A Pattern for Testing

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

TURTLETOWN, TENN.

A generation or so ago, a certain male figure graced television screens in countless millions of homes in America. His visage was not exclusive to any one station, or even to a single network. He never received any compensation for his daily appearances, and no one is even sure if he had a name. Yet, he was as well known as Milton Berle, Captain Kangaroo, or Buffalo Bob. And like one of the denizens in Buffalo Bob's stable—Clarabell the Clown—he never spoke, not even on his last on-air appearance.

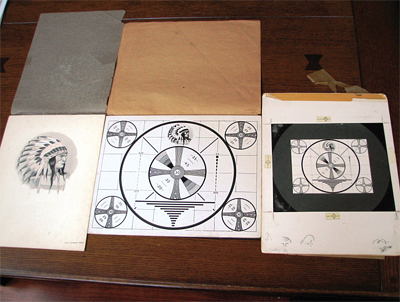

This is the original “Indian Head” drawing from 1938. The slight coloration in the feathers and other areas is due to oxidation of the paint pigments after more than 70 years. During his run, he was simply referred to as "the Indian-head," or just "the Indian." Today he'd be referred to as "the Native American," but political correctness wasn't really a big part of the U.S. landscape 50 or 60 years ago.

The figure was that of a Native American chieftain, complete with his feathered war bonnet, and if he were a real being, he would have turned 72 this past August 23. This was the date in 1938 that an artist identified only as "Brooks" completed his or her drawing of the figure. It had been commissioned by the Radio Corporation of American, and presumably "Brooks" was paid for the work shortly after its completion. The thought of a continuing royalty on a "per use" or "per appearance" basis, rather than a one-time payment, must never have been considered, as "Brooks" would have been set for life from practically that moment on.

(Even the mighty Radio Corporation of America didn't sense a lot of potential dollar signs in the artwork back, as they allowed the copyright to expire somewhere along the line.)

RCA had chosen the figure to adorn its latest television test pattern, and in a little more than a year after the Brooks' drawing was delivered, the completed pattern was ready for "prime time," if anyone could have used that term to describe television in 1940, the year that marked the first on-air appearance of the "Indian Head" test pattern.

Brooks' artwork now resides in something of a Mecca that offers homage to RCA and other early television equipment manufacturers. This particular shrine is maintained by one Chuck Pharis and has been relocated from Hollywood to this very tiny and remote southeastern Tennessee town. Pharis' goal is to create a public museum centered around restored broadcast cameras from television's early years. And the Indian Head image will certainly be spotlighted, as it represents a type of "camera" that predates the earliest studio camera in Pharis' collection.

The Indian Head test pattern, as seen on millions of American TV screens, was not televised via a studio camera, or even in the form of a "slide" scanned by a television "film chain." It was actually the nucleus of a special camera that was devised in the 1930s and used extensively to wear and tear on studio cameras, lights and the several racks of tube-type support equipment needed to put a live picture on the air.

Chuck Pharis and the original RCA Indian Head test patternA CAMERA WITHOUT A LENS

This unusual "camera" took its name from the tube that created the test pattern or other image, the monoscope sometimes referred to as a "monotron." (The Dumont organization had its own version of the tube and gave it a rather sinister sounding name—"Phasmajector.")

The Indian Head test pattern soon became a television icon and was literally moved inside RCA's monoscope camera tube. (For those not familiar with the monoscope, it appears very similar to an ordinary small cathode ray tube—narrow neck with electron gun at one end and a flared "screen" area at the other end. However, there is no phosphor screen; just an aluminum plate inside the tube, with the image to be televised printed in special ink on that plate. Instead of exciting phosphors, the electron beam scans the printed image and a small electrical signal corresponding to blacks, whites and mid-tones is taken directly from the plate.) Most early stations had monoscope cameras tucked away in a rack somewhere where they ran 24/7. The Indian Head appeared on a generic test pattern, but for an additional fee, RCA would customize it with a station's call sign, city of license, channel number and other information. They sold a camera—the TK-1A—that used this tube to a very large number of early TV stations.

Pharis, as do some other collectors of early television gear, has several monoscope cameras tucked away with his studio and field models; however, he has something else in his collection that is strictly one-of-a-kind. This is the original artwork commissioned by RCA more than 70 years ago.

And there's a story behind the artwork. According to Pharis this sacred icon of the TV cult nearly wound up in a New Jersey landfill.

THIRTY YEARS IN HIDING

"In the 1970s, construction workers were demolishing a building at RCA's Harrison [N.J.] tube operation," Pharis said. "RCA removed everything they wanted, leaving the rest for the demolition contractors to dispose of. One of the workers had a load of ceiling tile to discard and when he opened the closest dumpster he found it full of paper—TCA artwork. The guy was a little curious and skimmed off the top layer. He took this home and found the Indian artwork. Everything else went to the dump."

Pharis says that the contractor was familiar with the Indian Head pattern, having seen it, like many of his generation, on almost a daily basis on TV. He decided to hang on to it and put it on a closet shelf where it remained for some 30 years.

"He was getting ready to sell his home and move into a rest home and his son was helping him clean out the house," Pharis said. "The son decided to research the Indian Head on the Internet and came across my web site which features a reproduction of the test pattern. We made a deal and he sent me all of the remaining papers and artwork."

The box that he received not only contained the Indian Head drawing, but also the component parts of the test pattern—concentric circle drawings, resolution wedges and the like.

"This is really the Mona Lisa to me," said Pharis. "If you look carefully, you can see the slight hole in the paper the person who drew this made with their compass."

He soon had the drawings authenticated by an art expert who verified that it was the real thing.

These historic items almost wound up in a New Jersey landfill. "In the original 1938 Indian drawing you can see what looks like a little bit of color," said Pharis. "Actually that's due to the paints used back then. One of them must have had a little iron in it and it's so old that this is oxidized, adding a slight amount of color."

Pharis decided to make the artwork available to other vintage television enthusiasts, and after checking for a copyright (it was by then in the public domain), had the material copyrighted and scanned at a very high resolution by a friend, Pete Fasciano. Fasciano later developed some variations on the original test pattern theme—one of these is a 16:9 aspect ratio version—and Pharis makes a complete package available via his web site. He has also sold the test pattern packages at several NAB Shows. The demand for "the warrior on a test card" still runs high. Pharis estimates that he has delivered more than 1,000 copies to lovers of early television lore.

"The people who want them are mostly in this country, but I have had several orders from outside the U.S.," he said.

DESPERATELY SEEKING 'BROOKS'

Early on, Pharis tried to contact the obscure "Brooks." He followed several leads as to the artist's identity and location, but got nowhere. He eventually contacted the PBS "History Detectives" to see if they could ferret out "Brook's" identity.

"They went crazy over this stuff," Pharis said. "They spent six months trying to figure out who 'Brooks' was, and why the Indian head was used, but just couldn't crack the case. They did locate the original technical data for the Indian Head test pattern and sent me a copy, but that's as far as they could go.

Pharis says that he considers the Indian Head artwork to be the crown jewel in his large collection of television-related artifacts and plans to hang on to it. "However, I am thinking about passing it along to the Smithsonian when I'm gone," he said.

The Indian Head artwork and some of Chuck Paris' video camera collection may be viewed on his Web site, www.pharis-video.com.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.