Designing a Listening Room

As I threatened at the end of my last column, I'm going to devote some time here to the practice of Critical Listening, which is the listening you do to audio for money, i.e. professionally. In this column we'll talk about the room you need.

Yes, you need a room—pretty much all to yourself and big enough so others can join you on occasion. It should be reasonably well isolated acoustically, so that (a) you can hear your work without hearing anybody else's work or partying and (b) so that your work doesn't interfere with anybody else's partying or work. How such isolation is achieved is beyond the scope of this column.

What is also way beyond the scope of this column is why you need the various attributes I'm going to describe here. Trust me on this—they are based on some pretty good acoustical and psychoacoustical theory, as well as a lot of listening, both critical and otherwise, by me and many others, doing a lot of audio production work.

A SMALL ROOM

The room you use can be small. I'm assuming it will be rectangular. Minimum dimensions are probably about 8 feet wide by 10 feet long by 7 feet high (ca. 80 square feet area, 600 cubic feet volume). A more reasonable, still modest, size might be 11 feet x 17 feet x 8 feet (ca. 200 square feet area, 1,500 cubic feet volume). Bigger is usually a little better (up to about 40 feet), except that it will cost more to treat the larger surface areas.

SYMMETRY

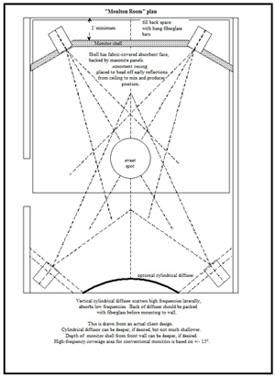

(click thumbnail)

Fig. 1 You would like the room and its layout and topology to be reasonably symmetrical along the long axis of the room. That long axis is what you should use for a median plane. A room that is all glass windows on one side and brick on the opposing side will be hard to work in, for example.

Happily, rectangular is good. It is best if length and width are not the same, or multiples of each other. Also, tricky shapes and angles are not needed for a listening room. Asymmetry is bad.

WALL, FLOOR & CEILING

In the simplest way of approaching the question of wall treatments, the front wall (the wall facing you from behind the speakers), plus the ceiling and the floor, should be absorptive (soft fuzzy surfaces), while the side and rear walls should be reflective (hard flat surfaces). Those hard surfaces can be drywall, plaster, wood paneling, etc.

As for the soft surfaces: the floor should be carpeted (best with a nice thick pad underneath the rug). For the front wall and ceiling, I recommend using a fabric-covered insulation material called UltraTouch (a humane replacement for open-faced fiberglass bats), from a company named Bonded Logic. I recommend the 5.5-inch thick version of it. You cover it with nice looking fabric so that it looks, well, nice.

Even if this is all you do to treat the room, you can obtain very good results. With this pattern of sound energy absorption (from in front, above and below) and reflection (from the sides and behind you), you will be able to obtain excellent stereo (and surround) imaging, reverberance and envelopment. It will be way better than just an untreated room with mostly reflective surfaces (especially the ceiling) or an overtreated room with absorption on all walls (especially the side walls).

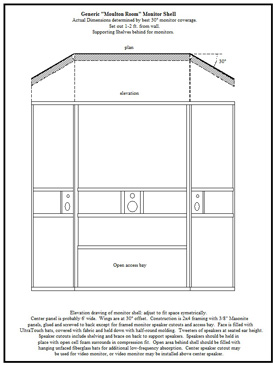

To go beyond this, we need to start worrying about low frequency (bass) absorption and standing waves. If you feel the need and have the budget, I recommend a "monitor shell" for the front wall of the room. This shell will house the loudspeakers and also absorb most of the low frequencies present in the room. It will also help with standing waves.

VENTILATION AND AIR HANDLING

(click thumbnail)

Fig. 2 Unfortunately, rooms in which humans work need ventilation as well as heating and/or cooling. Aside from the isolation problems such systems present, the forcible moving of air creates noise. Fan noise and air turbulence noise can be maddening and frustrating. It can also make production work extremely difficult. The standard architectural ducts, grates and fittings (a) usually are inadequate and (b) often make things worse. Oversize lined ducts, large baffles instead of gratings and air diffusers, and reduced air velocities are all desirable.

The really cheap way to solve this problem is called "time-sharing." Whenever you need to listen critically, you simply turn off all the fans. When you're done with that, turn 'em back on again. That simple! It actually works quite well.

The noise generated by equipment cooling fans is best solved by putting all such equipment other than the mixing console, the speakers and the computer keyboard and monitor in a separate machine room. If that's not possible, try a so-called "quiet box," which is nothing more than a carefully vented but isolated small rack for gear that can really reduce the ambient noise it generates.

Inconvenient as this truth is, the fact is that the room is an essential part of the loudspeaker. Damn! There's no such thing as a "good" loudspeaker, just a "loudspeaker that sounds good when placed a good way in a good room."

Therefore, we need to account for that room, in order to be able to hear reliably, accurately and well, the timbral, spatial and temporal qualities of our audio work. Only then can we begin to reasonably predict how our audio is going to sound to that vast range of end-users we affectionately call "our viewers."

Figs. 1 and 2 are drawings of a room topology I modestly call "The Moulton Room," descended from early Live-End Dead-End (LEDE) and Reflection-Free Zone (RFZ) rooms created by Don and Chips Davis, and Peter D'Antonio and Neil Muncy respectively. It's pretty cheap to build and not particularly dependent on specific room dimensions. Further, the monitor shell solves loudspeaker placement problems quite well for a wide range of small and medium-sized loudspeakers. The result is quite predictable and transparent playback that is extremely easy to work with for audio production. It also is a very pleasant sounding space, and generally enjoyable to be in.

Next column we'll take a hard look at the power and levels we need in order to listen critically, as well as what a good noise floor might be.

Thanks for listening.

Dave Moulton has a somewhat inflated median plane, and his image leaves a great deal to be desired. Other than that, you can complain to him about anything at his website, www.moultonlabs.com.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.