Thinking About Equalization: The Audio

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As you may or may not recall, I've been writing, ranting and raving about levels, loudness and compression in television broadcast for the past year. It's time for something else, because I can't stand thinking about it anymore.

Hence: equalization, also known as EQ. A clever bunch of controls that allow us to, ah, shape the timbre of our beloved audio signal. Before we dive into "Ten Easy Tips for Excellent Equalizing," however, we need to briefly review the concept of timbre and its relationship to the audio spectrum.

Timbre is an overly broad term used to describe the subjective attributes of a sound other than loudness and pitch. In fact, the definition of timbre is "all the things that allow us to distinguish one sound from another other than loudness and pitch." So, an immense number of things affect timbre, from how the sound starts to what the singer had for breakfast. For all that, one major determinant of timbre is the distribution of energy across the audio spectrum. And it is that physical distribution of energy that the process of equalization affects. As a result, we tend to think of EQ as "timbre control." This is a reasonable viewpoint, so long as we keep in mind that many other things affect timbre. Further, because we have equalizers, it is the determi-nant of timbre we can most easily control. So we do.

THE AUDIO SPECTRUM

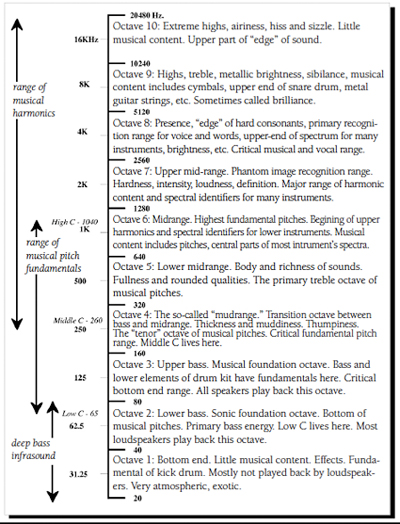

For this column, and some following ones, we'll be working on spectrum and equalization as they affect timbre or tone quality. The audio spectrum is the range of frequencies that we humans can hear. It is a comparatively large range: 10 octaves or 1,000:1. (Vision, by way of comparison, detects a range of only 1 octave or 2:1.) Each of those octaves has its own character, and a great deal can be learned about audio and music by a detailed study of these octaves. Fig. 1 describes the 10 octaves in a fair amount of detail. Have fun!

A SIMPLER WAY

For our purposes here, we can start by thinking about the spectrum in a more basic three-part way: bass, midrange and treble. What could be simpler? These three regions all have their own functions, and if we control them well, we can really enhance the quality of our work.

Basically, bass refers to all the energy below about 200 Hz. This bass region provides richness, fullness, energy and body. Due to the physics of room acous-tics, loudspeaker variability and the quirky nature of our hearing, bass is also extremely variable and hard to work with and predict. In television broad-cast, except for the subwoofer channel, the bottom octave (20 to 40 Hz) can be dispensed with, and we can set bass by changing the level of the spec-trum from approximately 50 Hz to 250 Hz.

Fig. 1: The Ten Octaves of the Audio Spectrum, annotated (from “Total Recording,” KIQ Productions) Midrange refers to energy in the region from about 200 Hz to 2,000 Hz. The lower end of this range is sometimes referred to as the "mudrange" because of its tendency to add "muddiness" to the sound when injudiciously boosted. More importantly, the midrange covers an ambiguous spectral region in our hear-ing, wherein it "crosses over" from one mode of neurological detection of sound to another. The specifics of this are way beyond the scope of this column, but the perceptual ambiguity is real and it affects everything from perception of pitch to transparency to the perception of overtones. (What are overtones, you ask? Well, we'll talk about them next column.) For our purposes here, this midrange region is generally where we adjust the relationship between fullness and transparency. Boost the midrange to make the sound fuller. Cut the midrange to make it more transparent. Gently now, gently does it!

Treble refers to everything above about 2,000 Hz. (maybe a little lower than that—use your ears). Interestingly, this region includes no musical pitch fun-damentals (high C is 1,040 Hz), only overtones. Everything here is timbre tweaking… how bright, how brilliant, how edgy, how airy, and, most important for voice, how intelligible. Try gently boosting the region between 3,500 and 4,200 to make voice more intelligible. In television broadcast, we won't have much in the range over about 12 kHz, so the top octave isn't all that important.

THAT SUMS IT UP

In a simple sense, that's the audio spectrum. With equalizers, we manipulate the level of each of these regions independently in order to make the sound fuller and with more energy, while also more transparent, with brilliance and intelligibility. The equalizer is one of our most powerful tools, just because of this capability.

However, using it takes skill, practice, patience and some careful, critical listening. One of my very good colleagues worries that many producers and engi-neers in TV haven't developed the skills or ears yet to do it well, and should leave it alone, because it is quite possible to make a given sound much uglier with EQ as well as much more beautiful—in fact it's much easier to do ugly than beautiful.

My take is that you need to practice it, and practice listening to the effect of equalization. It will take a while, but it's worth the time and effort. Once you have it in your ears, you can do a lot, and it will seem like magic to your less skilled colleagues. Finally, remember, you are tweaking the spectrum: bass mid-range and treble.

Next column, I'll talk about how we actually approach the equalizer and make it work for us, for fun and profit.

Thanks for listening.

Dave Moulton is an audio guru, spreading information around like apple seeds. Somebody has to, right? You can complain to him about anything at his Web site, www.moultonlabs.com.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.