Cutting to Picture for Impact

Now in my 30th year writing this column, this has been a great opportunity to report on the latest editing technology, shine a spotlight on some of the most talented practitioners of our craft, and indulge in the dissection of the greatest examples of the art and craft of editing.

Over the years, my attempt to understand the aesthetics of the editing craft has provided the most challenging quest for this column. We know editors have three great tools at their disposal: context, contrast and rhythm. But whether the final cuts in a sequence are determined by the editor, director, writer or producer, in addition to appreciating the “hows” of editing, post-production, pros can also advance the discussion when editors gather around the ol’ campfire of discarded floppy discs by comprehending the “whys” of editing.

RHYTHM OF THE AUDIO

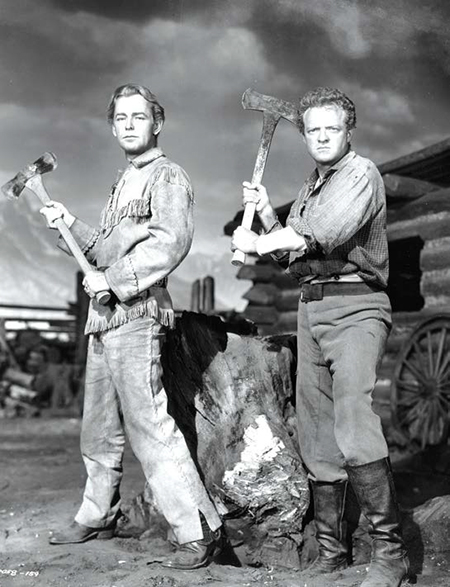

Alan Ladd (L) as Shane and Van Heflin as Joe Starrett in the movie “Shane”

Most of the time, experienced editors know that you usually cut to the rhythm of the audio. That can be either cutting (or cutting around) dialog or action, and the reason for this leads us to ask, “Why are we able to perceive an edited sequence at all?”

Instead of a coherent stream of images, why don’t our brains simply receive a succession of disparate shots? After all, in music, the notes, percussions, harmonies and counterpoints enter the brain as a continuous flow. So why does our vision permit, in fact yearn for, a continuity imposed on visual sequences derived from the sum of their whole?

That’s because ears don’t blink.

Watch a person’s eyes and you will see them darting from one angle to another—up, down, left, right—constantly in motion. Yet our brains do not receive “image-black-image” or “image-swish-image.” It constructs a coherent appreciation of our perceived surroundings by discarding the visual information that falls below a threshold of comprehensibility during the instant of either a blink or an accelerated whip/pan. Sometimes this is called the “suppression of vision” to correlate with the “retention of vision” concept that creates moving images out of a sequence of stills presented in rapid succession.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

As a result, thanks to the suppression of vision our brains are continually melding a smooth flow of impressions from the jumbled mess our visual acuity either blends together or rejects unnoticed.

Audio, on the other hand, washes over an audience continually, undaunted by whether they actually want to hear a specific sound or not. The result is that we are very comfortable cutting to audio. But what would happen if we cut to picture? What if the images alone determined the pacing? Can that work at all?

Acknowledging we are stepping into the realm of the subjective I’ll be using as examples some classic sequences that have historically entered our legacy from a wide enough spectrum of audiences to allow us to advocate the “work.” But cutting to picture, i.e. letting the content of the visuals determine the pacing, can be a tricky proposition.

ICONIC PUNCTUATION

These days, about the only time we see pure images dominate the construction of an edited sequence is during PG-rated lovemaking scenes where editors dissolve away just before revealing the good parts. But they are in a titillating class of themselves.

One of the earliest examples of intentionally cutting to picture in a film that had international impact comes in the first segment of Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 silent classic “The Battleship Potemkin.” The opening chapter “People and Worms” depicts the flashpoint behind the maritime mutiny during the revolution of 1905.

Sailors are complaining their meat is rife with maggots. In the mess hall we see dining tables suspended on rope from the ceiling. Uniformed attendants pull them down into position, but Eisenstein is not satisfied in showing this with a single shot. Instead, the tables are yanked into position in a succession of four rapid, overlapping cuts. This editing technique, never seen before in silent cinema, must have left an unsettling impression on audiences of the day. But Eisenstein is only sowing the ground for a subsequent harvest.

He pays it off when later one of the galley boys picks up the dinner plate he is washing and reads the inscription, “Give us this day our daily bread.” Enraged, he raises the plate over his head and, in a quick series of seven or eight again over-lapping shots (I think one cut is caused by a broken negative), smashes it down on the table.

There is no soundtrack to cadence the rhythm, but this cutting to picture slams home the sailors’ disgust with the food they are forced to eat, and capped by a quick fade out, provides an iconic punctuation to end the first part of this archetypal paean to the art of editing.

UNDERSTANDING THE POWER OF EDITING

Alan Ladd and Van Heflin in the scene chopping away at the stump.

Take as another example two contrapuntal scenes from the classic western, George Steven’s 1953 “Shane,” edited by William Hornbeck and Tom McAdoo.

After being offered a fine evening meal, the wandering gunslinger, Shane (Alan Ladd) notices a tree stump outside the window that the homesteader, Joe Starrett (Van Heflin) has been trying to clear from his land. In gratitude to the wife Marian’s (Jean Arthur) cooking, he takes up an axe and starts chopping away at the stump’s base.

Joe joins him and we are treated to a visual sequence of two men, whacking away side-by-side, helping to fulfill the dream of one while ennobling the other. Left/right, left/right, the axes tear into the wood in a succession of 20 or so edits, with the men pausing after the 16th shot to grin at each other in a moment we would now call male bonding.

This sequence is accompanied by Victor Young’s driving orchestral score, but watch it one time without audio and you will see that the juxtaposition of images compels the scene forward solely by the power of the alternating pictures, creating an impact that almost lets you feel the steel blades attack the obstinate wood. And once again seeds are being planted to be reaped in a subsequent scene.

Later, Shane is accosted by a scruff of range hands in Grafton’s Saloon being urged on by the grizzled cattle rancher Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer) who wants to steal Starrett’s land. Outnumbered, Shane is about to be beaten to a pulp when Joe Starrett, seeing the melee from the General Store, grabs a wooden bat and joins the fray. Again, fists fly left/right, left/right until Shane and Starrett find themselves back-to-back circled by the cowboys. They look at each other with triumph on their faces and the audience suddenly understands the symbolic significance of that lowly stump the two had previously conquered.

This time, Victor Young’s music only comes in toward the end and just as before, you can best appreciate the power of this pivotal scene with the sound turned completely off. The rhythm of the visuals demonstrates how effective cutting to picture can be in the hands of someone who truly understands the power of editing.

Jay Ankeney is a freelance editor and post-production consultant based in Los Angeles. Write him atJayAnkeney@mac.com.