Despite Fragmentation and Streaming, TV Syndication Soldiers On

The history of syndicated TV programs stretches back to the early days of broadcast television

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

First-run (originally produced by non-TV network studio content makers, aka syndicators) shows such as "Entertainment Tonight," "Jeopardy!," "Wheel of Fortune," "Oprah," "Dr. Phil," and "Judge Judy" plus off-network (reruns) shows such as "I Love Lucy" and "Star Trek" have captured TV viewers for decades. These syndicated shows are paid for by TV stations licensing these shows for cash, a mix of cash and national advertising slots reserved for the syndicator, or a barter arrangement where the syndicator and station split the national ad revenues generated by the shows.

Of course, much has changed since the Big Three (ABC, CBS and NBC) network days of the 1960s. In particular, the advent of independent UHF TV stations, Fox and other new networks, and then the plethora of specialty channels on cable and satellite TV, has fragmented the viewing audience. This fragmentation has been increased by Netflix, Amazon, Disney+, Hulu, and YouTube, among other subscription and ad-supported streaming content providers.

Despite this, TV syndication content producers and distributors such as Fox First Run ("You Bet Your Life with Jay Leno," "Pictionary," "25 Words or Less," "Divorce Court," "Dish Nation," "TMZ," and "TMZ Live") and Lionsgate’s Debmar-Mercury ("Family Feud," "Sherri," and "People Puzzler") are still producing current hits and developing new ones, while turning a profit in the process. Here’s how they’re doing it.

Sales Process Hasn't Changed

First things first: Although TV syndicators are mindful that the TV viewing audience continues to fragment even more, they’re not frightened by this fact. That’s because they’re accustomed to it.

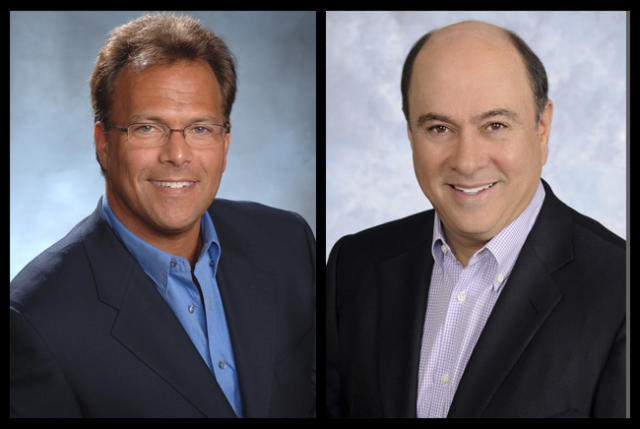

“Back in the 1980s, I was at an ad agency and I did a client presentation about fragmenting television and how cable television was going to disperse our audiences and take over everything,” recalled Ira Bernstein, co-president of Debmar-Mercury. “Since then, we've been through many, many stages where the audience just fragments more and more. So we’re used to it.”

“It's harder to get a large audience than it was before,” agreed Mort Marcus, Debmar-Mercury’s other co-president. “At the same time, the sales process for syndicated TV shows is much the same as it was 30 years ago. Granted, there’s way more business consolidation. Today a prospective client may own 50 stations instead of 10. Still, you’re selling TV shows on a city-by-city basis. And although the viewership has been compromised by fragmentation, local TV stations still need non-network content.”

The Economics Have Changed ... and They Have Not

With lower ratings due to audience fragmentation, it is harder for syndicated TV shows to earn the revenues they once did. “This is why the big time syndicated hits like 'Oprah'—which made so much money for distributors in the past because TV stations just had to have them—could be a thing of the past,” said Frank Cicha, executive vice president of programming at Fox Television Stations. “'Even Dr. Phil' is not going to do any more original episodes after 21 years on air.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

"That’s because viewership isn't supporting the idea of big license fees from stations as much as it used to—with exceptions like 'Wheel of Fortune' and 'Jeopardy!,' which remain as two legitimate hits," Cicha added. "Some would say that the days of the 10 million viewer talk show with the $30 million talk show talent are a thing of the past.”

This being said, first run TV syndication program production has never been a Cadillac industry. This is why its producers favor TV talk and game shows—both of which can ‘gang shoot’ multiple shows per day in studio.

“When it comes to our game shows, we typically shoot 180 shows over eight weeks, with two of those weeks off to pace things,” said Stephen Brown, executive vice president of Programming and Development at Fox First Run and Fox Television Stations. “It's good for the hosts because their commitment is only for six of those eight weeks, allowing them to do other things for the rest of the year. And it saves us money because we can use the same stage and crew for multiple shows, rather than setting up and tearing down after each one.”

Finding Other Revenue Streams

With the fragmentation-driven decline in their traditional revenues, syndicators are finding other ways to make money from their TV programs.

One way to do this is by franchising successful US TV syndication show formats to other countries. “For instance, game show formats like 25 Words or Less have been sold into Italy and Spain,” said Brown. “So we sell the shows, we sell the formats, and then there's streaming. When we can earn revenue from streaming shows like Divorce Court, that makes all the difference.”

Having the talent read commercials during the shows and offering paid product placements are two more ways that syndicators earn extra money from their content. Although there is debate about the additional advertising "clutter" these methods add to syndicated programs, “people generally understand that producers have to do this kind of thing or we're not going to get shows,” Cicha said. “I think it's that simple.”

Here to Stay

With their ability to produce cost-effective programming that people will watch, strike creative licensing and ad-sharing deals with TV stations, and generate a range of revenue streams from their content, syndicators are already accustomed to ‘living lean’. As such, they are better prepared to adapt to the economics of audience fragmentation than the big broadcast networks and streaming services are.

Moreover, “there will always be a need for content, especially for smaller stations that might not have a news division or lack the resources to produce original programming themselves,” said Brown. “So ultimately syndication is going to always be here. There's always going to be a need for our programming because stations need it.”

James Careless is an award-winning journalist who has written for TV Technology since the 1990s. He has covered HDTV from the days of the six competing HDTV formats that led to the 1993 Grand Alliance, and onwards through ATSC 3.0 and OTT. He also writes for Radio World, along with other publications in aerospace, defense, public safety, streaming media, plus the amusement park industry for something different.