Back to the Future

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

CHICO, CALIF.

The camera has taken the production world by storm in recent years for its high resolution, versatility and cost effectiveness. Now, the next event that marks the rise of the RED ONE is about to occur.

That happening will be the RED ONE's initial use in the PBS documentary "400 Years of the Telescope," slated to air on the network on April 10. And it could be the first science doc to be filmed in 4K, according to Kris Koenig, general partner of Interstellar Studios, which produced the series in conjunction with PBS.

"As far as we know, that's true," he said, adding that shooting with the RED ONE ensured that the doc will be accessible in whatever format is necessary for distribution—a big deal when the funding organization wants to maximize exposure for the program. The lead-in to the selection of the RED ONE for "Telescope" was its use in another Koenig project, "Two Small Pieces of Glass," a planetarium show that will be featured at more than 750 planetariums worldwide this year.

"When we went to shoot 'Telescope,' we were already set up," he said. Convenience was only part of the reason for using RED ONE, however.

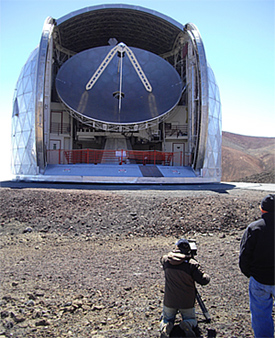

"For 'Telescope,' we traveled to five continents and to all of the major observatories in the world. Many are situated in scenic locales and we wanted to capture their grandeur," Koenig said. "Plus, the RED ONE enabled us to use a whole suite of Zeiss prime lenses to do just that."

Koenig and crew traveled the world for eight weeks to Europe, South Africa, Australia, Chile as well as the United States during production and "the RED ONE's resolution and versatility allowed us to return with the best product possible," he said. Yet, as obvious a choice that the RED ONE may have seemed to be for "Telescope," its use was not without risk.

"We took a chance here," Koenig said. "We took it to some tough, cold climates and even set what I believe is a world altitude record for its use" at 17,000 feet above sea level in Chile. "No matter where we went, from the 20-below temperatures at the Atacama Plateau in Chile to 65 degrees at sea level that same day, it performed beautifully," he said. "One hard drive was a little sketchy, but we used the Flash card and it performed great. This is a solid, solid camera."

TAKING EVERY AVENUE

As noted, the fact that Koenig could segue from delivering what is basically 35mm content for broadcast to SD Web transmission was key to this production.

"We have an obligation to the National Science Foundation, since it gave us a $1.2 million production grant, to get the doc into as many venues as possible," he said, noting international distribution plans include broadcast as well as film arenas. That means that the availability of the 35mm print for special screenings at science centers, museums and hopefully, the film festival circuit was critical.

"We also have a 2K file that will be used for certain digital theaters, SD and Web broadcast applications," Koenig said. "We want this to be seen by as many people as possible and the RED ONE took away any restrictions."

That's what it's all about to the Lake Forest, Calif.-based manufacturer. "Since [Koenig and company] produced a documentary about the history of the telescope, selecting a camera with super high resolution seems like a natural choice," said Ted Schilowitz of RED Digital Cinema. "Until recently, they might have elected to shoot the footage on 35mm, but now they have a viable choice with the RED ONE and what they have [acquired their content on] is essentially a digital version of 35mm film."

COST CUTTER

Kris Koenig, producer, shoots Galileo's telescope at the IMSS museum, Florence, Italy Not only was using the RED ONE successful from an aesthetic point of view, it made financial sense as well. Koenig said he "probably saved about 45 days of manpower during production because of the log and capture that would have been required otherwise. Plus the cost of tape would have run up to $150 per day."

The RED ONE helped Intellersteller acquire footage in a more efficient manner, Koenig added. "Because it's digital, [the content] goes straight from the hard drive on the camera to a laptop or to download at the studio for offline, so dailies are easy to screen and manipulate," he said. "We can even use the playback on the camera if we have a question about the content."

The next matter concerns post. "You're working with the raw image, which gives the editor greater latitude," Koenig said, "but production is ultimately about the product. And we delivered a better product using the RED One."

Interestingly, Koenig estimates that "99 percent of the people who shoot the RED ONE never totally utilize its 4K aspect, since the delivery product will come in at 2K or less due to post costs," he said. "Still, most producers shoot in 4K because doing so may eventually come in handy. This camera takes the user across the spectrum."

That any producer can deliver a program in any platform is mainly due to not being restricted by the manufacturer's lens and chip size. "We can use any PL mount prime lens combined with the latitude of a raw source file to create the look we want," Koenig said, "and deliver the final product as a 35mm print, 4K or 2K digital file or 1080p for broadcast and even SD—although SD is on the way out, except for Web-based platforms."

Interestingly, while the doc examines history, from a technological standpoint it's about the future, too. According to Schilowitz, there have likely been more than 500 feature projects, TV shows or documentaries shot on the RED ONE already, plus thousands of spots.

"There is still a viability for film," he said, "but there's a question of expense and complexity. With the RED ONE, you can achieve the quality of shooting film without the costs and complexities. So we've cracked that code a little bit."

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.