Hammering Out the Details of Internships

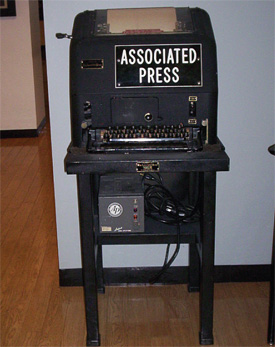

On my way to visit a friend's office the other day, I happened to walk past Seattle's The Associated Press office. Just inside the glass door was an ancient wire-service teletype machine, which was very state-of-the-art when I broke into the TV business. They've now been replaced by newsroom computers. That old machine reminded me of interns.

IN THE OLD DAYS

Back in the day we probably had three or four of those wire-service machines in the station's newsroom. They were walled off in a room of their own, with triple-pane glass to keep the clattering of the machines from driving the news staff crazy. There was a problem with that arrangement, however.

When an important story came across the wires, the machine typed BULLETIN in all caps, and I think it triple-spaced the breaking news text. Since that typing still just sounded like typing, to alert everyone it was a bulletin, a little bell on the machine rang.

The problem was no one outside the soundproof room could hear the bell. So we'd get a late start on a big, big story, and the news director would come unglued.

I remember one news director's solution was to put an intern in that wire-machine room to clear the news copy, tear the endless sheets of paper into sections for the sports guy, the weather man, the political reporter and so on. That's what they told the intern anyway… he was really there so somebody would hear that bell.

The Associated Press wire-service machine After a college student spent a quarter boxed up in the wire-machine room, I always wondered what they thought we did to him when he got back to school.

Internships seem to run the gamut from near slave-labor situations to a quarter of which work unsupervised and are given the run of the station.

At their worst, they can be a waste of time, both for the student and the station, and resented by station staff. At their best, internships can provide real-world working experience in television that rounds out an individual's education. (Or maybe tells him that TV is not the life for him.)

An internship can also provide a manager an extended look at a potential employee's work skills and work habits.

There's a long list of conditions that affect internships, conditions that vary from station to station, market to market. They include union rules; state wage and hour laws; company personnel policies; insurance considerations; the school's own rules on internships; your boss' druthers and so on. I'm going to ignore them as I write this, but in practice you can't.

THE BENEFITS

The best internship situations I've seen are the ones where quite a bit of groundwork has gone into the internship before the student shows up at that station. Whether the school approaches the station inquiring about an internship possibility, the station approaches the school, or the potential intern tries to broker a marriage between station and school, there are expectations and obligations on all three sides: station, school and intern.

From the school's standpoint, what can the intern expect to learn? The school can benefit doubly from a good internship experience for its students: their graduates will likely be better educated for having spent an internship at a station, and the student can bring back to the school some real-life experience that can teach the teachers. It's a good bet that it's been quite a few years since the professors worked at a television station, if they ever did. They can use a refresher.

From the intern's standpoint, it's not only what they can expect to learn, but what's expected of them? Who do they report to at the station? When are they expected to be there? If they are working to put themselves through school, can that job and the internship both fit together? Will the student be attending classes during the internship? Is it a paid internship? What are the rules, from both the school's and the station's standpoint? What is appropriate dress?

From your own standpoint, who's going to supervise the intern? How much of what the intern does is going to be, in fact, slave labor, and how much teaching is going to go on? What can you let them do? What does the school expect in the way of an evaluation of the intern at the end of the internship? Who's going to write that evaluation?

It's also a good idea to explain to your staff what's up with the intern before a stranger shows up.

The answers to these questions are good things to get down in writing before the internship starts. And I would formalize one more point: no matter if the past dozen interns have immediately been hired at the station, the internship does not guarantee a job.

Whether or not the intern works directly for you, it's a good idea to take them to lunch every few weeks or so to talk about how it's going. Being a starving student, they'll probably appreciate the meal as much as the conversation.

At some stations internship relationships with schools have been running for years, probably pre-date your arrival at the station and may well outlast you. If you'll excuse the double negative, it doesn't mean they can't be improved.

Craig Johnston is a Seattle-based Internet and multimedia producer with an extensive background in broadcast. He can be reached atcraig@craigjohnston.com.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.