Assessing the State of 4K/UHD in Today’s Broadcast Ecosystem

4K creates technological and operational challenges, especially as bigger events demand higher levels of gloss

The move to high definition didn’t make viewers work hard to notice the improvement. It was easy to promote, in TV showrooms or at broadcast equipment conventions.

The shift from HD to UHD is almost as big a jump in linear pixel count, and while the same level of immediate uptake probably wasn’t expected on the consumer side, broadcast clients have begun demanding it almost as a matter of course.

It’s no surprise to see an outside broadcast truck covering an event in 2023 with “UHD” as a proud part of its livery. Sometimes that’s done for future-proofing, and sometimes to satisfy early adopters at home. Whatever the motivation, UHD creates technological and operational challenges, especially as ever bigger events demand drive for ever higher levels of gloss. That increasingly means high dynamic range and UHD, always with the pressure to somehow do it all with the same resources as conventional HD.

Future-Proofing

There are now a number of ways to do that, and many of them diverge from the sort of technology that broadcast has long been used to. Arri’s Multicam system marries its Amira camera—itself not quite a UHD device, but usually near enough—with a fiber adapter and compatibility with the sort of control panels and other truck tech that put engineering people in a place of comfort.

Similar things are possible even on lower budgets with equipment from Blackmagic Design, which not only has cameras with studio accessories and lots of spare resolution, but also switchers, recorders, and the Resolve application.

Sony has also put its high-end cinema cameras into the parts of broadcast which seek to bring a little Hollywood sparkle to live TV, although by sheer hours broadcast, the company’s more conventional studio cameras are still doing the lion’s share of the work.

Peter Sykes, strategic technology development manager at Sony in the U.K., confirms that the motivations for UHD are “a combination. The future-proofing part is very, very important, because prestige content will be archived. Especially for sports events, archive is a consideration once you get to the top tier events… if you want to put something in the archive, do it at the highest quality.”

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

It wasn’t just the technology that needed to be addressed, but fitting the technology into existing workflows was a challenge."

Peter Sykes, Sony

In the immediate term, though, the pressure to please subscribers remains key. “The image quality is something people will look at when they’re trying to differentiate themselves from their competitors,” Sykes confirms. “You can get the consumer TVs, and the bitrates are available as they weren’t in the very early days—but if you have a premier league football game, the rights for that game are very, very expensive and you need a good look. They’re always trying to get the best rights, and that’s a way to differentiate.”

It’s been over a decade since Sony launched its first 4K broadcast camera, though Sykes points out that HDR had to wait on standards activity.

“Live broadcast producers were operating in an HD SDR environment, mainly, and our first developments looked at increasing the resolution,” Sykes said. “As a follow-on stage about a year later, in the mid-2010s, HDR in live production really started to capture everyone’s imagination. It was the ITU which developed the specifications for TV production. When those arrived the pathway was opened up to start producing live content, and that’s where HDR really did capture everyone’s imagination.”

It’s Not Just the Technology

Equipment is one thing; technique is another. “There is a technology aspect to all this,” Sykes confirms, “but there’s also an operational aspect to it as well. It wasn’t just the technology that needed to be addressed, but fitting the technology into existing workflows was a challenge. Imagine you have outside broadcast companies with operators in the trucks, camera shaders, vision supervisors, all having lots of experience in HD SDR, to then come along and say we can’t have two trucks, we have to have a simultaneous workflow so we have some new practices, but we don’t want to have to completely retrain.”

Automatic downconversion is one option—once a picture has been engineered for HDR, there’s enough consistency for a machine to create the accompanying SDR output.

“If you look at some of the work the BBC has been doing, they’ve developed their own LUTs, and we’ve also issued some LUTs of our own, which are freely downloadable from our website to do conversions from HDR to SDR.”

Sykes concludes, though, with the observation that while truck technique is key, dealing with large sensors and high resolutions demands the best of camera operators, too. “If you’re going to shoot the halftime show at a major event, you’re going to put your exceptionally good talent on that.”

Ready For Anything

Blackmagic Design’s approach to high-resolution broadcast came from slightly different beginnings. Darren Gosney, technical sales manager for the company, begins on a technical note:

“We were one of the key manufacturers driving for 6- and 12-gigabit SDI technology across a lot of live products,” Gosney said. “We wanted to move away from dual and quad link for high bandwidth content. One of the things we’ve really pushed for is UHD for HD prices—all the way back to when we launched the first ATEM switcher with 6G SDI capabilities, 10 years ago.”

“What that’s let us do is to allow not only high-end broadcaster to work in UHD, but also other people to experiment,” he added. “What we’ve noticed over the past 10 years is where that’s bled into other areas, the AV and live events workspace. If you’re hosting live music events or high-end concerts, you’ll have huge LED walls at the side of stages and in those instances high resolution is beneficial. If you’re pumping through low-res content it’s hard to distinguish what’s going on.”

High Frame Rates

On smaller screens, some of the most tech-savvy consumers exist in the world of computer gaming. High-bandwidth workflows were adopted early to satisfy viewers who demanded high frame rate, if not high resolution.

ome of the earliest applications for images beyond traditional 25- or 30-frame broadcast standards were targeted at applications other than broadcast. Esports needs high frame rate for much the same reason that conventional field sports need high frame rate. It’s the same reason 720-line 50- and 60-frame formats existed, and it’s why 1080p60 pictures have since become an everyday occurrence.

Even before 60p became common for live sports broadcasting, gaming tournaments often meant putting together 3Gbps infrastructure to handle live cameras and feeds from both the player monitors and in-game virtual cameras. Still, pushing resolution beyond HD meant four physically separate links until 6- and 12-gigabit SDI, or more recently various IP options, found ways to fit UHD pictures down a single cable.

