The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of the most eye-opening and simultaneously disheartening experiences I’ve ever had as an audio engineer happened during an AES Atlanta student workshop where I was volunteering. Jim Anderson, multiple-Grammy winner and jazz recording engineer extraordinaire, was teaching the class on critical-listening that day, discussing frequency ranges of instruments, ear training, and getting the participating high school and college students to concentrate and understand what they were hearing. Toward the end of the class, Anderson would play samples of work he had recorded in the studio to compare original mixes against compressed versions of the same songs.

It was a truly glorious experience to hear a well-recorded, high-quality, uncompressed mix from a professional studio, crafted by a masterful engineer.

Everyone in the room listened intently as the versions were played and when Anderson asked the students which they preferred, I naturally assumed everyone would choose the original. To my utter horror, many preferred the lower bit-rate compressed version. While some of the compressed files sounded quite good, others were lacking upper harmonic content and had a collapsed soundfield compared to the original.

As I discussed this experience with other engineers present at the event we pondered whether the students had ever heard real instruments or whether they were so accustomed to modified and effected sounds that that was now their preference. It also left me wondering if anyone cares about quality anymore and whether it has been displaced by convenience.

Old vs. new mediaCASH SOMETIMES TRUMPS QUALITY

The broadcast world is not immune to this phenomenon with viewers more concerned about the ability to consume content anywhere instead of how it looks or sounds. As the industry struggles with how to broadcast 4K, consumers are increasingly using small screens for viewing. While immersive audio is conquering cinema and promises to make its way into homes, consumers pop buds into their ears or listen to tiny tablet speakers, sometimes while sitting in the same room as their large screen television and home entertainment center.

Anyone who has seen the signal degradation that occurs when an MVPD needs to cram more channels into their lineup quickly realizes that cash sometimes trumps quality. Broadcast channels divvy up their frequencies to provide as many channels (and revenue streams) as possible rather than provide a best-quality experience. The FCC used to require that broadcasters meet rigid standards and that broadcast engineers be licensed. Now the agency seems more concerned with filling government coffers through auctions and fines, which leaves industry groups like the ATSC, SBE and SMPTE creating standards and hoping for compliance.

Oddly, the protagonist of all this fragmentation is the very thing that initially promised to yield improved quality—digitization of data. The way we’re able to manipulate video and audio these days is almost magical, and digitization has allowed us to do and create things that were impossible in the past.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

When compact discs were released, so were we—from scratches, dirt in grooves and poorly pressed vinyl. Yet digitization also ushered in the age of pirating and sharing of content and it also brought us data compression. Digital, by its very nature, is merely a sampling and reconstruction of the original, but it still is not the original. This facsimile-state is true of uncompressed, high bitrate, high-resolution PCM audio and it is even more so for lossy compression schemes such as AC-3, AAC and MPEG. Lossy compression tosses out more of the original and tries to recreate it with whatever data has been retained, so keeping the sample rate and bitrate high are absolute necessities for decent quality audio with these codecs.

iPad Mini stereo speakers atop one small speakerIS IT REAL OR IS IT COMPRESSED?

There are countless psychoacoustic studies explaining that people cannot discern the differences between uncompressed and high bitrate compressed audio files; and there is little doubt that most people can’t hear the difference, but mostly because they don’t stop and take the time to really listen. However, I wonder if we’re conditioning ourselves to hear differently when virtually everything we listen to is sliced, diced, tossed out and then mathematically sewn back into some form of the original for our listening horror.

One of the ways increased bitrate reduction is justified is that our brains mask errors and fill in the gaps when we listen. This proves our brains are marvelous information processors, but should we be forcing them to do all this extra work simply because we’re being stingy with bits?

At the content creation end of the chain we spend money to ensure mix engineers listen on properly set-up surround systems, yet the majority of home systems come with speakers that have a limited frequency response, so the system relies on the subwoofer to handle everything the rest of the system can’t. That puts a lot of audio content into a speaker that should only be reproducing low frequencies.

Some living spaces can’t accommodate surround speakers, so we install products such as soundbars to provide pseudo-surround, and, in the future, immersive audio will surely bring us products with pseudoimmersion. Yet even these are better than the speakers in most flat-panel television cabinets, which often come with their own special version of surround emulation.

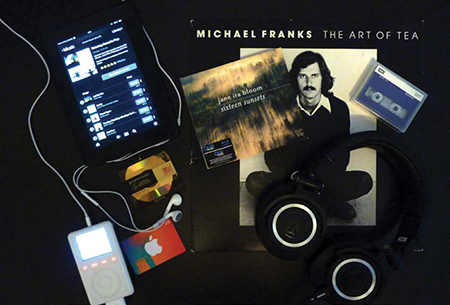

Like other parts of today’s society, the world of audio has become polarized. High quality has lost out to convenience in some areas, but there are also signs of hope. Vinyl is experiencing a resurgence among music lovers and bands are selling uncompressed downloads of their albums. Sales of highquality headphones are increasing and live music opportunities seem to be everywhere.

Television, however, seems stuck in the model of throwing away bits of audio as we compress the video, even though 5.1 mixes take up 1/100th the space of 1080i video (0.013824 Gbps at 48 kHz, 24 bit vs. 1.485 Gbps at 60 Hz, 29.97 fps). We’re still forced to compress everything for over-theair broadcast delivery, but with ATSC 3.0 in development and broadcast-over-IP in our future, perhaps it’s time to reconsider whether we want to continue throwing away the best bits of the content we deliver to consumers.

Jay Yeary is a broadcast engineer specializing in audio. He is an AES Fellow and is a member of both SBE and SMPTE. He can be contacted via TV Technology.