150 Cameras and Counting

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

TURTLETOWN, TENN.

A lot of us are collectors. For some it's coins, stamps, or maybe match books. Others, operating on a somewhat grander scale, with a passion for gathering together objets d'art or perhaps classic cars.

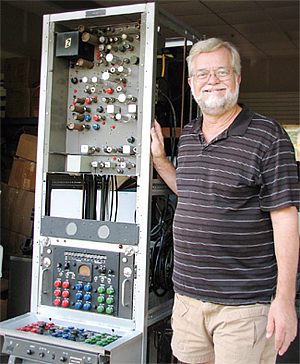

Chuck Pharis poses with one of the many television cameras he's rescued from the dumpster. Chuck Pharis is one of those who collects on a grand scale; however it's not cars or paintings, but rather television cameras—broadcast type cameras. Pharis has been collecting them for 40 years and isn't finished yet.

"I pulled my first camera out of a dumpster behind a TV station in San Francisco," said Pharis. "This was a Norelco PCP-70. This was probably in 1970, or pretty close to that. The thing was a nightmare, but I decided to keep it."

Pharis estimates that he now has more than 150 broadcast cameras in his collection. They range in size and weight from the awesome RCA TK-40 (with a 44-inch long body and weighting more than 300 pounds with viewfinder, lenses, and handles attached), down to RCA's first ENG offering, the TK-76 (handheld and weighing a mere 19 pounds).

The cameras in Pharis' collection date from the late 1940s and include monochrome and color models from virtually all manufacturers, including Ampex, DuMont, General Electric, GPL, Marconi, PYE, the Radio Corporation of America, and even one very special model from Zenith.

"That camera was used to demonstrate high-definition television to the FCC in the early 1990s," said Pharis. "Zenith made just a few of them then and the de-velopment costs were over $800,000. I got this one courtesy of Wayne Bretl [principal engineer at Zenith Electronics]. They not only sent me the camera, but also several crates along with it—manuals, racks, spare tubes, spare preamps; all sorts of things to go with it. I got home and there were seven giant pallets full of equipment waiting for me. I was able to get the camera up and running within a few weeks."

FROM TINSELTOWN TO TURTLETOWN

Pharis' cameras came from all across the country and are now under one roof at his home in this small southeast Tennessee town (population 1,546). Actu-ally, Pharis has been a resident of Turtletown for only a matter of months, having grown up in Southern California and spending most of his lengthy career in broadcasting in the Golden State.

"After 40 years in the business, I decided that it was time to get out of California," he said. "I needed space to set up my collection and land here is a lot more affordable here than in Los Angeles. There's also no crime, no smog, and a lot of beautiful scenery. It's just a great place to retire."

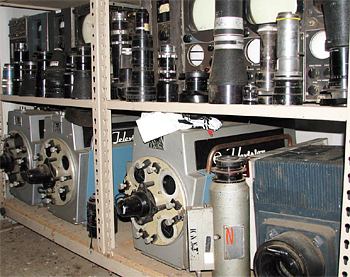

These RCA TK-60 cameras, along with lenses, power supplies and monitors await full restoration. Pharis has enough vintage video gear to supply the studio needs of a large 1950s television network operation. Pharis said that he homed-in on Turtletown after searching online for a location that met his requirements. Early this year, he found a custom-built home and nine-acre parcel of land that seemed ideal for his purposes, and was on a plane shortly afterwards to inspect the property first-hand. Soon, four large trucks loaded with tons of broadcast gear were on their way from Los Angeles to this tiny town situated about an hour and a half from Chattanooga.

For now, most of Pharis' cameras, lenses, tripods, pedestals, CCUs, viewfinders and other gear are packed away like cordwood in an existing storage barn lo-cated a few feet away from his new home. But he has plans to break ground shortly on a much larger building that will allow him to properly spread out his treasures and set them up in an operating environment. He envisions ultimately creating a museum devoted to equipment used for electronically capturing images.

"My goal is to share this vintage broadcast equipment and the history behind it with anyone who is interested," said Pharis.

