schedule was placed on hold thanks to an amendment to the 1997 Budget Act. The amendment required 85 percent of homes in a market to be able to receive DTV broadcasts before a broadcaster would be forced to return its NTSC channel.

Last year Congress passed another budget amendment that established Feb. 17, 2009, as the end date for NTSC broadcasts. The bill also authorized the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) to develop a subsidy program for digital-to-analog converter boxes that will allow existing NTSC receivers to work with DTV broadcasts. (See “Web links” on page 18.) Beginning in January 2008, consumers will be able to obtain up to two coupons worth $40 each toward the purchase of these NTIA approved, but severely crippled, converter boxes, which are expected to sell for $60 to $75.

In June of 1997, ACM's netWorker magazine published an article in which I was highly critical of two things. One was the process that created the ATSC standard. Second, I criticized broadcasters who lacked — and still do — the vision to develop and deploy a DTV system capable of bringing the broadcast industry into the 21st century. (See “Limited Vision: The Techno-Political War to Control the Future of Digital Mass Media” in “Web links.”) Such a system would have allowed broadcasters to fully use the digital processing capabilities and standards now commonly used by consumers in new generations of computers, handheld devices and the TV set-top boxes deployed by competitors in the DBS and cable industry.

The computer and Internet services industries I supported throughout the process to develop the ATSC standard lost that battle. Ten years later, other than HD and the ability to multicast several linear channels, broadcasters have little to offer in terms of features and services that could make over-the-air television a viable business for the future.

The NTIA converter box program is a missed opportunity. Rather than developing a new digital platform capable of enabling new market opportunities for broadcasters, it keeps the NTSC laggards firmly locked into the linear past.

The opportunity to develop more capable DTV receivers and set-top boxes still exists. One example is an HD-capable receiver with a personal video recorder. Broadcasters, however, have not shown interest in evolving beyond the tired old formula of delivering linear program content that is overstuffed with commercials. These commercials are often inserted using another relic of the 20th century, the master control switcher.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The team I backed may have lost that battle, but it is winning the war, at least in terms of defining the technologies and standards being used to deliver digital media content to the masses. The media conglomerates, which still have a stranglehold on the distribution of high value content produced by Hollywood and college/professional sports franchises, have shown little interest in updating their broadcast operations and those of their affiliates. Instead they are turning to the Internet to develop new business opportunities, just as their viewers are turning to the Internet to download content and access news and information that broadcasters simply do not make available in a relevant manner. Consumers are learning that they can access what they want, when they want it. They also know they can consume TV content anytime, not just when it is broadcast.

Multiplexing objects for local composition

A decade ago, much of what I wrote in “Limited Vision” was theoretical. The notion that a broadcaster could rely on a TV receiver or set-top box to handle functions that have traditionally been relegated to the master control switcher was too big a leap from the old linear time and channel programming model. The concept that the receiver should be the point of composition of content from multiple sources, including the Internet, was nothing less than the ranting of a heretic.

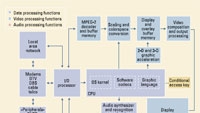

A decade later, consumers rely on this new model of local object composition routinely via Web browsers. A Web page is delivered as a group of objects, often from multiple servers that insert ads, or handle the more complex task of streaming real-time video. These objects are composed for presentation using powerful graphics chips that handle video scaling, antialiased graphic overlays and transitions, including fades, dissolves and digital effects that required expensive broadcast digital video effects systems in the early '90s. (See Figure 1) This computing and graphics processing power is now moving to handheld devices and new generations of boxes that connect to the big screen in the family room.

The technologies and standards needed to put a master control switcher in every television in your market are not only available, but also they are cheap. In addition, they can solve a variety of problems with the traditional way that DTV facilities have been designed, while providing a platform broadcasters could use to develop new revenue streams. An added benefit of delivering objects (files) to DTV receivers is that stations could realize a major improvement in compression efficiency. This helps maintain quality while freeing up bits for new revenue-generating services.

Consider something as commonplace as a fade to black or a crossfade between two video streams. This stuff drives entropy-based compression algorithms like MPEG-2 and the newer MPEG-4 part 10 (H.264) video codec nuts. When a fade takes place in a station's master control switcher, the encoder must try to deal with the fact that there is no redundancy in each successive frame of the fade. The result is often more like a fade to block than a fade to black.

The fade can be performed in the receiver by sending a few bytes of data instructing the receiver to fade out the current stream. Crossfades can also be accommodated by sending both streams and letting the receiver do the transition.

How about those annoying logo bugs? Where do you insert the bug so that it can be seen on all televisions in your market? If you put it in the lower right corner of a 16:9 program, viewers watching your station on one of the new NTIA authorized boxes will not see it, as only the 4:3 portion of the program will be displayed. If the bug is placed in the 4:3 safe area, it will be in the wrong place on 16:9 screens. If the bug is sent as an overlay object, it can be placed in the correct location for any display, or the viewer could elect not to display it at all.

The ability to implement such features is not difficult. The MPEG-4 standard provides the tools for all of these features and much more. An HTML browser integrated in the receiver could do many of these tasks and bring the Internet to the big screen in the family room.

What is lacking is the will of broadcasters to let go of their linear past and become part of the new digital information infrastructure. In place of the master control switcher, a server would deliver program streams and other services as part of the station's digital multiplex.

Far more important, commercial breaks could offer capabilities that are impossible when a station creates a linear stream for the encoder. For example, multiple commercials could be delivered simultaneously, and the receiver could pick out the commercial to display based on locale (zip code) or content (demographics). If this sounds overly complex, consider that this is already happening on some cable systems using off-the-shelf set-top boxes with MPEG-2 decoders.

Visible World developed the authoring tools and headend server technology that has been delivering highly customizable commercials for several years. (See “Web links.”) The system sends out multiple streams using different PIDs in the MPEG2 transport stream along with composition metadata. The receiver uses the metadata to compose different versions of the commercial based on market localization or demographic requirements. The headend gear can overlay time-sensitive information when the streams are played out.

Broadcasters need a viable platform

The ATSC is busy again developing a standard for mobile, portable and handheld devices. There is a parallel effort to add new compression capabilities to the standard to serve these devices. H.264 is likely to be authorized for new services that will be delivered to these new mobile, portable and handheld devices.

It's a start, but it misses the target by a wide margin. Broadcasters need a well-defined platform that supports the services needed to compete in the 21st century. Failing to do so could leave broadcasters at a competitive disadvantage as content moves to the Internet and is delivered to competitive platforms. These platforms will make those old analog TVs look more like a 19th century light bulb than a 21st century information appliance.

Craig Birkmaier is a technology consultant at Pcube Labs, and he hosts and moderates the OpenDTV forum.

Web links

- NTIA Digital-to-Analog Converter Box Coupon Program www.ntia.doc.gov/dtvcoupon

- “Limited Vision: The Techno-Political War to Control the Future of Digital Mass Media,” ACM netWorker, June 1997 http://www.pcube.com/pdf/limited.pdf

- Visible World www.visibleworld.com

Send questions and comments to:craig.birkmaier@penton.com