“Esports is a huge emerging market,” Gosney says, “and has been for the last few years. The technology there sometimes exceeds what you’d see in broadcast. We’ve done extensive work with the likes of ESL, a big esports conglomerate across Europe. They use capture cards to get content in and out of workstations.”

The company’s Ursa Mini cameras, with their Super-35mm sensors, are examples of a multipurpose approach that’s only recently become commonplace; big sensors with lots of resolution which can be cropped to suit the job at hand.

“We’ve used the really powerful sensor we had in our other 6K camera so that you have the dual-ISO capability, which is really good in low light if you’re in a conference center, or for darker concerts,” Gosney says. “Because it has the resolution, you can also put a B4 broadcast lens on there and go shoot an interview, then shoot the VTs which are interspersed with the live production… that is one of the huge benefits of that camera.”

Much as the Ursa series is perfectly capable of shooting HDR images, Blackmagic’s implementation through its switchers is a work in progress. It’s a reminder that HDR is a system, not a product, although the company is well-placed to build that system.

“Other manufacturers do cameras, or switching, or routing, but we have every part of the puzzle,” Gosney says. “We can connect end to end and it gives customers confidence that things will work cohesively. Things like the ATEM ISO lets you run a fleet of 4K cameras through our HD television studio switcher, and it’ll record an iso feed in low bandwidth H.264. Then, you’ve got the option to drop that into post, cut, then relink to the camera originals working in 4K or 6K or even higher.”

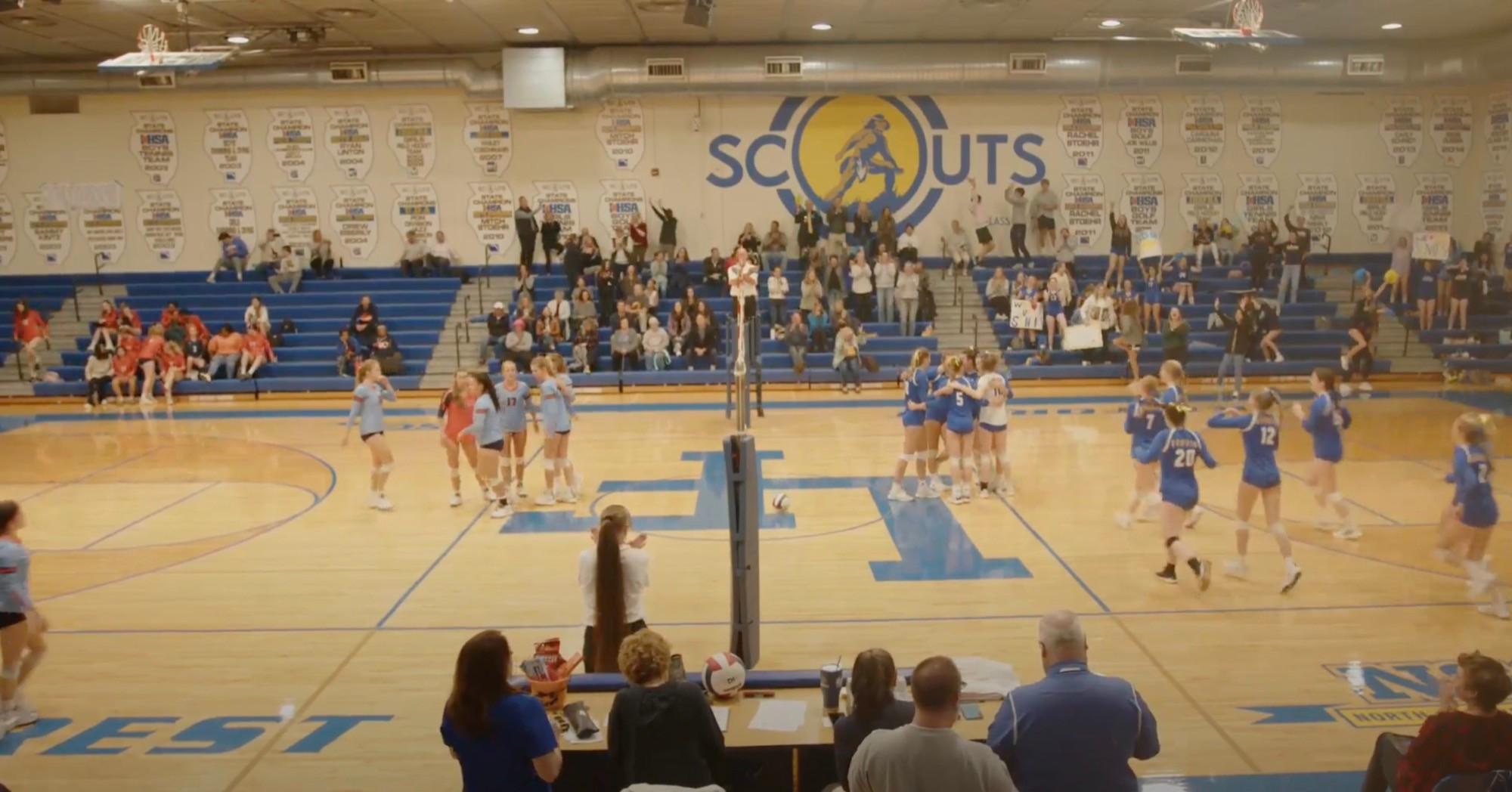

With that sort of capability available even from the company which positions itself as the affordable option, the offset between what producers want and can have, and what the audience is actually watching, seems set to persist or even widen. With the technology democratising, though, the best conclusion might be that it may not matter that much, because if we want UHD and HDR at 60 frames, we can increasingly have it, from high school sports to the Super Bowl.