NOT JUST CAMERAS

Pharis' collection is not just limited to television cameras; as like so many in the broadcasting, he got his start in radio.

I started college in 1964 and the school had a radio station," Pharis said. "I was always interested in electronics and got a DJ position there and started taking broadcasting classes."

This first career step, and Pharis' proximity to the Hollywood film and television industry, may account for a large microphone collection that complements his cameras. It spans some seven decades of microphone evolution, and includes many classic examples of carbon, condenser, ribbon, and just about any other technology that can be used to convert sound into electricity. Along with the mics are several large examples of early audio mixing gear. These consoles are also slated to be restored to operating condition and placed on display in Pharis' museum.

This recently acquired CCU and "Colorplexer" is the missing link for restoring to operation one of Pharis' RCA TK-41 three-IO color cameras. He also has an extensive collection of television-themed children's toys, including cameras and remote production vehicles. In another area of his home, are a number of industry awards, including three Emmys. Pharis spent the majority of his career as a senior video engineer with the ABC Television Network in Hol-lywood, working on a number of studio productions including "American Bandstand," "The Lawrence Welk Show," and "Welcome Back, Kotter," and also spend-ing time in the field with ABC Sports.

"I did lots of sports events while at ABC, including four Olympics," he said. "Since I retired from the network in 2003, I've been working on a contract basis with ESPN doing college football."

In touring Pharis' relocated, and currently somewhat concentrated collection, it's difficult not to ponder the scope of events and subjects that some of these lenses and tubes have captured—especially the early RCA color cameras, which in the beginning of the NTSC color era were sold in very small numbers due to their cost (more than $500,000 in today's currency) and were generally reserved for special programs, due to extra costs involved in operating and maintaining them, as well as the expense in staging color productions for the very limited number of color receivers in viewers' living rooms. In addition to the very early TK-40, Pharis seems to have cornered the market by amassing an additional five TK-41s, a slightly improved version of the 40, but which retained its physical profile and weight.

The most recent of the TK-41s had arrived shortly before my visit and included an element that's often missing when early cameras are unearthed—the camera control unit, or CCU. Pharis' latest find also included what RCA termed a "Colorplexer." Today, we'd call it an NTSC encoder. The camera chain is 100 percent complete and in its original operating configuration—something that is nearly impossible to find today.

"This is something that I'm really proud of; probably the one thing that I'm most proud of, as it's 100 percent complete," said Pharis. "This will be my first working TK-41. Hopefully I'll have it up and running within the next year."

Items are packed together so tightly in the temporary storage facility that it's sometimes difficult to pick out rare items without first being alerted to them by Pharis. An exception to this was a large pale green hood-like affair reposing on the concrete floor. Pharis hefted it, explaining that it was part of an early video "recording" scheme created by Allan B. DuMont.

Before the invention of videotape recording, the only way to capture a television show was by photographing images from a CRT screen onto motion picture film. Image quality from these "kinescopes" was generally poor and DuMont wanted a better way to store studio programming created at his fledgling network. The result was the "Electronicam," a hybrid television/film camera, which contained an optical relay system that split incoming light to both a television pick up tube and motion picture camera. The film camera "saw" the same thing that the television tube did, and when the film was processed, all that remained was to reassemble individual segments back into a high-quality film print of the live production. This was aided by tally lights tied to the video switcher, which marked the head of the film take when the camera was put on-air by the TD.

"This one was probably used to record 'Captain Video,' Pharis said. "I have the original manuals for these. DuMont made both a 16mm and 35mm version. Jackie Gleason used the 35mm version for 'The Honeymooners,' as it had better quality."

Even though Pharis rejoices in his discovery of a complete TK-41 camera chain, he has unearthed another item upon which he places an even greater value, as it is truly one-of-a-kind. And this item was created with paper and ink; not wires and electron tubes. It's not stored with the cameras, but rather locked away in a safe place.

In Part 2, Pharis explains how the most prized item in his collection—the original 1938 signed artwork for the ubiquitous RCA "Indian Head" test pattern—was rescued from a pile of trash headed for a landfill.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.