Content File Logistics, in the Cloud

It's been a year now since I personally took the leap into the unknown realm of entrusting all my data to "the cloud". Of course, like a good engineer I have backups, just in case. But so far, I haven't had to call upon the backups to get me out of trouble.

More of note in the same period of time is how the subject of cloud computing has steadily raised its profile in our industry news headlines and in the discussion forums. The general feeling I get, and it seems to be shared by others, is the anxiety associated with letting go of the 'safe' old way of storing our media.

When will keeping a videotape library at a TV station be like keeping all of one's money stuffed in a mattress at home? The same kind of anxiety was felt when we first moved from pure videotape operations to hard disk servers within our production plant. It happened in the edit suite first. The Abekas disk recorder led the way. Then we saw the Tek profile used as a 'cache' on the output of a Sony LMS, Ampex ACS or Odetics TCS. It was initially quite a scary thing to entrust the advertising revenue to a new and more or less unproven device like the Tek Profile and all the servers from other manufacturers that followed.

But it only took a couple of years for the servers to win our vote of confidence and totally supplant the videotape cart machines for the storage and playout of commercials and promos. Moore's Law held true while an almost exponential expansion of hard disk capacity and performance brought us to the tipping point where the servers took over the role of playing out all the on-air content, including long form programme material.

Now it's happening again. We are all feeling somewhat out of our comfort zone when we think about having the entire library of content in another company's hands. But I think it's an inevitable outcome. In the not-too-distant future, keeping a videotape library at a TV station might be likened to keeping all of one's money stuffed in a mattress at home.

We already entrust our wealth and cashflow to the computing 'cloud' within the banking system. We outsource the safekeeping of our personal valuables via safety deposit boxes. There's no doubt in most people's minds that the banking system can protect our physical cash and other financial instruments better than we can at home. Our wealth, both personal and corporate, already exists entirely as files of one kind or another in the IT infrastructure of the banking and finance community.

Given the rapid growth in supply of bandwidth and storage capacity, concurrent with drastic ongoing cost reduction for those things, only one question remains: has the tipping point been reached? Have the curves crossed? Has the downward trending Cost curve crossed the upward trending Capacity curve at a point where both are now viable for a broadcaster or production house? Can we get enough bandwidth and storage capacity at a cost that makes sense for a migration from the old way of doing things?

This question can now be answered in the affirmative. And the business case for it will only get better and better as the cost of storage and bandwidth continues to decrease. Driving the declining costs is the recent advent of the one stop shop.

Last year, we had to lease the network from one vendor, and the IT storage and the virtual server from another vendor, and license the application software from yet others. For example, in Australia, the network vendor might be Telstra or Optus and the cloud storage and server could be rented from Amazon and the application software might be Rhozet Carbon Coder. This year, in Australia, we can rent all of it as a single package service from Telstra or from SohoNet. Other vendors will enter the one stop shop business soon. And every country in the region will have its equivalent vendors.

We are copying the logistics service providers who handle physical goods. Major manufacturers have been outsourcing their transport and warehousing and even packaging of parts and completed products for decades. Logistics companies like DB Schenker, Panalpina and Kuehne & Nagel have made healthy billion dollar businesses by taking care of end to end transport and storage of goods on a global scale.

Technicolor is to videotapes what DB Schenker is to Apple iPads. Technicolor established itself as a one stop shop to pick up videotapes, or even film, from Hollywood, do the telecine transfer if needed, do a standards conversion if needed, and duplicate to many copies if needed, and finally deliver to the TV station. That videotape logistics business is now beginning its transition to a file based model. International data circuits replace ships, planes, trains and automobiles. IT servers in data centres replace warehouses.

Sony DADC has been in that kind of business for decades in the world of music CD and movie DVD production and distribution. The copyright holder gives a master tape to Sony DADC. Then Sony DADC presses millions of CDs from that master tape, prints the CD jacket, packages the CD and printed jacket into a plastic CD case, and boxes them onto racks or pallets in a warehouse, before shipping them off to retail outlets. The first time the copyright holder of the music sees a physical CD is probably when he or she visits the local music shop. There's no need to be involved in all the production and transport steps of the CD.

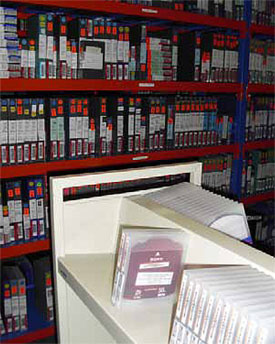

Videotape library as anachronism

In this new era of economics, where the physical is being replaced by the virtual, in-store is being replaced by online, CD racks in a music store are being replaced by a list of titles in the iTunes application, book stores are being replaced by Amazon and its competitors, a videotape library in a TV station is fast becoming an anachronism.

If we extrapolate the observable trends, our crystal ball might show a playout system in a TV station five years from now directly accessing the needed content in its daily playlist from an online server in an external data centre managed by an outsource service provider.

What inhibits that crystal ball vision is the fact (or belief) that the original content from Hollywood isn't suitable for direct broadcast. It needs processing. That processing involves editing of various kinds and quite commonly the addition of captions, and transcoding to a lower bit rate if the playout servers have limited bandwidth or capacity.

This processing that occurs to bring the original Hollywood content into a form that is acceptable for local broadcast is what complicates the vision of the future. The master files from Hollywood need to be 'refined,' for lack of a better term – somewhat like the way crude oil passes through an oil refinery to make diesel, petrol and kerosene.

In a TV station, upstream of the playout system, we need to design and establish a "content refinery" to distill the various forms of content that we need from the original Hollywood master. Defining those refinery processes and automating them, or enabling human control of them in a computer domain is largely the business of MAM – Media Asset Management.

From a user's perspective, MAM operations are performed entirely at a computer desktop workstation, with the exception of ingesting videotape from the legacy videotape library. Once the content is in the form of a computer file, there's no further physical contact with that content for the human operator. And that's why the platform for MAM operations, or the "content refinery" need not be physically within the broadcaster's building. It could all be hosted externally by an outsource service provider, like SohoNet, or Technicolor, or RedBee, or someone else.

This isn't a new idea. Britain's biggest telco, BT, put together a system a few years ago to provide a service called "Mosaic" which was a remote login service for MAM operations. The Mosaic service is an assembly of many applications and products from dozens of suppliers. When Tata Communications bought the Mosaic business from BT in January, 2010, their press release included this statement: "The acquisition of the Mosaic platform strengthens our global media and entertainment portfolio with powerful cloud-based digital media management applications that can be accessed over the Web."

So there it is, the term "cloud-based" in the same sentence as "digital media management" and "over the Web". And that was more than two years ago. Some momentum must surely be building. There is a way now. If it isn't happening everywhere, it's most likely due to a lack of will. The opposite to "a lack of will" is "an enthusiasm to proceed." And that enthusiasm to proceed is generally dampened, or even killed, by the sheer scale and complexity of the task.

It will cost millions. It will require a contract. And the contract must be based on detailed technical documentation. In this author's recent experience, the documentation is the stumbling block. Getting consensus on the myriad of details and documenting it clearly and making sure it is totally correct is no easy task. And the number of people currently working in TV stations who have the required skill set for the task is quite small. The devil is in the details, as the saying goes.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.