Beyond mixing

From the manual switchboards and the early electro-mechanical automatic exchanges developed in the late 1800s, the telephone has evolved far beyond the imaginations of its inventors. A measure of this progress can be seen in the movies, where entire plots hinge on the telephone systems of different times, from the land-line alibi of “Dial M for Murder,” through the public hostage in “Phone Booth” to the virtual escape routes of “The Matrix.”

Today, sports and events production comms systems are following the trail of telephone systems into IP-based routing, with the implication that the rest of our audio systems and operations will soon follow. But the truth is that we are rather further behind the telecoms curve than we would like to think.

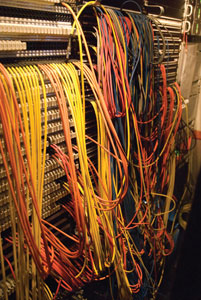

Today, facilities often try to avoid the type of “rat’s nest” shown here by relying on routers.

Looking back, it is easy to see how close early telephone routing and sound recording were. Not only did our patch bays resemble the bays of a manual switchboard, but the plugs we used were the same — and subtly different from the standard quarter-inch TRS jacks found on musical instruments and mixing boards.

We suffered from the same patching problems too — dirty jacks giving high-resistance connections, fatigued joints, connections lost whenever patch cords were disturbed. While with big monitor speakers, the studio “spaghetti” patch bay alongside the mixing board impressed the record company A&R man, it often frustrated the best efforts of the recording engineer to do the best job. The same frustrations were equally common in broadcast studios and OB vehicles.

A new paradigm

Not to be confused with digital networking, routing was one of the benefits brought about by digital audio. While sound purists debated the merits of different sample rates and bit depths, the practical advantages of digital routing were clear, although some were more evident than others.

With digital matrices taking care of routing, the immediate failings of mechanical patching systems vanished. In their place, digital routers allowed their inputs to be assigned to their outputs (even multiple outputs) at the touch of a button. This is exactly the same principle that underlies the first electronic telephone matrix switches, actually, as is the concept of central control. Yes, we still have patch bays in audio, but the spaghetti plate has been replaced by an impressionist painting — a few arcs of color that only allude to the complexity of the tasks they perform.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The digital audio matrix not only brings more reliable routing, it allows I/O configurations to be stored in memory and almost instantly recalled. It also allows control of routing and processing from a central operator’s position, eliminating the need to break from other operations to make changes or adjustments. To do this, its footprint has been transformed from a rack of jacks and cables to a panel in the console bay and pages on a system monitor. Apart from being tidier, it’s infinitely easier to read.

The digital router allowed its inputs to be assigned to its outputs (even multiple outputs) at the touch of a button. Its footprint was transformed from a rack of jacks and cables to a panel in the console bay and pages on a system monitor.

Better yet, a programmable system allows configurations to be moved independently of the equipment they served. It even allows configurations to be prepared away from the control room or OB truck. Before we follow telephone systems into packet switching and lP addressing, we would do well to understand the full potential of digital matrices — both their practical advantages and the benefits they bring to broadcast and live events.

A simple study of time spent against gains made in setting up a live mixing console or OB truck shows how a given setup for a manual system comes at the cost of time and/or number of operators. The immediate gains of a simpler, quicker and more reliable digital matrix are just the first step.

If a setup needs to be repeated, it can be carried over fully and instantaneously, with cumulative savings in time and effort. This offers obvious applications to regular television broadcasts, theater productions and live sports events.

In addition, a broadcast studio or OB truck that can be readily configured to serve different duties can be more productive, and profitable to operate, than one that requires hours to configure each time it takes on a different production. A truck that can be quickly reconfigured to provide its full potential range services can be used more frequently and in a wider range of applications than one that cannot.

The digital router core still resides in a patch bay, but the “spaghetti” has been replaced with fewer physical connections and flexible internal configurations.

In broadcast, as in live sound, renting a digital mixing console locally and configuring it from presets carried on a memory stick removes the logistical and environmental issues of shipping a large, heavy piece of equipment. In the same way, a single console can be configured to meet different needs and then updated as required during a program or event.

Stored configurations can even be passed from one sound engineer to another as they assume responsibility for a TV show, sports event, artist or tour.

Working offline is another concept that defies old analog systems. Preparing a system configuration ahead of time and away from a specific location can save time on-site and make good use of time that is necessarily spent in hotel rooms or traveling from location to location. This is equally true whether the travel is taking you between gigs or broadcasting a sports event from around the world.

Route of no return

So far, the advantages of digital matrix routing appear largely — although not exclusively — practical. There are, however, good business and peripheral gains here, too.

There are advantages in productivity and efficiency for audio operators, whether they are broadcast studios, OB services or live sound production companies, as well as cost savings.

There is the opportunity to review. After a broadcast ends, it can be reviewed offline to assess which aspects worked and which could be improved.

Finally, there are quality of work advantages. Freeing engineers from the physical duties of managing an analog patch bay offers savings in time, but freeing them from logistical duties and operational distractions also leaves them free to do a better job. From a company perspective, all of these considerations add up to better service for the client.

The future is likely to see IP step in, and the best use of the next development will follow proper understanding of this one.

—Felix Krückels is Senior Product Manager mc² series, Lawo.