Avoiding the Digital Cliff is Harder

Now that the U.S. government has avoided the Fiscal Cliff and reached some type of financial agreement that citizens have been told we should be happy about—even though it will increase our taxes and social programs will be cut—it’s time to look more closely at another nagging precipice that, I suggest, personally and directly affects many more people. I’m talking about resolving the country’s more monumental task: the broadcast industry’s digital cliff. There’s no solving it, mind you, due to current technical and age-old physical limitations, but maybe we can minimize the negative effects on viewers with better technologies and more efficient use of spectrum.

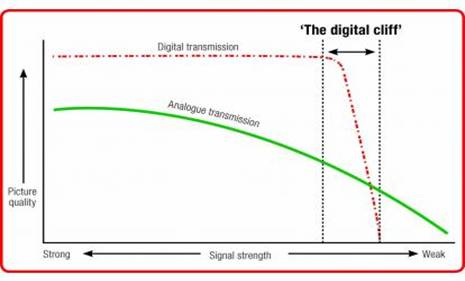

In the days of analog TV, reception was accomplished in varying degrees, depending upon where you lived. But you always got some type of image on the screen. [I vividly remember watching the 1969 Mets win the World Series in an apartment building in Queens, NY on a 13-inch black-and-white TV via a very “snowy” picture.]

Somewhat similar to what members of Congress have gone through the past few weeks, today’s broadcast TV engineer is struggling with how to make his constituents (e.g., TV viewers) happy while also having to answer to behind-the-scenes influencers (station management) set on cutting costs. Forget the Fiscal Cliff, broadcast engineers fear what’s know as the “digital Cliff Effect”: that is, the video data falls off the proverbial cliff of visible picture information. Reception at the TV set is either accomplished successfully or it isn't. There is no in between. You might see a frozen picture or nothing at all. [On February 18, 2009, when analog transmissions were shut off in many markets, the FCC received more than 25,000 calls from consumers complaining of no TV reception.]

In digital broadcasting, this cliff effect is mostly often experienced by over-the-air TV viewers living in mountainous areas and in urban cities with large buildings, as well as the fringes of local stations coverage areas—all places where signal prorogation can be problematic. Satellite TV subscribers also suffer due to the phenomena. While forward error correctionis often used to address the problem, when a minimum threshold of signal quality (a maximum bit error rate) is reached, there is not enough data for the decoderto recover. This often causes the picture to break up (pixellation), lock on a freeze frame, or go blank. Causes include rain fadeor solar transiton satellites, and temperature inversionsand other weather or atmospheric conditions causing anomalous propagationon the ground.

This cliff effect is also a serious issue for local stations building out mobile DTV channels, as engineers in many cities are finding that signal quality varies significantly when moving round a DMA. According to engineers who have field-tested Mobile DTV reception, the cliff effect is most often experienced if the receiver is moving rapidly, like when driving in a car.

While the country’s Fiscal Cliff has been avoided, it’s clear TV engineers have to a lot more to contend with. The difference between what Congress accomplished and what has yet to be conquered in television might be like comparing night and day, but when the underappreciated-until-the-signal’s-not-there infrastructure goes over that “cliff,” consumers/viewers—many who rely on TV for comfort and security as well as entertainment—suffer all the same.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.