NEW YORK—This column is the wrap-up to a workshop I moderated at the AES Convention last October with panelists Jeff Brugger of Turner Studios, Michael Cardillo from Creative Waves, television mixer extraordinaire Ed Greene, and Sean Richardson, principle audio engineer at Starz. The proposition of the workshop was that delivering mixes for television has become substantially more complicated with the large number of outlets content is delivered to and the deliverables required by each outlet.

Where we once simply sent a mix to the primary air chain, they can now end up in places we never dreamed, after going through file manipulation processes over which we have little information or control. In addition, wide dynamic range surround mixes designed for broadcast are impractical in just about every situation outside the living room, and preparing content for the mobile world and low bandwidth connections may require modifications to channel configuration, bit rate, codec and loudness settings.

Jay Yeary (L) moderated “The Changing Audio Deliverables for Broadcast and Media” workshop at the 2015 AES Convention, which included panelists (L to R), Jeff Brugger, Sean Richardson, Ed Greene, Michael Cardillo. With loudness specifications for streaming just beginning to be sorted out, it’s still a little like the Wild West for content once it leaves the traditional broadcast path. With ATSC 3.0 bringing immersive 3D-like soundfields to the home, including more than 100 channels to manipulate, even broadcast deliverables are becoming more complicated. The following is a distillation of my key takeaways from the workshop.

Mixes Will End Up in Places We Never Dreamed—Longform content generally has the longest lifespan so it should end up in more places than promos and short-form content, but all content will be heard in more places than we think. At minimum, content will be heard on broadcast, cable, network websites, OTT, theatrical advertising and international outlets.

Due to limited time and budgets, (and our inability to foretell the future), it is impossible for a mixer to create a different mix for each outlet, so mixers should provide the best mix possible for the known outlet(s) and not sweat the others.

If the Mix Sounds Bad, Make Some Noise About It—Taking the time to listen to a mix on the primary outlet may unearth problems that a broadcaster or content outlet is unaware of and will help ensure that what’s on the air sounds as close as possible to the way the mixer intended. It can be a bit of a hassle, and no broadcaster wants to get problem calls, but if the content is not airing properly, it will also bother viewers, not just the mix engineer.

Delivery Specifications Are Critical—Broadcasters spend a lot of time developing content delivery specifications with the intention of airing content without modification of the original. Ensuring content meets the broadcaster’s specifications will save everyone a lot of grief.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Particular attention must be paid to channel configuration to guarantee the proper audio shows up on the correct channel in the air chain. Not all broadcasters use the same 5.1 channel layout and some still require delivery of content with Dolby E. Adherence to loudness specifications will keep content from being rejected for incorrect loudness levels or for exceeding True Peak values.

OTT Deliverables Are Different— Over-the-top and streaming deliverables are different because many devices can’t handle multichannel, don’t have the headroom for wide dynamic range content, or are used in noisy environments where the only possible way the content can translate is when the gain is raised and headroom is reduced.

In October 2015, the AES released technical document TD1004.1.15-10, “Recommendation for Loudness of Audio Streaming and Network File Playback,” which recommends that streaming loudness not exceed –16 LUFS nor be lower than –20 LUFS, with peaks not to exceed –1.0 dBTP. In essence, the AES appears to be advocating –18 LUFS as the overall target for streaming loudness, 6 dB higher than the target for broadcast loudness, yet the True Peak value gives back only one of those decibels for headroom. Sessions requiring additional deliverables for OTT may not have additional time booked so it may require the mix engineer to output multiple mixes at the same time.

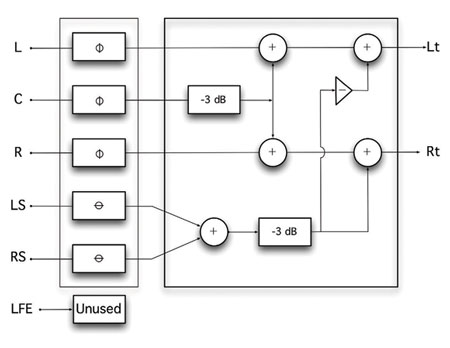

The Lt/Rt DownmixMost People Only Hear Two Channels So Always Check the Downmix—Despite 5.1 systems being in homes and immersive audio on the way, most people still listen to television through two speakers, either because they don’t have multichannel setups or because their location dictates a minimal listening environment.

This means that the two-channel version of a mix is significantly more likely to be heard than the 5.1 version. If 5.1 is the only specified deliverable, mixers should pay careful attention to how it will sound when downmixed.

It is always best to deliver a separate two-channel mix for air everywhere that isn’t 5.1, but some broadcast air chains can’t deliver separate mixes to the home so it has become critical to listen to the downmix of all multichannel mixes and make adjustments to the original if the downmix suffers.

Lt/Rt and Lo/Ro, There Is a Difference—Lt/Rt stands for left total/right total and is a method of matrixing 5.1 mixes into a two-channel version. Lo/ro means left only/right only, in other words, a straight two-channel (stereo or mono) mix.

In order to provide a full-time surround image to viewers, some broadcasters have specified Lt/Rt as their two-channel deliverable in the belief that it will upmix better to 5.1 than pure stereo mixes, which is generally true as Lt/Rt starts with 5.1 and tries to provide an approximate reproduction of that mix when decoded.

Accomplishing this first means throwing away audio from the LFE channel, so any important sound in that channel should be mixed into the Left and Right channels. Left and Right are each separately summed with Center, which has been lowered by –3dB. The Left and Right surround channels are summed together; then added to the Left/Center sum at 180 degrees out of phase, and to the Right/Center sum at zero phase. Needless to say, all of this channel combining, gain adjusting and phase shifting is not what mixers generally want for their mixes.

Unfortunately, this process is typically done automatically in the broadcast air chain rather than being part of the mixing process, so many mixers would prefer it go away and have outlets broadcast Lo/Ro instead, forgoing upmixing entirely.

Jay Yeary would like to thank Jeff Brugger, Michael Cardillo, Ed Greene, and Sean Richardson for their willingness to share their experience and insight at the workshop that was the basis for this column. Jay can be contacted through TV Technology magazine or attransientaudiolabs.com.